I met Renard in an unadorned room in a Catholic Charities building in New Orleans. Twenty years old, with a broad smile under chubby cheeks dotted with freckles, Renard is one of two dozen or so men and women who gather there regularly for Cornerstone Builders, a small Americorps program that provides community services jobs and training to ex-offenders. A few weeks before we spoke, Renard was released from prison where he was serving time for possession of marijuana and a firearm; he is still under correctional supervision. “They givin’ you ten years to mess up,” he says. In addition to the two and a half years in prison, he must complete two and a half years of parole and, after that, five years of probation.

Renard doesn’t think about the government in the way you or I might. Lots of Americans worry about too much government or too little. For Renard, there is both too much and too little. Until Cornerstone Builders came around, government had always been absent when he needed help, but ever-present otherwise.

“The government is hard,” he told me. “We’re free but we’re not free.”

Xavier, a long-time friend of Renard’s who joins him at Cornerstone Builders, has never been given a prison sentence but nonetheless described a life hemmed in by police and jails. Diagramming with saltshakers on the table, he showed me how a police station, courthouse, and jail encircled his neighborhood. Most of his family and friends have had contact with the criminal justice system, which he calls the “only government I know.”

When you meet people such as Renard, you see the human face of a system of punishment and surveillance that has expanded dramatically over the past fifty years. At this point, the facts of mass incarceration are well known. Families have been separated from fathers, sent away in greater numbers, for longer terms of imprisonment, seemingly without regard to the nature of their offenses. Millions have been economically and politically paralyzed by criminal records, which stymie their efforts to secure jobs and cast ballots.

But there is more to criminal justice than prisons and convictions and background checks.

Most people stopped by police are not arrested, and most of those who are arrested are not convicted of anything. Of those who are, felons are the smallest group, and, of those, many are non-serious offenders. In some cities, the majority of those who encounter criminal justice have never been found guilty of a serious crime, or any crime, in a court of law. Based on research in several cities across the country, my colleagues and I estimate that only three out of every two hundred people who come into contact with criminal justice authorities are ultimately convicted of violent crimes.

Criminal justice is therefore an institution far larger than the prison. It is a distinctive system of governance that trains people for a distinctive and lesser kind of citizenship. It exposes them to antidemocratic practices and teaches them that the state is not there to provide for the common good but to keep them in line. Their best strategy is to remain invisible.

• • •

The Divorce of Policing from Crime

Most people assume that those who have encounters with police, courts, and prisons do so because they are violent, dangerous, or behaving fraudulently—because they have seriously flouted the law. But this is not so. Criminal justice encounters are not confined primarily to offenders, and prison is not reserved primarily for serious offenders. Contact with criminal justice over the past several decades has been decoupled from criminal behavior.

One reason for this decoupling is that police today enjoy wide discretion over whom to stop, question, and pat down. Records from New York, where pat downs have been particularly controversial, reveal that police mostly stop and frisk people based on the clothes they are wearing, whether they pass through high-crime areas, and their “furtive movements.” Given such loose justifications, it is unsurprising that only 12 percent of stops in New York yield an arrest, citation, or summons.

Since the rise of “broken windows” policing—cracking down on loitering, trespassing, and public order offenses—in the 1980s and ’90s, officers have been making more misdemeanor arrests, which lead to easy convictions. The legal scholar Alexandra Natapoff has shown that these minor cases tend to follow a routine. Despite the thin merits of many order-maintenance arrests, prosecutors file charges in nearly 100 percent of cases. There is little incentive not to: such cases cost little to prosecute and almost never go to trial, and because they have lower evidentiary standards than more serious charges, the state almost always wins. Whether or not the defendant is guilty, prosecutors know they can extract a plea because the pressures of bail, waiting in jail for the case to get to court, and the risk of conviction for a heavier charge make pleading in exchange for lower penalties attractive. Without guaranteed counsel—public defenders are only required when a conviction could result in jail time, which is usually not the case on a misdemeanor charge—defendants accept more than 90 percent of plea bargains. Thus police decisions about whom to arrest—not evidence of guilt—translate rather precisely into who ends up convicted. Crucially, taking a plea, even if one has broken no law, means accepting a criminal record, the consequences of which can be more onerous than a judge’s sentence.

“Misdemeanor justice,” combined with nonviolent offenders who have faced steepening penalties for failure to pay child support, committing technical violations of parole, smoking marijuana in public, and other small-time malfeasances, ensures that the majority of people who encounter the criminal justice system are low-level offenders.

What all this means is that the strong arm of the state is rarely deployed according to the seriousness of one or another violation. Imagine a coordinate graph broken into four quadrants. On the vertical axis is contact with criminal justice—being arrested, convicted, or incarcerated. On the horizontal axis is self-reported criminality. In a fair criminal justice system, we would expect most people to fall along the diagonal: those who have experienced criminal justice contact have done something illegal, and those who have not also have not run afoul of the law.

But in our system, a large group of young adults does not report any criminal behaviors yet has involuntarily been exposed to criminal justice. Based two cohorts of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, in 1980, this group was just 1 percent of 18–23 year olds. By 2002, the number had grown to 13 percent.

For decades, contact with criminal justice has been decoupled from wrongdoing.

While the criminal justice system has increasingly ensnared certain groups of non-offenders, it has ignored violations elsewhere. Most people, as the brilliant campaign We Are All Criminals reminds us, have committed an act, sometimes serious, that could have landed them on the other side of the law. But selection for arrest, not law-abidingness, has become the primary determinant of outcomes in criminal justice.

Add race and class into the exercise, and we see more evidence that the system has run aground. The same cohort analysis reveals that since the late 1970s, blacks increasingly moved into the contact/no offense quadrant and whites moved into the no contact/offense quadrant.

If conventional wisdom is quick to assume people who have disobeyed the law are the ones being frisked and put away, the institutions of criminal justice reinforce these assumptions. A prison I visited in Trenton, New Jersey is typical. Lining the walls of each corridor are signs reaching from floor to ceiling reading, in bold green lettering, “Make better choices” and “Learn from your mistakes.” These signs, along with parole requirements and mandatory restitution and counseling, communicate to inmates that America hasn’t failed them; they have failed themselves. They are authors of their fates, solely responsible for bad choices, and should accept responsibility.

And yet, according to most we spoke to, they had no choice. Among those living under the discretion of law enforcement, missteps are inevitable. The people we interviewed hailed from communities where job opportunities were scarce and drug markets flourished, where schools graduated few, and where youth were socialized not for success but for survival. Penal facilities also reinforce the message that, for inmates, criminal justice was always a likely stop on the way to becoming adults. According to Trevor, one of the prisoners I spoke to, once inmates were released, guards would send them off saying, “See you when you get back!” Compared to the exaggerated messages of individual agency in the signs, the guards are saying something closer to the truth: that convicts are in fact powerless, that the system can, in the words of one of our interviewees, “just grab you, just on its own.”

• • •

Antidemocratic Justice

While the connection between criminality and contact with the justice system has been unraveling, the institutions of that system have been tightening up.

In many ways, prisons and police stations do better than their pre-1960s variants, where coerced confessions, floggings, and fabricated evidence were commonplace. In the wake of a procedural rights revolution and prisoner rights movement, the justice system became fairer and more humane. But if we judge prisons, courts, police, and parole boards by how they reflect the commitments and principles of a democracy, their failures have mounted.

Democratic institutions allow citizens to voice their opinions and receive fair and equal responses, to have a say over who represents them and how, and to contribute meaningfully to the institutions that govern them. Democratic institutions are accountable.

Criminal justice institutions subvert these democratic norms. They undermine equality, offer few channels for association or the expression of grievances, provide few checks on the discretion of officials wielding enormous power, and are mostly unaccountable to their wards and to the wider public.

Under the Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1996, which largely removed inmates’ access to the courts, few inmates can challenge egregious violations of human rights behind the walls. Subjects of police overreach also face procedural hurdles. In an especially perverse case, Adolph Lyons, a black man who had been subjected to a chokehold by Los Angeles police during a traffic stop, sued unsuccessfully to end the practice, which had caused at least sixteen deaths in the eight-year period leading up to the suit. The Supreme Court ruled he didn’t have standing to sue unless he could show that he would be a victim of another police chokehold in the future.

Expansions in police and prosecutorial immunity have made suspects and convicts, in the words of legal scholars Michael Mushlin and Naomi Roslyn Galtz, “walking rights-free zones.” Meanwhile, prisoners face serious limits on democratic voice: prison newspapers, interviews with the media, and prison-based organizations, including unions, are heavily restricted. And ex-offenders often lose the rights to vote and serve on juries. None of these policies enhances the goals of crime control.

The result is that institutions that have become procedurally fairer and more humane in some respects continue to be experienced as antidemocratic.

These two features of the criminal justice system—the decoupling of criminality and exposure to control, and the antidemocratic character of institutions—are concerning in isolation. Together they have grave consequences for citizenship.

• • •

Custodial Citizenship

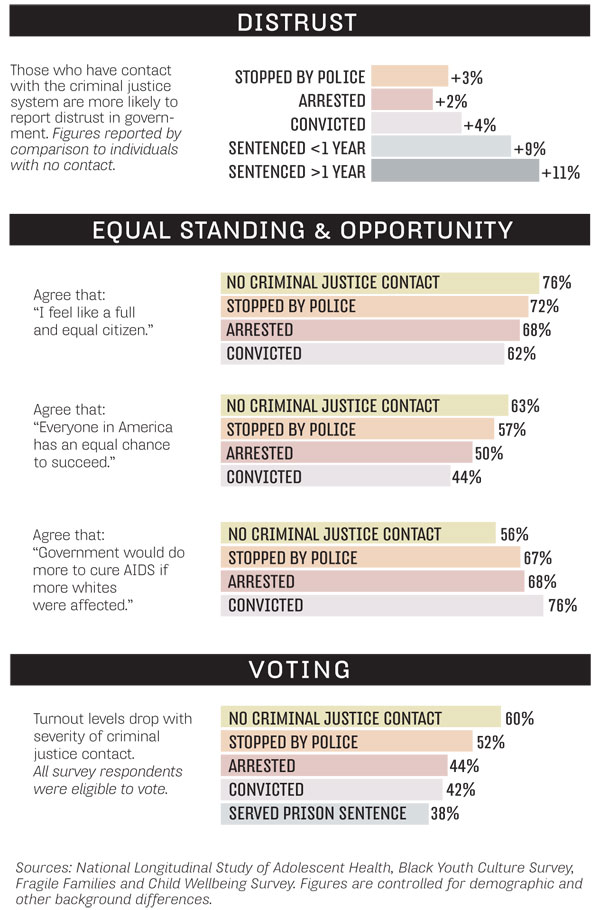

Criminal justice interventions transform how people understand their government, their status in the democratic community, and their civic habits—in a word, their citizenship. By analyzing several large, representative social surveys, my colleagues and I found that those who have been exposed to criminal justice tend to have low levels of trust in politicians and public institutions and a diminished sense of standing. They don’t believe the state will respond to their needs. Such people do not think they have an equal chance to succeed and see themselves having little influence over political decisions that affect them. One survey of youth and young adults asked whether “leaders in government care very little about people like me.” Among youth who had not had contact with the criminal justice system, 36 percent agreed. Among those who had been convicted of a crime, three-quarters agreed.

Civic engagement is the root democratic life, but the typical citizen of the custodial state stays low, out of sight. And felon disenfranchisement is not the only source of political withdrawal.

Many Americans shun civic engagement, but what sets custodial citizens apart from the merely apathetic or jaded is their preference for avoiding the state entirely. They believe that to do otherwise, to attempt to make a claim on the state, would be dangerous. Their relationship to the state looks more like that of an undocumented person than that of a citizen.

Take Bert, a middle-aged black man we met in Charlottesville, Virginia who had just been released from prison, where he served a five-year term for dealing cocaine. He describes government in one word: control. Like so many black men, Bert first encountered criminal justice as a boy, when he was sent to a juvenile home for truancy. Later, he faced difficulty paying off debts and child support, which led him to deal cocaine even though he had a job. Now he struggles with legal and “inmate user fees”—costs incurred from room and board, laundry, health care, and other prison “services”—so he finds ample reason to steer clear of government. “I try to stay away,” he told me. “I’m trying to avoid . . . even going down [to the court building] and paying fines. I got fines I have to pay and I don’t even want to go down there. I find a way of mailing it to ’em, talkin’ over the phone because I don’t really want to be around them. Talking to them, personally . . . it just makes me feel like if I stay in [there] long enough, they might find something else on me to lock me up for.”

Bert and the eighty-five others we interviewed in New Orleans, Trenton, and Charlottesville described long waits for their veteran’s benefits and police who refused to respond to calls on their street. But few pressed their claims. Marcus, who lives in transitional housing in Trenton and is serving out a lengthy parole term, spoke to me at length about the difficulty of finding a job and accessing his disability benefits. He contemplated submitting an official complaint but reconsidered. “I don’t wanna make things worse than it already is,” he said. Adele, a white woman in Charlottesville, explained that most people with past involvement with the system were “afraid of what’s going to come down on them.” Nora, an older black woman from Trenton, would not confront what she called a “housing issue” because she was fearful of what “they might say or do . . . tell me to get out, call security or something.”

In research focused on New York, my colleagues and I found that residents of heavily policed neighborhoods where police frequently used force on suspects who were not arrested made fewer calls to local government to report infrastructure problems such as potholes and broken streetlights.

In particular, citizens who wish to remain invisible give the police a free pass. Xavier, who has never been convicted of a crime but has nonetheless spent many nights on the cold floor of Saint Tammany Parish Jail and had countless encounters with police, described an incident when an officer jumped on him while he was sitting on cousin’s porch. But he decided not to lodge a formal complaint. “Nobody wants to put up the force to go fight against them because in the end, you know you’re going to lose!” he said. “If the police is seeing that you’re trying to fight them, they’re going to make it worse. They harass you. They’re going to try to lock you up . . . then once you in that jail cell, they can treat you however they want and they’re going to get payback. Cause you in here now, we going to handle you.”

In heavily policed communities, criminal justice is the only government people know.

The other side of this equation is that, when law enforcement and criminal justice officials need the cooperation of victims, witnesses, and jurors from heavily policed neighborhoods, they rarely get it.

Citizens of the custodial state learn early on that they need to take special pains to keep the police at bay. They learn never to be “out of place” in white neighborhoods, to avoid certain styles of dress, and to get a bag and a receipt whenever they shop. They learn to stay in at certain times of day: “If you’re on the streets between 7:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. and you haven’t got no job, you’re [assumed to be] selling drugs,” Xavier explained. They learn not to have guests to their homes “because if you have so much company coming, they automatically think you dealin’ drugs,” said Felisha, Bert’s girlfriend.

But they also know that precautions are futile. “It’s like they’re hunting tigers or something. Or lions,” Xavier said. “If you get to know me, I’m the funniest person. But me, I’m black. I got a mouthful of gold, tattoos on me. I’m already looking like a drug dealer.” Bert, Xavier, and the others we interviewed come from similar neighborhoods where police substations are commonplace and bookstores advertise shipping to prisons. Patrice, a Charlottesville teenager, told me that every member of her family “on both sides” had been fingerprinted—except her, a designation she was proud of. The men and women I spoke to often pointed out that almost all of their neighbors, friends, family, and church members had a record. Many said they had been stopped by police in just the last few days.

These people remind us that citizenship is not only about formal standing and rights; it is also about the ways in which citizens are socialized. By inhibiting the development of civic skills, diverting citizens from having a say in their government, and informing them that they are not worthy of equal concern and respect, criminal justice has transformed the experience of citizenship in America today. American criminal justice over the past half century—its growth to encompass a larger proportion of citizens many of whom are non-serious offenders, its persistent racial demography, and its decreasingly democratic character—has created a large and growing group for whom government is not a realization of democratic ideals but instead a source of control. Among those who feel they have no standing in the democratic community, dealings with government are to be avoided. More than simply punishing deviance, the American criminal justice system has created custodial citizenship.

Reversing the damage caused by our criminal justice system will take more than voter drives and renewed franchise for the nearly six million citizens whose records bar them from participating in the democratic process. Even then, among citizens such as Renard, Xavier, and Bert, avoiding the state will be a normal and necessary part of life. Demonstrations of their unequal worth will still be pervasive in their communities.

Criminal justice policy will continue to create invisible, custodial citizens until it is fundamentally reformed in three ways.

First, we need to tighten the relationship between criminal justice contact and serious offending. Our system selects for surveillance and punishment according to demographic categories rather than behavior. The solution here is not to widen the scope of police action to include middle-class suburban youths who engage in low-level drug violations—doing so would create political outrage and would require that we double down on investments in antidemocratic institutions—but to reduce surveillance of non-offenders and non-serious offenders.

Thanks to the ruling last fall in Floyd v. City of New York, in which the judge held that police were stopping and searching individuals in a racially discriminatory manner, the nation’s largest city will now have to report to an independent federal monitor, and police stops will likely decline in number. Other cities could follow suit. Curtailing law enforcement focus on low-level offenses would also reduce the share of people needlessly under surveillance.

Second, criminal justice institutions will always limit freedom, but they do not have to be antidemocratic in the pursuit of public safety. Thus, we need not only to scale back criminal justice contacts but to reinstate democratic practices, incorporating in the justice system democratic principles that govern other key American institutions: voice, accountability, and equality.

Consider how we would respond if our nation’s other governing institutions refused to provide the media even minimal access to their operations, gave blanket immunity to officials who had engaged in misconduct or coercion, and insisted on handling all claims of abuse in house. Criminal justice institutions engage in all of these practices, even as their powers are more totalizing, and their actions more discretionary, than perhaps any other governing institution in America.

How do we inject democracy—by definition open and participatory—into a closed system whose mission is to limit and confine? It is not really so hard; we have done it before, and other countries do it today. The first step is to require every state criminal justice agency to create independent oversight bodies that open their systems’ operations to outside scrutiny. Many nations have a central prison ombudsman. The second step is to amplify the voices of those subject to police contact. At the very least, people mistreated by police and guards should not have to hand their grievances to the agencies that mistreat them. More capaciously, this would mean incorporating mechanisms for voice and input within the walls, lifting restrictions on prison newspapers, civic groups, and voting—all things that would prepare inmates for active citizenship when they return to society.

Democracy thrives on popular perception of its legitimacy. Currently, the racial inflection of the criminal justice system undermines this legitimacy. Several reforms would go far here. Drug-free school zones, which blanket urban areas and lead to more severe punishments for those caught in them, and mandatory minimum sentences for non-serious drug felonies should be eliminated. The weight of a prior record in sentencing decisions should be reduced, in line with international norms. Sentencing and crime control policies that govern how we police and confine should be evaluated for their effects on blacks and Latinos before they are put into law, as they are in Connecticut, Iowa, Minnesota, and Oregon where racial impact statements are standard practice.

Finally more needs to be done to promote viable economies in poor, segregated neighborhoods. Justice reinvestment, which is being pursued at the state and federal levels, is one good approach here. It would reduce incarceration while simultaneously counteracting the conditions of poverty that lead to concentrated imprisonment in the first place. Basically, justice reinvestment calculates the savings to the state from reduced incarceration and plows those savings into community services, job training, redevelopment of abandoned property, parks rehabilitation, and affordable housing.

For decades, our nation has punished crime instead of protecting citizens from it; while overall crime rates have fallen, levels of victimization are catastrophically high among the communities most heavily policed and punished. This is not how democratic governments function, nor how democratic citizenship is fostered. For now, criminal justice is the only government Xavier knows. Without significant reform, his children will know no different.