Last month, in an article for The Nation on “Why Hillary Clinton Doesn’t Deserve the Black Vote,” Michelle Alexander detailed the toxic consequences for black families and communities of President Bill Clinton’s 1994 criminalization bill and his 1996 welfare-to-workfare act—and the first lady’s vigorous lobbying for both pieces of legislation. Considering these bills alongside Hillary Clinton’s blithe description of black youth as “superpredators” in need of being brought “to heel,” Alexander concludes that the Clintons did not “courageously stand up to right-wing demagoguery about black communities,” as they have claimed. Neither did they “take extreme political risks to defend the rights of African Americans” nor “help usher in a new era of hope and prosperity for neighborhoods devastated by deindustrialization, globalization, and the disappearance of work.”

The title of Alexander’s article positions readers to anticipate a clear-eyed, full-throated endorsement of Bernie Sanders. Yet Alexander offers no such thing. “The biggest problem with Bernie,” Alexander writes, “is that he’s running as a Democrat—as a member of a political party that not only capitulated to right-wing demagoguery but is now owned and controlled by a relatively small number of millionaires and billionaires. . . . I am inclined to believe that it would be easier to build a new party than to save the Democratic Party from itself.”

To this end, the real power of Alexander’s critique is in using the Clintons as a lens through which to consider larger questions about the modern Democratic Party. Is it capable of offering a truly progressive political vision that reflects the needs of working women and men and aspirations of communities of color? Indeed, how did it move so far to the right?

One explanation sees the failures of today’s Democratic Party being sown in the 1980s. But narrating the ’80s as the Age of Reagan mistakenly suggests the left’s rightward turn was inevitable, and it obscures political battles that raged within the Democratic Party during that decade. Yes, Reagan and the Republican Party pulled the Democratic Party to the right, but at the same time Jesse Jackson and his National Rainbow Coalition were pulling the party to the left. We need to reckon with how the Democratic Party chose to deal with these competing pressures.

In 1983 Jesse Jackson announced his presidential platform in starkly multiracial terms:

This candidacy is not for blacks only. This is a national campaign growing out of the black experience and seen through the eyes of a black perspective—which is the experience and perspective of the rejected. Because of this experience, I can empathize with the plight of Appalachia because I have known poverty. I know the pain of anti-Semitism because I have felt the humiliation of discrimination. I know firsthand the shame of bread lines and the horror of hopelessness and despair. . .

Although Jackson lost the 1984 Democratic nomination to Walter Mondale, he managed to place third in the primary with more than 3 million votes. When Jackson ran again in 1988 he placed second, winning nearly 7 million votes and more than one thousand delegates—more than any runner-up in history, according to journalist JoAnn Wypijewski. Pulled between Reagan, Jackson, and an electorate that for five out of the previous six presidential election cycles had chosen a Republican, the Democratic Party was in crisis.

When the GOP won white voters by dog-whistling white supremacy, Democrats wooed them back with a renewed commitment to “mainstream America.”

To “solve” the Reagan-Jackson antinomy, centrist and conservative white Democrats from the South—led by political strategist Al From and including Georgia Senator Sam Nunn, Virginia Governor Chuck Robb, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton, and Tennessee Senator Al Gore—established the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) in 1985 with the chief aim of “mov[ing] the party—both in substance and perception—back into the mainstream of political life.”

The DLC repudiated Franklin D. Roosevelt’s development of the social welfare state through New Deal initiatives and what it perceived to be Lyndon B. Johnson’s partiality to special interest groups. No longer was the Democratic Party interested in speaking to, and representing, its core constituency since the 1960s: people of color, labor, women, the working poor, and the unemployed. Instead, the DLC couched its campaign rhetoric and policy platforms in the language of “mainstream America” and “the forgotten middle class.” The DLC was determined to make the party more palatable to the white men—especially the Southern white men—the Democratic Party had lost to the GOP after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other political victories won by people of color. If Nixon’s Southern strategy opened the GOP’s door to alienated white voters by dog-whistling an embrace of white supremacy, the DLC’s aspiration to move the party into the mainstream of political life was an attempt to court those same voters.

Though the DLC was established in 1985, it didn’t become a significant force within the Democratic Party until after Jackson’s second-place primary finish in 1988. At a DLC conference in November 1989, Louisiana Senator John Breaux told attendees that the party needed to redirect itself “toward a mainstream agenda” because “working-class white Democrats have been deserting the Democratic primary process in droves.” That same morning, Robb, now a senator, asserted:

Policies forged in the economic crisis of the 1930s and the social and cultural schisms of the 1960s are less and less relevant to the changes and challenges that are facing America domestically and internationally. . . . the national Democratic Party has in some important respects strayed from its historic mission of expanding opportunities for ordinary Americans. Instead, far too many Americans have come to believe that our party is more interested in expanding government for the benefit of special interests.

The Democratic Party had a choice: incorporate progressive “special interest” elements of Jackson’s National Rainbow Coalition platform—such as single-payer universal healthcare, living-wage policies, and alternatives to incarceration—or ingratiate itself to “ordinary Americans”—the white electorate—through scarcely hidden, racially encoded appeals to continued white political dominance. At the urging of the DLC, the Party chose the latter. Although the DLC officially closed its doors in 2011, many of its former members are now part of the Obama administration, and there is ample evidence that the DLC’s white-dominated racial legacy lives on within today’s Democratic Party.

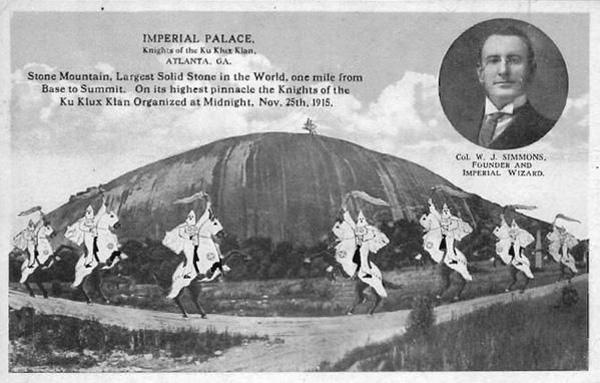

On March 1, 1992, just a week before Super Tuesday—itself a DLC invention to address the supposedly outsized role that “issue activist and interest group leaders” had come to play in the nomination process—the DLC held a Clinton campaign event at the Stone Mountain Correctional Institution in Stone Mountain, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta. The event took place in the months between Bill Clinton’s peregrination to Arkansas to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a black prisoner with documented intellectual disabilities, and his “Sister Souljah moment” in May, when he vocally distanced himself from Jackson and radical black activism.

A striking photograph from the Stone Mountain event, which Wypijewski describes as “the iconic image of ’92,” shows “Clinton and [DLC leader] Senator Sam Nunn posing at Stone Mountain, Georgia . . . and in the middle distance, a group of black prisoners.” Directly behind Clinton stands Georgia Governor Zell Miller, who made headlines in 2004 when he crossed party lines to support George W. Bush instead of John Kerry. Flanking Clinton opposite Nunn is Georgia Congressman Ben Lewis Jones, former star of The Dukes of Hazzard and outspoken defender of the Confederate flag.

Perhaps even more consequential than the photograph’s mise en scène is its location. Stone Mountain, is Georgia’s “most renowned historical marker,” as Somini Sengupta points out, and “one that many people would rather not remember.” The modern Ku Klux Klan was born in 1915 at a Stone Mountain rally celebrating President Woodrow Wilson’s White House screening of D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. Griffith’s movie, often credited as the first feature-length film, is a white supremacist hagiography narrating the Klan’s Reconstruction-era “protection” of white women from the uncontrolled sexual aggressions of free black men. For the next fifty years, Stone Mountain was the site of an annual Labor Day cross-burning ceremony. It is also home to the Confederate Memorial Carving (begun in 1923 but only completed in 1972), a Mt. Rushmore–style grotesquerie that depicts three leaders of the Confederacy: Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis.

It is hard to imagine the DLC would not have been aware of Stone Mountain’s significance as a theater of white supremacy when it staged Clinton’s campaign event at the prison there. In fact, the choice of that particular place as a campaign stop—arranging white political leaders in business suits in front of subjugated black male prisoners in jumpsuits—is illegible except in light of this history. One would be hard-pressed to find a photograph that more forcefully exposes the deep racial paradox of the DLC and the modern Democratic Party. Perhaps this helps to explain why Alexander holds “little hope that a political revolution will occur within the Democratic Party without a sustained outside movement forcing truly transformational change.”

Of course, white supremacy proliferates even more flagrantly within today’s Republican Party. White supremacy is not a party issue. It transcends such porous boundaries in order to remain ubiquitous yet unmarked. Indeed, part of what makes its endurance possible in the two-party electoral arena is that each party marshals the language, tropes, optics, politics, and policies of white supremacy in distinct ways. One party’s tepid attempts to “improve race relations” become visible only when juxtaposed against those of the other party. Whereas the modern Republican Party often seems disturbingly unwilling to critique even the most conspicuous forms of white supremacy, the Democratic Party seems eager to reach for “post-race” without giving serious attention to the historical production of race itself. The difference is more tactical than substantive.

Most problematic, however, is the near-total erasure from canonical history of watershed, critically symbolic events such as Clinton’s photo op at Stone Mountain—and what they reveal about the birth of the modern Democratic Party. Examination of this history unlocks the possibility of truthful public conversations about the harm done by the party’s rightward shift. It is a pre-requisite in moving the party back to the left.

This election cycle presents an opportunity to draw on the organizing potential of forceful, progressive grassroots movements such as Black Lives Matter and the Bernie Sanders campaign to demand that, this time around, the Democratic Party accept an invitation to move left. History doesn’t pass; it accumulates. Seizing the present as a historical moment requires policies that repair our nation’s collective racial and economic supremacies. Demanding that the Democratic Party confront its serrated legacy of white supremacy in the modern era—and its reflexive groveling at the jagged edges of capitalism—is but one of many steps toward creating a politics inclusive of those the party alleges to support.