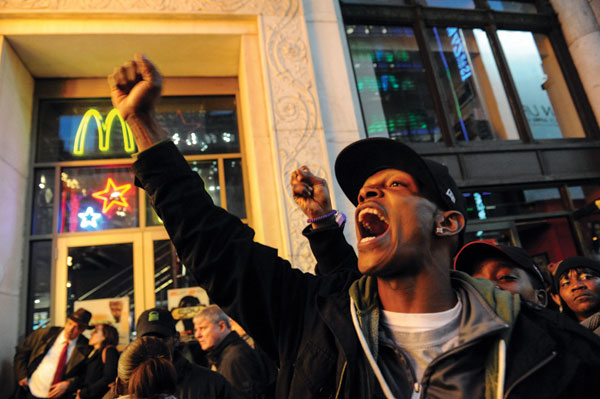

The minimum wage debate is back. Since last year, historically unorganized workers at fast food and big-box retailers across the country have been demanding a higher minimum wage and better working conditions. They are gaining popular support as they become more visible, rallying in big cities and during attention-getting events such as Black Friday.

President Obama, liberals in Congress, and liberals seeking office are making the federal minimum wage a central plank in the effort to combat runaway inequality—now at levels unseen since the 1920s—and push back poverty. Obama has called for increasing the minimum wage from $7.25 per hour to $10.10, with a built-in cost-of-living adjustment tied to inflation. He later announced an executive order requiring federal contractors to observe the $10.10 minimum. And activists at the state and local levels have gone further. California may vote this year on raising its minimum wage to $12.

Increases enjoy wide public support. Recent polls find 76 percent of Americans support a $9 minimum wage. Republicans are split, with 50 percent backing an increase.

There are at least seven reasons voters, if not politicians, in both parties favor a higher minimum wage. They involve concerns about inequality and poverty, about responses to poor wage growth, and about the status of work as well as community. These reasons sometimes conflict, but overall they explain why the minimum wage will continue to play an important role in politics and policy.

• • •

Before looking at why people support a hike in the minimum wage, consider the current economic argument against it.

Many have claimed that raising the minimum wage will lead to significant job loss. The phrase “that’s Economics 101” is thrown around often in this argument, usually to shut down debate. It refers to the abstract, perfect, frictionless model of supply and demand. In this model, if the price of labor goes up—possibly because a floor has been set on the least amount a worker can be paid—the amount of employment goes down. Full stop.

But a wave of research since the 1990s finds little impact on employment due to a higher minimum wage, and some findings suggest that states with higher minimum wages see no negative employment effects at all.

In the world of economics beyond introductory supply and demand, you can find an explanation for why small changes in the minimum wage have little effect on employment. The economist John Schmitt notes three such explanations.

The first is consistent with the Economics 101 model but considers more factors. Here the higher price for labor is simply pushed onto customers. This is what people assume will happen when they say they are willing to pay a few extra cents for a hamburger if doing so will help millions of people escape poverty. In this story, a minimum wage increase would result in a one-time bump in the prices of goods produced by low-wage industries. And in these disinflationary times, a small boost to the price level might help with the greater problems in our stagnating economy.

The second explanation for the small impact of minimum wage increases is institutional. Here people look at mechanisms within firms that adjust to a higher minimum wage—for example, an increase in the productivity of workers that compensates for their extra pay. The minimum wage becomes an incentive for bosses to do a better job managing their employees. Higher earnings also encourage employees to work harder. Economists call this the “efficiency wage”: when workers have more to lose, they do their jobs better in an effort to keep their gains.

At the height of the postwar boom, the real value of the minimum wage was $9.25.

The third explanation adds two complications to the Economics 101 model. First, it is a pain to search for a new job. Second, employers pick the wages they offer their employees. This sounds obvious, but you won’t find it in Economics 101, according to which bosses pay a “market wage.” In such a scenario, if your boss paid a dollar less than the market wage, he wouldn’t be able to hire anyone at all, and if he tried to pay you a dollar less than the going wage for your labor, you would effortlessly get a new job at that old rate. Yet this is not how things work. People celebrate when they find a job because that search took real effort. It is not like buying a bag of apples or gas to fill your tank, tasks so simple that one can speak realistically of a market price.

This helps to explain why there are so many vacancies in the low-wage job market—vacancies that would be filled if the minimum wage were raised, thereby combating the fear of unemployment that accompanies any discussion of minimum wage hikes. A more generous minimum wage is not essential to hiring for these open jobs; employers could fill vacancies by offering higher wages, but they would in turn have to pay other workers this higher wage as well, meaning that filling vacancies would produce a higher overall wage either way. And since workers have to search for jobs, a higher minimum wage will increase the rate at which employees search for, take, and keep jobs. Empirical work by Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, and Michael Reich has found that a higher minimum wage leads to less turnover in low-wage jobs. This effect is visible in the international data as well.

A conservative estimate, such as the one recently offered by the Congressional Budget Office, holds that a $10.10 minimum wage would eliminate half a million jobs. Yet, even then, 900,000 people would be raised out of poverty, with more than twenty million people receiving pay increases. The CBO’s estimate overestimates losses while downplaying gains. But in spite of these numbers, there remains a strong case that the benefits outweigh the costs.

But why is this the case? What are the compelling reasons for a minimum wage hike?

1. Reducing Inequality

There are a variety of objections to high income inequality, even if equality is not the end goal: politicians become responsive only to the needs and demands of the wealthy; it may reduce opportunities for everyone, undermining social and economic mobility; it may lead to less innovation in all industries and contribute to deeper recessions and asset bubbles.

The effects of inequality are heavily researched and hotly contested. But one thing is clear: the falling value of the minimum wage is among the factors that have driven income inequality up over the past thirty years. According to the Economic Policy Institute, between 1979 and 2011 the real value of the minimum wage fell from $8.38 to $7.25 in current dollars. In 1968, at the height of the postwar boom, it stood at $9.25. There is debate about how to measure those dollar values across time, but there is no question that the minimum wage has also fallen relative to the average wage—from roughly 50 percent of the average hourly wage in the 1960s to 37 percent today.

Economists David Autor, Alan Manning, and Christopher Smith have shown that the minimum wage “held up” the bottom end of the wage distribution throughout the 1970s. The decline of its real value since then has gone hand-in-hand with increased inequality. This is particularly important in the bottom half of the income distribution, or between poorer workers and average workers. Economists refer to this as the 50/10 wage gap, a useful tool for measuring inequality between the middle class and the poor.

In addition to boosting the earnings of minimum wage earners, a minimum wage increase produces a well-documented “lighthouse effect,” where those workers who earn just above the minimum wage also see pay increases. The effects of a higher minimum wage propagate slightly up the income distribution, collapsing even more of the inequality in the bottom half of the income distribution.

2. Poverty Alleviation

Some minimum wage advocates don’t care much about income inequality per se. Instead, they are focused on alleviating poverty. Poverty has significant consequences for human flourishing, with especially pronounced effects on children.

A major mistake of the War on Poverty was its assumption that the economy would be capable of employing all people at generous wages as long as they had the right skills and as long as discriminatory obstacles were surmounted. Thus job training was a priority. However, during the ’70s, ’80s, and 2000s, wages at the bottom part of the income distribution fell, especially for men, even as the low-wage workforce became more educated. Education and technological advances alone could not solve poverty.

Recent research strongly indicates that raising the minimum wage reduces poverty. Dube finds that a 10 percent hike in the minimum wage would reduce the number of people living in poverty by a modest but significant 2.4 percent. It also shrinks the poverty gap—how far people are below the poverty line—by 3.2 percent. And it reduces the poverty-squared gap, a measure of extreme poverty, by 9.6 percent. So it provides meaningful benefits for the poorest individuals.

Larger increases would offer even more impressive gains. Raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would lift 4.6 million people out of poverty. It would also boost the incomes of those at the 10th percentile of the income distribution by $1,700 annually. That is a significant benefit for workers who have seen declining wages during the past forty years.

In a review of the literature since the 1990s, Dube finds fifty-four estimates of the relationship between poverty and the minimum wage. Forty-eight of them show that a minimum wage reduces poverty. This reflects a remarkable consensus among economists. The effect of an increased minimum wage on poverty is real, and it would be positive.

3. Poverty Alleviation, Again

Many policy analysts point out that if our sole concern is to reduce poverty, we can just give poor people money. Economists consider the minimum wage a blunt tool for fighting poverty, as its effects spread over broad populations, failing to isolate the poorest. And the government has other successful tools to narrowly target poverty, most notably the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

These are fair points. But the minimum wage is still an excellent and necessary weapon against poverty. Where other policy tools can’t reach, the minimum wage can.

As it is currently structured, the EITC does little to boost the income of those without children. Also, since one must be working in order to qualify for the EITC, the credit encourages growth of the labor supply and thus is likely to drag wages down for those who don’t qualify, allowing employers to capture part of the EITC’s benefits. According to government estimates, at least 20 percent of EITC payments are improperly paid. Some recipients claim too much by accident or by fraud; others don’t get the full value they were entitled to because the claims process can be confusing. And yearly payments are not that effective for poor people barely making it month to month.

A higher minimum wage doesn’t have any of these problems. It is practically self-enforcing. People who need it will get it, and it won’t require a massive tax-code bureaucracy to enforce. The income is given to people throughout the year, in each paycheck, rather than in a lump sum. One needn’t have children in order to benefit fully. To the extent that the EITC is captured by employers, a higher minimum wage will balance that out. There is no potential for fraud. And while the EITC costs the government money, which must come from other programs or new taxes, the minimum wage comes at no additional cost to taxpayers, except when it is applied to government employees (which is rare, since government jobs usually pay more than the minimum wage).

Once you consider how the EITC is implemented, the minimum wage makes perfect sense as a complement.

4. Gender Equality

The minimum wage affects women disproportionally, especially women of color. According to the Center for American Progress, more than 64 percent of those earning the minimum wage or less are women. African American and Latina women are 15.8 and 16.5 percent of female minimum wage earners, respectively, though only about 12.5 percent of employed workers.

Women are increasingly breadwinners or co-breadwinners in many households, and a higher minimum wage will allow for a family of three to be raised out of poverty on one full-time salary. Almost 80 percent of minimum wage earners are more than twenty years old. According to researchers at the Economic Policy Institute, the average worker affected by a $10.10 minimum wage hike would be thirty-five years old, with more than half working full-time. Twenty-eight percent of these workers have children. So this is not just a matter for teenagers without dependents.

It is important to understand how the service industry evolved from of a traditional vision of women’s role in the economy. The historian Bethany Moreton has argued that the emergence of Wal-Mart’s low-wage workforce can be seen as an extension of women’s perceived duty to care and serve. Without institutional mechanisms to ensure that service jobs and care work are compensated at breadwinner salaries, women’s wages will remain low.

This obstacle to gender equality will certainly worsen given that these same sectors are projected to generate the most jobs in the future, which will drive down wages for those employed in them. An increase in the minimum wage would buttress pay in these sectors enough to provide for single people and for families.

5. Good Conservative Policy

Conservatives have traditionally opposed the minimum wage, if only because they profess to dislike regulation of business. However, some conservatives are now offering strong support. Ron Unz, formerly of The American Conservative, has argued for increasing compensation for low earners and writes, “The most effective means of raising their wages is simply to raise their wages.”

Beyond the efficiency of the minimum wage as an intervention, conservatives who support it tend to do so for three reasons. All three derive from the idea that a higher minimum wage would make jobs more desirable.

First, it would help balance the huge uptick in the cost of higher education. Members of both parties worry that the government’s role in trying to increase college attainment has led to dramatic increases in college costs, as well as a predatory for-profit sector that lives off government funds in the form of student loans. Many marginal students are dropping out of higher education, leaving them with student loan debts and no degree. Meanwhile the job market continues to produce jobs that do not need to be filled by highly educated workers. Raising the minimum wage would make these jobs more desirable and give young people uninterested in higher education an alternate path to a decent living.

The average worker affected by a $10.10 minimum wage would be thirty-five years old.

Second, it decreases the cost of welfare. One of the central goals of conservative policy in the past thirty years has been to reduce government spending on welfare by getting people into jobs. However, if wages are too low, workers still need government income support such as food stamps or tax credits. Because these income supports are phased out as people earn more, the programs function like a tax, discouraging lower-wage workers from taking jobs or from working as many hours as they otherwise might. The minimum wage, by contrast, provides income support but without the discouraging effects of welfare.

Conservatives’ third reason to support a minimum wage increase has to do with undocumented workers and immigration. A higher minimum would make low-wage jobs more desirable to Americans, and in turn employers would rely less on undocumented workers. The current bipartisan consensus involves a massive policing, detention, and deportation apparatus designed to deal with undocumented workers, with President Obama presiding over the greatest number of deportations in any two-year period in U.S. history. Under President Bush, local police were tasked with enforcing federal immigration laws, blurring the distinction between criminal and civil enforcement of immigration law. This has produced a human rights disaster that could be mitigated by a higher minimum wage, which would help Americans get back into the vacancy pool currently being filled by undocumented workers. We would have less contention over immigration if Americans felt that the jobs undocumented workers take were jobs worth filling themselves.

6. Civic Republicanism

When low-wage workers protest at fast food restaurants, low wages are not necessarily their sole concern. The working conditions may be equally important. Between a lack of sick days, random shift scheduling, and working without pay, there is a host of problems and humiliations from which workers seek redress.

Civic republicanism presses against these practices. Philip Pettit,

the philosopher most associated with this strain of thinking, defines its goal in terms of “freedom as non-domination,” freedom “as a condition under which a person is more or less immune to interference on an arbitrary basis.” In what sense can people be considered free if their means of survival places them at the mercy of an erratic schedule, thereby preventing the formation of civic and communal ties? Surveys of New York City’s low-wage workers find that 84 percent of them are not paid for their entire workday. When bosses can flout labor contracts and arbitrarily impose working conditions in this way, workers lack the kind of freedom that civic republicans celebrate.

By making the labor market tighter through lower turnover and vacancies, a higher minimum wage creates bargaining power for workers and will help to eliminate these kinds of domination.

7. A Just Wage

Catholic doctrine provides a religious case for a minimum wage, which is all about balancing the needs of the family with those of the marketplace. As Pope John XXIII argued in a 1961 encyclical, the wage of the poor “is not something that can be left to the laws of the marketplace,” as “workers must be paid a wage which allows them to live a truly human life and to fulfill their family obligations in a worthy manner.” In the words of Pope John Paul II, “A just wage is the concrete means of verifying the whole socioeconomic system.”

The Catholic argument for a higher, or “just,” minimum wage has a long history. In 1891 Pope Leo wrote that there must be “proper concern for the worker so that from what he contributes to the common good he may receive what will enable him, housed, clothed, and secure, to live his life without hardship.”

As the writer Elizabeth Stoker explains, the Catholic Church particularly fights against the idea that

someone should do honest, hard work but still not have enough money to support their family. Work should be done in the service of supporting a family, so therefore when work is done and yet still families are unsupported, the whole ordering of human priorities is thrown awry, and the intrinsic good of the family is threatened.

• • •

Politically, the minimum wage is attractive because it can be tackled at different levels. Where Congress might remain bitterly divided, states can take the lead in pushing for change. And where states fail, cities and communities can step in. Opponents of minimum wage laws are aware of this. If you look at the corporate conservative lobbying agenda as presented by groups such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), you see efforts to pass state laws that overrule local minimum wage hikes. It is an ironic position for an intellectual movement that prefers local control.

It will be interesting to see how these arguments are deployed as the 2014 elections approach. Democrats seeking office will likely continue to frame Republican efforts to fight equal pay and reproductive choice as a “war on women,” and linking the minimum wage to such an argument would be powerful. Republicans, such as Marco Rubio, who want to reinvent the policy framework by relying on tax credits rather than guaranteed wages, are not prepared to allocate money to the effort, which will limit the appeal of their ideas.

Ultimately, claims about fairness and the proper functioning of the market will carry the day. President Obama and other supporters of a minimum wage increase will keep pointing out that it is wrong for a full-time worker with a family to live in poverty. It is on this argument, and on the bargaining power of low-wage workers, that the minimum wage campaign will be built.

Photograph: Stephanie Keith