In the 1790s an English baronet named Frederick Eden, concerned about the economy and the realities of the poor, went into the British countryside and began to collect data on the household budgets of poor agricultural laborers. He collected budgets himself, got additional data from “respectable clergymen,” and hired others to get even more. The results were published in the groundbreaking 1797 work, The State of the Poor. Eden had eighty-six families’ worth of data.

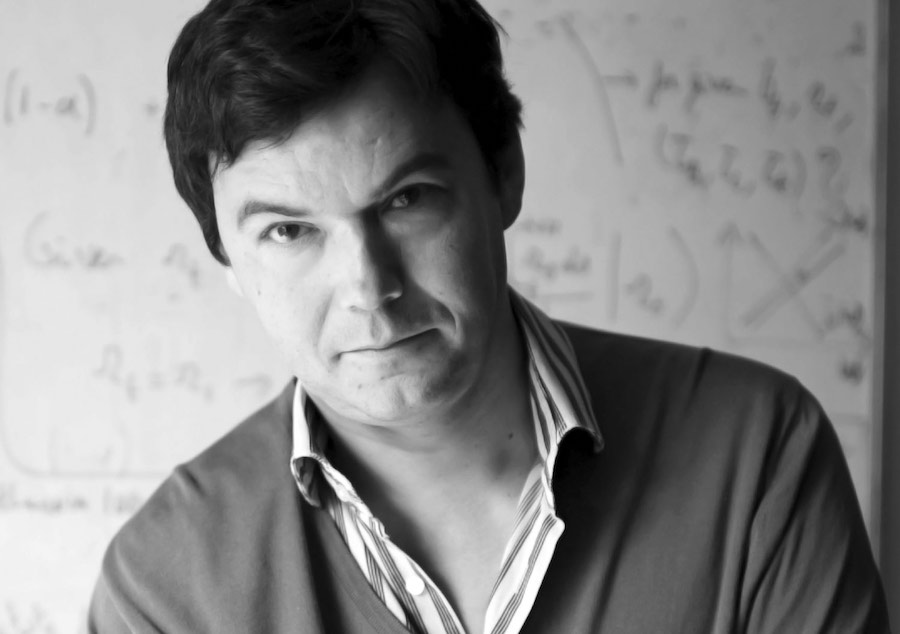

Meticulous as his study was, it would have been impossible for an early researcher such as Eden to assemble or comprehend the kind of data that underlies Thomas Piketty’s surprise bestseller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a great achievement of economic history. On any given page, there are figures about the total level of private capital and the percentage of income paid out to labor in England from the 1700s onward. Capital reflects decades of work gathering national income data across centuries, countries, and class, done in partnership with scholars across the globe.

Piketty’s book is also a refreshing departure from its peers. Recent popular economics books tend to simplify and reduce everything to pet theories, with the idea that incentives can explain everything. Capital does not read like these books. Piketty writes with a depth and seriousness that goes beyond such cleverness. His engagement with the rest of the social sciences also distinguishes him from most economists. Whether discussing the rate of population growth or the reasons that determine why people save, Piketty looks to cultural, historical, and psychological explanations alongside economic ones.

Beyond its remarkably rich, sophisticated, and instructive history, the book’s novel engagement with inequality has drawn well-deserved attention and criticism. By considering the initial debate over the book, we can examine what is at stake in how Capital is understood.

The Stakes and the Dominoes

Piketty’s book warns that capital and inequality are likely to make even greater strides in the next few decades. The influence of wealth and inheritance could make our economy look a lot like that of the nineteenth century, with more of its dominant dynastic fortunes and less of the joint prosperity we have come to assume is the natural state of advanced economies. This is a grim prediction, and Piketty supports it with what he sees as two fundamental laws of capitalism. Instead of walking through these equations, it is easier to picture his argument as a series of three falling dominoes.

The first domino falls because the rate at which the economy grows (g), as a result of both productivity and population increases, is less than the rate of return on capital (r). This is the much-discussed “r > g” formula, which Piketty describes as the central contradiction of capitalism and the “principal destabilizing force” that yields stark class inequalities between owners of capital and others. As Piketty shows, this inequality has held for most of human history, with the exception of a brief period in the twentieth century. And as economic growth slows in the next few decades, if only as a result of decelerating population growth, the differential will be even greater.

With economic growth on the wane, the second domino falls: the amount of capital relative to a country’s income goes up. This takes time, but eventually it will lead to an even larger capital stock compared to the economy as a whole. Consider the historical trend: in the late nineteenth century, the value of capital was five times that of world income. The multiplier fell to less than three during the 1950s, but has now returned to those previous levels and continues to increase.

The mantra that a rising tide lifts all boats has been dealt a fatal blow.

Why does it matter? First, capital ownership is concentrated. In the United States, the top 1 percent of wealth holders owns 35 percent of all capital, and the top 10 percent owns roughly 70 percent of capital. The bottom 50 percent has roughly 5 percent of capital. Piketty argues that “the past tends to devour the future”—wealth accumulated in the past becomes more dominant and commands more power and attention than wealth being created now. In France, for example, where the inheritance data is best, the wealth of the dead amounts to nearly twice that of the living.

As the amount of capital balloons relative to the size of the economy, the third domino falls. And if the rate of return on capital, r, doesn’t drop precipitously, capital will continue to take home an even greater share of the economic pie. Indeed capital’s share of U.S. national income has been increasing in recent years, from the low to high twenties, percentage-wise. Piketty’s projections show that, in the long run, this rate could rise to between 30 and 40 percent, placing it much closer to that which prevailed at the end of the nineteenth century.

Economists used to assume that the share of the economy taken home by capital and labor was relatively stable. This stylized fact was discovered in the 1950s and embodied the postwar optimism that capitalism could ensure prosperity for workers and elites alike. But, in fact, the fixed relationship between capital and labor in the 1950s was an anomaly. The enormous destruction associated with two world wars and the Great Depression had reset the dominoes and allowed for mass prosperity in the postwar period. Piketty argues that the dominoes are starting to fall again.

Piketty’s case is persuasive and well supported. So what is the debate over? Much of the critical response to Capital has focused on Piketty’s r > g formula and what the rate of return on capital is doing in Piketty’s story. Generally, critics have come at him from two different directions. Though these debates aren’t necessarily ideological, the directions tend to be associated with the right and the left respectively.

Countering Critics

Economists tend to build tight stories and models and then look outward at the data that may or may not fit. Piketty, on the other hand, starts with the data and then looks at various models economists have deployed to see which, if any, fit. A useful example is the life-cycle theory of consumption, created in the 1950s by the economist Franco Modigliani. In this model, the primary role of savings is to finance retirement. Piketty takes an extra step to point out that this model was developed at exactly the moment when the value of inheritance was at the deepest point of its historical ebb. He puts the model next to the data and concludes it doesn’t tell us much. It is a rare move for an economist, and the book is filled with brilliant moments like it: Piketty shows how economists often reflect the society around them when they create supposedly ahistorical or apolitical models.

But by not locking his own argument tightly to a model, he also leaves himself vulnerable to criticism that there are trends toward equality he misses. Notably, some critical reviews, in both general and technical terms, have argued that the third domino is unlikely to fall. The more capital there is, the less productive it will be at the margins, so the rate of return should decrease. If it decreases rapidly, capital’s share of national income will not rise. Though the past will still suffocate the present when it comes to wealth, the full-blown crisis—where capital consumes more and more of what we create—can be avoided. This criticism is more common on the right, but not solely of it. As Lawrence Summers argues in Democracy, “Economists universally believe in the law of diminishing returns. As capital accumulates, the incremental return on an additional unit of capital declines.”

Since the book’s publication, some economists, such as Brad DeLong, have put this argument into a more formal model. And positive reviewers, such as Robert Solow, have been careful to observe that though the returns on capital might fall, the effects won’t be large enough to prevent capital’s share from rising. As Seth Ackerman noted in a favorable review, Piketty is able to avoid some of the straitjacketing that comes with the formal models of economics by focusing on wealth inequality, which is less studied terrain. But this argument from diminishing returns is likely to dominate the reaction of economists going forward.

Piketty counters that, to whatever extent this happens, the substitution rates he believes are in effect ensure that the fall in the returns to capital won’t happen fast enough. Indeed, his evidence not only tracks the dominoes falling historically but suggests that they are already falling again. Irrespective of the theory, in practice, the dominoes are falling.

Piketty’s empirical evidence has stood up to critical scrutiny so far. One set of criticisms, from Chris Giles of the Financial Times, fell apart once Piketty had a chance to respond. Giles argued that wealth inequality hasn’t increased in recent decades. Piketty, in a devastating response, argued that the FT was only able to say this by combining two disparate data sets in an apples-to-oranges comparison. In fact a major subsequent study, using even better data, found that wealth inequality is increasing faster in the United States in recent decades than was previously understood.

Another interesting criticism, from National Review, is that Piketty doesn’t try to ground his normative concerns about inequality in strictly economic terms or a model that predicts “the optimal level of inequality.” And that is true. Although Piketty does reference John Rawls’s idea that just inequalities are those that work to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, he doesn’t try to establish an optimal amount of inequality.

But that isn’t his goal. The book is an attempt to ground the debate over inequality in strong empirical data, put the question of distribution back into economics, and open the debate not just to the social sciences but to regular people. As Piketty says, the distribution of wealth “is too important an issue to be left to economists, sociologists, historians, and philosophers. It is of interest to everyone, and that is a good thing.”

Institutions of Politics and Power

If critics to Piketty’s right are concerned that he doesn’t ground his theory deeply enough in economic models, economists and others to Piketty’s left are concerned that he concedes too much to mainstream economics and lacks sufficient regard for politics.

Recently the left has been emphasizing the way the state, through law, regulation, and public policy, necessarily structures markets. In this telling there is no such thing as a “free” market, just different choices about how to structure markets fundamentally based in politics and power. The idea of a free market is a vacuous, question-begging abstraction, invoked to defend the status quo or the interests of the wealthy. A quick look at the titles of current academic works such as The Illusion of Free Markets, The Myth of Ownership, and The Progressive Assault on Laissez Faire gives a sense of the argument.

This context explains what is at stake in the left critique of Piketty. Some economists, such as Dean Baker, have argued that Piketty doesn’t do enough to explain how regulations of property, patents, and finance could help deal with the problems he identifies. Others, such as James Galbraith, invoke debates among mid-century Keynesians to argue that adding up capital and assigning it a return doesn’t make sense as a model. More broadly, Piketty has been criticized for not acknowledging how institutions and politics influence the returns on capital: his domino theory is too focused on economic forces.

So while economists to Piketty’s right think he should create a model that predicts the rate of return on capital (his r) based on the state of the economy rather than on historical data, economists to Piketty’s left want him to emphasize the idea that many different rates of return are consistent with the character of the economy: r is a function of institutions and political decisions. Those on the left also worry that the debate over Capital could devolve into, as the economist Suresh Naidu argues, a “bastard Pikettyism” that just navel-gazes at the mathematical economic models discussed above instead of a broader, more critical inquiry into how capital works in economies and societies.

It is true that Piketty doesn’t clearly state the role institutions and political action are meant to play in his theory of the evolution of inequality. Nonetheless, scattered throughout the book are clear signs that he is thinking about the institutional arrangements that can influence the return on capital.

Piketty writes:

It is important to stress that the price of capital . . . is always in part a social and political construct: it reflects each society’s notion of property and depends on the many policies and institutions that regulate relations among different social groups, and especially between those who own capital and those who do not.

An obvious and extreme example of what Piketty has in mind is the class of human beings who were part of the capital stock under slavery in the South. Once that system of property was destroyed, they were no longer part of capital.

And he argues that the labor market “is a social construct based on specific rules and compromises,” where the minimum wage and social norms play as large a role as do skills and education. He also finds that the 1950s had an even lower level of capital accumulation than expected because real estate and stock prices were themselves low, partially as a result of rent control and tighter financial regulation.

In a telling example, Piketty notes how his theory doesn’t work when he uses stock market valuations for German companies. But it does work when he uses the book value, or the value of the individual investments of each firm. Why? Because under the German “stakeholder model,” more of a firm’s economic value is kept in house, instead of being distributed to those who own company stock.

Economists to Piketty’s left think he doesn’t concede enough to politics.

These passages surely suggest that Piketty believes that r is not a fixed economic parameter and that, as a political project, something can be done about r. Why doesn’t Piketty embrace this idea, or at least make more of it in his theory?

The answer is partially driven by the numbers. If r is consistent across countries and centuries with radically different infrastructures, institutions, philosophies, and populations, structural and institutional changes are unlikely to make a big difference. Piketty emphasizes that the trends he finds are not the result of the various “market imperfections” that economists break out to justify government action. If anything, he argues, a more efficient market could increase the rate of return on capital and accelerate inequality.

Though he equivocates on this point, the text suggests that Piketty believes social democratic reforms outside high taxation are incapable of changing these dynamics. Though he spends an interesting chapter discussing it, he assigns no role in combating r > g to the growth of the social state that ensures access to health, education, and income security. Labor unions and the regulatory state are missing or underdeveloped in his analysis. Though those are essential to a more just society, Piketty ultimately thinks that not they but the wars, the Great Depression, and the high progressive taxation that resulted from war mobilization are what challenged and changed the dynamics of inequality.

In a revealing passage on French rentiers at the turn of the last century, Piketty writes, “Universal suffrage and the end of property qualifications for voting . . . ended the legal domination of politics by the wealthy. But it did not abolish the economic forces capable of producing a society of rentiers.”

This is a remarkable provocation for liberals. Piketty is, in a way, saying: go ahead and make whatever reforms you want. Break up the banks. Pass the campaign finance package of your dreams. Reach deep into the bag and pass all the reforms you can think of. They can’t guarantee that you are safe from the logic of r > g. Reforms won’t change the nature of capital: to accumulate, eat up a larger share of the economy, and subordinate the future to the past. What then?

The Gaze of Social Science

While Arthur Goldhammer’s translation of Capital from the French reads excellently, the only thing that arguably gets lost in moving the text from France to the United States is Piketty’s solution—the “useful utopia” of a global wealth tax. Piketty strongly hints that the proposed tax is directed at the European Union, noting that large countries such as the United States and China have their own ability to act through means that small, interconnected countries cannot.

Policies evolve from identifying a problem. Whether or not it is feasible, Piketty’s suggestion for a global wealth tax evolves from identifying the problem as global and systemic. And here this book signals a major change in the debate over inequality.

First, the rosy picture that economists have painted about the nature of inequality has been displaced. The idea that labor’s share of the economy is more or less fixed, an essential element of the mantra that a rising tide lifts all boats, has been dealt a serious, if not fatal, blow.

The idea that inequality is necessary for a well-functioning society has also been thrown into question. In the wake of the financial crisis and Great Recession, more and more researchers are finding that higher equality corresponds to higher growth, or at least has no negative effect. The causation here might be difficult to prove, but the studies suggest that we can no longer take for granted that growing inequality is a necessary evil for a better economy.

Second, the debate over wealth and taxes is back. Many economists argue that capital income shouldn’t be taxed at all, since it is unfair to tax people because they happen to save, as if it is simply a choice in the marketplace. There are, however, significant advantages to owning wealth, including security, political power, the ability to direct private investment, and much more. These benefits ought to be subject to democratic scrutiny.

Tax policy needs to go beyond raising revenues. Capital argues that high taxes can direct income toward more productive and less economically harmful uses, such as keeping incomes within a firm rather than enriching executives and managers. Inheritance taxes can help direct large fortunes toward use for the public good. In Piketty’s analysis, the decline of high marginal tax rates is the main culprit in the large growth of inequality internationally since the 1980s. Since this major transfer of resources didn’t cause an increase in economic productivity, the cost of undoing it will be minimal for the economy as a whole.

Whether more Democrats can speak this language will be a major test of the political momentum behind Piketty’s argument. Recall that during the fiscal cliff showdown, Democrats debated only where to set the highest marginal income tax rate as a matter of labor income. The possibility of increasing inheritance or capital gains taxes to old levels, or higher, was not on the table. As a start, David Brooks is already saying that the center and the right should respond to Piketty with a beefed-up inheritance tax.

But there is a bigger issue at stake here. Back in the 1790s when Frederick Eden was trying to understand the economy, he went and observed the poor. His small data set was enough for him to conclude that England’s system of relief was “the parent of idleness and improvidence.” His techniques were deployed during the nineteenth century to observe workers when socialist unrest began across Europe. As the historian Alice O’Connor has noted, this “poverty knowledge” industry persisted throughout the twentieth century, offering various explanations for how and why the poor were poor.

As Foucault argued, the ability of social science to know something is the ability to anthropologize it, a power to define it. As such, it becomes a problem to be solved, a question needing an answer, something to be put on a grid of intelligibility. A domain of expertise exerts power over what it studies.

With Piketty’s Capital, this process is being extended to the rich and the elite. Understanding how the elite become what they are, and how their wealth perpetuates itself, is now a hot topic of scientific inquiry.

Many have tried to figure out why the rich are freaking out these days. Their wealth was saved from the financial panic, they are having an excellent recovery, and they are poised to reap even greater gains going forward. But perhaps they are noticing that the dominant narratives about their role in society—avatars of success, job creators for the common good, innovators for social betterment, problem-solving philanthropists—are being replaced with a social science narrative in which they are a problem to be studied. They are still in control, but they are right to be worried.

Editors’ Note: This article was altered and updated for our July/August 2014 issue.