New Lefts: The Making of a Radical Tradition

Terence Renaud

Princeton University Press, $29.95 (paper)

In a late 1968 essay on the general strike in Paris that spring, the editors of the New Left Review declared a revolution. “How do we explain this sudden switch of consciousness,” they asked, “this abrupt reversal from acceptance to rebellion, from obedience to mutiny?” May 1968, as has been commemorated many times over, was both a culmination and a rupture extending far beyond Paris. It crystallized a global New Left comprised of various, radical youth-led organizations while marking a generational break from an “old left” sullied, as its critics saw it, by accommodation to welfare capitalism, cultural conformity, law and order politics, and imperialism.

Yet exactly what May 1968 amounted to—and the legacy of the sixties New Left more broadly—is a source of continuous debate. In an exchange of letters published in the New York Review of Books in 2010, during the depths of the Great Recession and with Occupy Wall Street yet to come, historian Tony Judt insisted, “a general strike is not axiomatically ‘revolutionary’ . . . it needs leadership.” He emphasized further that the “strikes and sit-ins of 1968 were remarkable for their spontaneity—but for just this reason they lacked any coherent strategy or goals.” In important respects, Judt’s assessment was rooted in a sober understanding of the major political developments and backlashes that followed the social movements and rebellions of the 1960s. During the 1970s and 1980s, Europe and the United States had witnessed the breakdown of a largely social democratic order. Increasing fractiousness on the left and the steady dealignment of workers from center-left and leftwing parties only underscored that neoliberal policies had dramatically altered political discourse and made yet more remote the horizon of radical possibilities. Concrete policy agendas may be prosaic, Judt seemed to imply, but they articulate a path that society can take.

At the same time, Judt’s more caustic reflections on “68ers” marginalized their connection to a pattern of periodic leftwing revitalization, one that has waxed again in recent years. Over the last decade there has been an explosion of mostly nonhierarchical social movements rivaling the energy of 1960s radicals and protesters. Their targets are formidable and interconnected: unprecedented economic inequality and politically shielded concentrations of wealth, fascistic militarized policing, persistent forms of racial injustice, and the ever more urgent climate crisis. Though these movements have so far proved fragmentary and may lack the kind of euphoric optimism that helped galvanize their antecedents, neither are they afflicted by the fatalism that came to mark Western lefts at the height of globalization, when internationalist class politics had largely faded from view, center-left parties embraced markets, and debates about the “end of history” abounded in intellectual circles. Wary as these new movements are of formal political power, they are nonetheless determined to influence it and change the way society perceives injustice.

Today’s movements are therefore consistent, in historian Terence Renaud’s estimation, with a long leftwing tradition of interrogating the methods and forms that can ultimately build a post-capitalist world. In his compelling new book New Lefts: The Making of a Radical Tradition, Renaud illuminates the origins of a distinctive sociopolitical formation he calls “neoleftism,” defining it as an attempt within leftwing groups to “prefigure . . . the kind of participatory democracy and popular control that they expected from a future, postcapitalist society” in order to preempt a turn toward oligarchy within their own movements. Renaud’s unique framework provides an extended chronology and account of the transnational dialectic between different leftwing groups that will be especially elucidating for readers in the United States. Familiar American New Left references—such as sociologist C. Wright Mills, the anti-war and civil rights activism of Students for a Democratic Society, and the emergence of “new social movements” that eventually eclipsed older modes of class politics and radicalism—are placed, alongside their more militant European contemporaries, in a much larger context. This innovative history reveals the broader geographic and temporal contours of neoleftism, tracing its origins back to the small intellectual circles and clandestine political groups of late Weimar and early Nazi Germany, exploring their links to the Spanish Civil War, Germany after the Nazis’ defeat, and finally France during the general strike of May 1968.

The key dilemma for each successive wave of neoleftism, Renaud argues, was how to “sustain the dynamism of a grassroots social movement without succumbing to hierarchy, centralized leadership, and banal political routine.” Today, Black Lives Matter, climate activists, and other progressive groups have similarly grappled with how to successfully challenge injustice while maintaining vitality and independence from the existing political system.

New Lefts begins by showing how an antifascism rooted in heterodox Marxism was critical to the identity of the first new left that emerged during interwar Germany. The secretive cohort known first as “the Org” and then “New Beginning” was influenced by theorists such as the young Hungarian György Lukács, whose critique of modern industrial society extended beyond the orthodox Marxist analysis of the structure of the class system, working-class party organization, and the “scientific” belief that capitalism would precipitate its own downfall—a juncture at which a revolutionary proletariat would permanently seize the means of production. “Reification,” Lukács argued—the process by which capitalist commodity exchange objectifies the whole gamut of human social relations—explained why industrial society produced atomized workers estranged from both a sense of personal agency and collective identity. Such alienation conditioned workers to accept the governing mechanisms of capitalist society—its laws, institutions, and intrinsic exploitation. As advanced capitalism permeated and thus commodified every aspect of existence, workers would more readily reproduce this false consciousness, even if at times they registered the cruelties and indignities of harsh working and living conditions.

In Renaud’s telling, Lukács’s major insight from his 1918–1919 period lay in showing how workers’ parties that operated within the parameters of bourgeois democracy were prone to emulate the institutions that upheld capitalist society. Not only did party politics fail to substantially ameliorate repression and alienation, it stultified and corrupted workers’ movements to precisely the extent that workers’ parties and trade unions formalized internal hierarchies and participation in capitalist institutions. On this view, Renaud explains, even when the parties that subsumed the proletariat sought progressive ends, they ultimately led to “bureaucracy, institutionalization, and cultural stagnation,” threatening to extinguish radical consciousness and revolutionary action.

Renaud notes that while this critique was aimed foremost at the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) and its increasingly reformist orientation, Lukács also warned—in his 1923 collection History and Class Consciousness—that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was likewise susceptible to this kind of ossification. Though he was moving toward a disciplined embrace of the Soviet Union, Lukács’s critique positioned him, somewhat vulnerably, between Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg. According to Renaud, he was alert to the problem that a Leninist vanguard party could become insular, yet he also viewed Luxemburg’s faith in the revolutionary capacities of spontaneous mass proletarian action as insufficient and naïve. Identifying the revolutionary councils of the early Soviet period as the ideal expression of worker organization, Lukács saw leftwing intellectuals as essential to disseminating the ideas that could transform proletarian consciousness, culture, and agency, and thus preempt or overcome the social constraints and corruption posed by bureaucratization.

Complementing Lukács’s influence were the ideas of another Hungarian, sociologist Karl Mannheim, who argued in 1928 that generational consciousness was formed through a common social experience of the profound events that transform society at large. As a “social construction,” Renaud summarizes, a generation could form an identity across various class and cultural distinctions through participation in organizations that forge a shared sense of position within history. Importantly, generational consciousness did not have to conform to strict age boundaries in Mannheim’s theory. World War I, the failure of postwar revolutionary movements to gather force in Western Europe, and the spread of rightwing and fascist groups throughout the 1920s would link older and younger leftwing cadres who disputed the efficacy of reformism and working-class political institutions.

Germany’s incipient neoleftists further expanded Lukács’s and Mannheim’s critiques in the early to mid-1930s to account for National Socialism’s terrifying ascent, arguing that it was a genuine mass phenomenon that the established socialist and communist parties had failed to stop. “Convinced that beating fascism required a total revolution of all spheres of life,” Renaud writes, the cadres of New Beginning and related groups “created a subculture of defiance that would persist even after World War II.” But unlike Lukács and other Western Marxists who would shore up their standing with the Soviet Union, interwar Germany’s neoleftists maintained a heterodox approach, given that many were expelled from or had left the Communist Party. New Beginning thus pulsed with ideological and strategic positions at odds with both the SPD and the Comintern. Social Democracy, in the view of the Org/New Beginning’s founder Walter Loewenheim and other neoleftists, had led to entropy and division on the left, its compromises with the capitalist state and conservative interests assuring timidity toward the fascist threat. And though Loewenheim and his cohort were animated by ideals of revolutionary praxis inspired by the Russian Revolution, the group gradually recognized that doctrinaire vanguardism could easily and quite brutally betray socialism’s emancipatory promise by entrenching new elites. The Stalinist turn in the Soviet Union only heightened their suspicion that the communist state was ossifying into an ever more coercive bureaucracy.

As much as these cadres envisioned a new foundation for left unity, they were fixated on perpetuating ideological renewal above all else—an arguably elitist obsession that would inhere in, and frequently hinder, subsequent new lefts. Nevertheless, their antifascism reverberated, both spatially and temporally, beyond their modest memberships. Through carefully disseminated “modules” and pamphlets, including a widely read 1933 manifesto, Neu beginnen!, they transmitted throughout Western Europe a heterodox Marxism that sought to inculcate a revolutionary culture that embraced experimentation with new organizational methods. Following Lukács’s earlier path, this effort expanded the realm of socialism’s emancipatory language even as Loewenheim demanded discipline from his recruits. Other leading members would challenge Loewenheim’s control over the group not long after its inception, connecting its vision of Marxism to other emerging theories of society, psychology, and sexuality. As neoleftism became inflected with Wilhelm Reich’s theories of patriarchy and sexual liberation, for example, the goal of inciting radical democratic self-organization through pedagogy expanded to include not just traditional industrial workers but all humans under the yoke of conservative institutions and social domination. Alternative, non-hierarchical modes of decision-making and social reproduction would demonstrate that substantive political acts could, in fact, be unmediated by formal party structures or “bourgeois” parliamentary systems.

Following the decisive events that consolidated the rise of the Nazi state and Hitler’s dominance within his party—the Enabling Act of March 1933 and then the Night of the Long Knives in 1934—many German neoleftists went into hiding or exile, although some endured sentences in concentration camps. Developments in Spain, meanwhile, drew the attention of émigrés in search of a new epicenter for revolutionary action. Like their counterparts from the Weimar era, Spanish leftists were divided over the opportunities presented by the Second Spanish Republic that was proclaimed in 1931, which had given the Spanish Socialist Party its first taste of power in a coalition government. A coal miners’ strike in October 1934 precipitated a general strike that the government crushed through extraordinary violence, fracturing the Socialist Party. Some leftwing militants seized local and regional administrations, as the miners had attempted, while a growing number of small group experiments embraced feminism, anarchism, and related forms of radical communitarian autonomy from the state.

By the time civil war broke out in 1936, the more conservative wings of the Spanish Socialist and Communist parties had eventually coalesced to defend the Popular Front government, yet an alternative coalition of more revolutionary groups had already formed in 1935. Renaud explains that the Poumistas, as they came to be known, demonstrated the kind of praxis that New Beginning had sought to model for the German left. The Poumistas’ approach to recruitment and organization grew out of their antifascist, anti-authoritarian thinking: workers, peasants, teachers, intellectuals, and other committed leftists banded together to form egalitarian committees and militias—including all-female battalions—in the service of revolutionary self-government and resistance to rightwing forces. While the exigencies of war would require the Poumistas to establish more formal structures for their militias, they would still attract hundreds of émigrés from Germany and Italy specifically inspired by the Poumista model. Ultimately, serious fratricidal violence between antifascists in 1937 would diminish the Poumistas and the viability of the revolutionary practices they pioneered.

Renaud’s discussion of the Poumistas underscores the fact that there were multiple vectors of a transnational left participating the Spanish Civil War, several of which were not aligned with or were openly critical of the Soviet Union and Soviet-backed forces. The Poumistas, writes Renaud, had argued that the “control” of Stalinist bureaucracy “over the Comintern posed a real danger to the international working class.” This opposition initially went further than the critique leveled by New Beginning, whose members generally still hoped that the Soviet Union would be an agent of revolutionary progress and who believed a united front between Communists and other leftists remained desirable and attainable. But New Beginning’s early wariness of Stalinism morphed into full-blown disillusionment as the 1930s wore on.

Richard Lowenthal, one of the group’s key theorists, came to view the Communists’ strategy behind the Popular Fronts of Spain and France as insufficiently revolutionary. As Renaud summarizes it, Lowenthal believed they “had reduced antifascism to an ideological minimum. . . . antifascists needed a robust socialist program that went beyond a rearguard defense of electoral democracy.” This perspective may seem ironic given neoleftists’ own pragmatic emphasis on cooperation across leftwing groups. But as Renaud reiterates throughout New Lefts, neoleftism always contained an unstable dual purpose—to constantly revitalize its grassroots basis, yet at the same time establish durable alliances that could transcend internecine conflict. For neoleftists like Lowenthal, evidence was mounting during the Popular Front era of the mid-late 1930s that the Soviet Union’s engagement in antifascist struggle was increasingly hollow and cynical.

The greatest source of alarm would far exceed the bleak degeneration neoleftists had feared in their early critiques of Stalinist bureaucracy. The abduction and murder of an associate in Spain by Soviet agents, followed by news of the Moscow show trials, had fueled New Beginning’s despondent outlook. The breaking point came with the August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop pact that sealed nonaggression between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (until Hitler breached it in the summer of 1941). In response, Renaud notes, “Lowenthal claimed that Soviet motives made sense only when judged from the standpoint of raw geopolitics.” He would go on to develop a critique of “Russian-German Bonapartism,” which, while not equating the two ideological-political systems, concluded that both now threatened a permanent counterrevolution to the goals of emancipatory socialism.

Alongside other developments—New Beginning’s relocation of its foreign bureau from Paris to London, the growing concentration of émigré networks in the United Kingdom and New York City, and even the appointment of neoleftist émigré scholars to colleges in the northeastern United States—these judgments marked the start of a broader transformation for the non-Communist, nonparliamentary left. “Despite their opposition to capitalism, bourgeois democracy, and militarism,” Renaud writes, “many antifascist new lefts would transform into cooperative partners in the Allied war effort”—participating in propaganda efforts, intelligence gathering and analysis, and related activities. Significantly, the Soviet Union joining the Allies after its invasion by the Nazis would not alter this trajectory. Reconciliation among segments of the non-Communist German left through the Union of German Socialist Organizations in Great Britain would in turn lead to a “process of ideological moderation” that “foreshadowed the postwar modernization of Social Democracy.”

The war effort and ensuing practical dilemmas over how to reconstruct and democratize occupied Germany brought key neoleftists who once proudly operated along the margins of traditional politics into the formal processes of party-building and policy-making. Renaud explains that, in addition to the experiments witnessed in Spain, the extended experience of being refugees further broadened neoleftists’ understanding of what social strata could be part of a mass base of workers. “This new concept provided a template for the postwar transformation” of the SPD “from a class party into a popular party,” Renaud writes, but, importantly, it also reflected a gradual “assimilation of liberal democratic norms.” To sustain antifascism under conditions of war had required hope, and thus pragmatic decisions and compromise.

The revival of communist circles in the Soviet zone of occupied Germany along with the U.S. military’s restrictions on political activity elsewhere reinforced the need for a new strategy. Regrouped neoleftists—most of whom survived the war—could either commit themselves to party politics and shape political and economic outcomes or yield to a binary between conservative administration in the West and Soviet dominance in the East. While once again some entertained bridging divides with the Communists, “antifusionists” such as Kurt Schmidt believed, in Renaud’s words, that the SPD’s internal democracy made it the best vehicle to structure “German political life independently from the great powers.” This required neoleftists joining forces with old guard Social Democrat leaders such as Kurt Schumacher, on the one hand, while reinvigorating party membership with a new generation, on the other. Notwithstanding neoleftists’ prior radical convictions—which did not completely dissolve in the immediate aftermath of the war—the turn toward building a popular party ultimately meant a strategic appeal to middle-class professionals and those aspiring to class mobility, not the recreation of a “Popular Front” or similar expressions of romantic left populism.

The leveling effects of total war, the imperatives of denazification, and opposition to the Soviet Union, Renaud concludes, forced neoleftists who wanted to be a part of a new, democratic future for Germany to more fully engage in the nuts and bolts of political economy. What programs would they advocate, and what were the best ways to build popular support for them? These conditions entailed a different approach to renewal, one that was considerably less ideological and theoretical in emphasis than what New Beginning had enunciated in the 1930s. Renaud chronicles the groundwork former neoleftists embarked on against the backdrop of the Cold War, showing how they became Social Democrats while navigating the conservative atmosphere of West Germany under Konrad Adenauer’s governing Christian Democrats.

By the end of the 1950s, renewal meant excising Social Democracy’s most overt ties to Marxism. In Renaud’s view, the SPD’s watershed 1959 Bad Godesberg conference represents its “final peace with the institutionalized party form, the geopolitical status quo, and democratic capitalism. . . . Under the banner of renewal and modernization, the SPD ironically cemented its place in the old left.” Lowenthal, who by then was an established journalist and public intellectual, believed that the crises of the 1930s and the changes induced through war mobilization and economic recovery meant that aspects of socialism now characterized all Western democracies, even those with conservative governments. The task of Social Democrats, then, was to formulate a way of regulating the economy that embraced the principle of democratic control through technocratic intervention.

The SPD would effectively follow this prescription to reform the state via its commitment to a Sozialstaat, that is, a broadly redistributive welfare state. Yet its program, Renaud emphasizes, also assured the party would protect private property and advance the interests of small and medium-sized businesses. Pro-market assurances arguably foreclosed a transition to democratic socialism; in retrospect, the SPD’s positions and attendant electoral strategy were analogous to the post–New Deal Democratic Party, whose growing middle-class base of salaried professionals and increasingly poll-tested management of interest group politics represented the future contours of Western Europe’s center-left. What is more, the SPD’s program foreshadowed the axioms of Third Way neoliberalism. “Free consumer choice, free choice of employment, free competition, and free enterprise” were clearly stated principles, Renaud notes. Instead of instrumentalizing the state to achieve the highest possible wage compression and the maximum transformation of ownership in the economy while still upholding the rights of democratic citizenship—an approach to political economy that Scandinavia’s social democratic parties were undertaking—the SPD limited its vision to humanizing and making more generous the social market economy that had been largely constructed by Christian Democrats and ordoliberal economists.

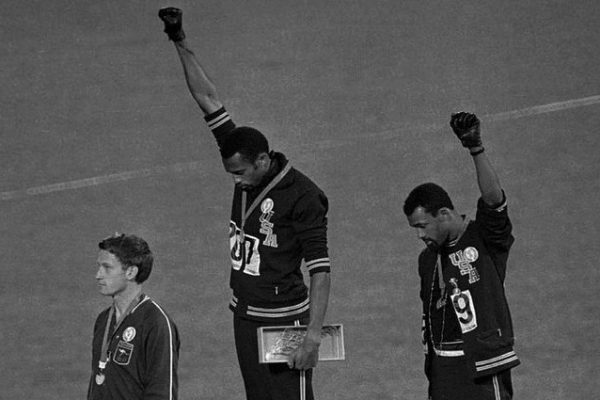

This caution displayed by center-left politics in West Germany deepened a growing frustration among young German leftists that was mirrored by their counterparts throughout Western Europe and North America. For leftists coming of age during the height of the Cold War, generational consciousness was informed perhaps as never before by the global structure of the capitalist system and knowledge of the injustices and exploitation contained therein. In the final part of the book, which turns to the intellectual and activist currents that would constitute the global sixties New Left, Renaud writes that the interwar new left was at once “a specter of attraction and aversion” due to its own postwar peace with reformism. While different examples of violence and oppression sparked grassroots mobilization across Western Europe and North America—the wars in Vietnam and Algeria and systemic racism against Black Americans in the United States among the most salient—these currents converged in their critique of capitalism and the inequities that existing welfare states and center-left parties could not paper over.

The transnational dimension was further heightened by student movements whose critiques were informed in part through the ascent of influential leftwing philosophers and social scientists in colleges and universities. Like the student movements, these professors had to contend with a deeply conservative milieu—and in cases like socialist political scientist Wolfgang Abendroth’s, the presence of former Nazis among faculty. Although they similarly occupied the node in leftwing politics that New Beginning had fashioned for itself, their critique of liberal democracy was updated to reflect the tenuous social peace secured by the postwar order. Abendroth, in particular, articulated the idea of an antagonistic society percolating under the ambiguities of West Germany’s constitution, whose Article 15 conceivably allowed for a progressively socialized economy. The great obstacle to a more egalitarian use of the state was, in Renaud’s summary, the fact that “in an antagonistic society, one could never trust the ruling class to respect the law and not rely on violence in an emergency.” Insofar as the rule of law could be subverted by economic elites, fascism remained a latent threat even in democracies that had codified a degree of social and political rights that, for millions of people, did not exist prior to 1945.

It was in this climate of intellectual awakening, where the façade of liberal democratic norms was interrogated, that Marxism and nonparliamentary leftism was reclaimed by a new generation. Echoing their interwar predecessors’ critique of bourgeois democracy, the emergent New Left targeted mainstream center-left parties—the continent’s social democrats, Labour in the UK, and the liberal wing of the Democratic Party—for their complicity with a system rife with hypocrisy and injustice. Deepening knowledge of anticolonial struggles and socialist movements in developing countries further amplified how the New Left comprehended the coercion that built democratic capitalism in the industrialized world. Though both European and American leftists shared the principle of advancing participatory democracy, domestic political contexts would shape the demands and goals of respective groups. In the United States, the 1962 Port Huron Statement by Students for a Democratic Society, for example, called for “a movement for political as well as economic realignments,” endorsing the formidable task of restructuring the Democratic Party to help achieve its ends. Such a proposed reconciliation of liberal and socialist currents—aiming at a purposeful polarization of the American two-party system—contrasted with European Marxists’ effort to form an alliance that transcended traditional party politics altogether. France’s May Movement in 1968 would mark the apotheosis of postwar leftists channeling the direct action and cross-sectoral (and transnational) alliances envisioned by their neoleftist predecessors. For a brief moment a kind of prototypical left populism mirrored the “popular,” catch-all strategy and identity of mainstream social democrats. “The greatest ambition of the sixties New Left,” Renaud writes, was to “imagine untried coalitions across university, factory, and colony.”

But in addition to all the external and nefarious factors that could undermine such coalitions, it is possible to discern at least two intrinsic problems in the developments Renaud relates. Despite pronouncements to the contrary, there was no real equality of position between university students, industrial workers, immigrant day laborers, and distant revolutionaries waging national liberation in the Global South. In other words, the “horizontalism” of a radically democratic general assembly that dissolves both bureaucratic political leadership and the stark social hierarchies of capitalism was lacking. Nor was there clarity and agreement over specific near-term ends between the most radical students and the workers that would inevitably have to return to the regimentation of factory life. The students were in the foreground and the most itinerant, by status and inclination. Summarizing the interpretation offered by the French sociologist Alain Touraine in the early 1970s, Renaud writes that the “leaderless” New Left led by charismatic students “marked the ascent of a new working class” outside traditional modes of production, one oriented to battling technocracy and fostering a new intelligentsia. As Renaud emphasizes, the New Left mimicked capitalism’s creative destruction in calling for new forms and methods of action against the status quo. We might extend the analogy further. More than supplanting the old bureaucratic left, the New Left helped catalyze the obsolescence of mid-twentieth century working-class culture, dependent as it was on place-bound solidarity and long-cultivated relationships between unions and their traditional political allies.

For these reasons and others, a certain ambivalence toward aspects of the sixties New Left is understandable today. Its contradictions loom for people who see in themselves the same kind of yearning for a new world but also a thread between that era’s counterculture and the ease with which educated society elevates an aestheticized intellectual life and political “values” over the drudgery and infrequent victories of sustained activism. The May Movement’s legacy depends in part on a quasi-hagiographic mystique cultivated over time, as its example became a touchstone of radical imagination. But it was precisely while this scene of revolutionary action came to be more and more celebrated that actual possibilities for radical change—or even for more prosaic visions of postwar progress—began rapidly to unravel. Several decades of neoliberal governance later, a certain disillusionment seems inevitable among those who see the sixties New Left as failing to anticipate how “liberation” would blend seamlessly with market expansion on the one hand, yet also give way to reactionary cultural conservatism, on the other.

Of course, critical hindsight should not cloud the context in which the May Movement took place, nor should it diminish the authenticity and significant contributions of its confrontation with the state, capitalism, and cultural conformity. Still, as powerful and unprecedented as the May Movement was in the postwar era, its rash of action committees and other forms of revolutionary organizing were not destined to take root for the long haul. As Renaud makes clear, the French Communist Party and the unions aligned with it were begrudging participants, seeking instead to control events through the general strike. If the New Left can be faulted for overly romantic notions of revolutionary power, the old left was terminally marred by its paucity of imagination, as reflected in its meager goals of higher wages and incremental reform. For so much at stake, a better bargain under democratic capitalism was the preferred outcome—even as it would become increasingly elusive following the economic shocks and policy realignments of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Where does this history leave us? Renaud’s study provides a new way to examine the origins of the New Left and the underappreciated temporal links between European leftists who, at the peak of their radicalism, shunned party forms yet wielded outsized influence. The arc depicted is knowingly Eurocentric, though Renaud frequently gestures toward the implications of a grassroots transnational leftism spreading out from Europe’s industrialized core, leaving us to reflect on how it intersected with Marxist and left populist movements in Latin America and other developing or decolonizing countries, as well as its potential resonances with democracy movements and workers’ strikes in the communist states of central and eastern Europe. Among Renaud’s central contributions is the spotlight he casts on key leftist intellectuals less known to English-speaking audiences, purposefully rebalancing the attention typically devoted to the Frankfurt School.

The book is also a careful treatment of changing beliefs, rivalries and factions, and changing political circumstances—no small feat given the twists and turns involving multiple generations of cadres who were not vanguardists in the traditional sense, but still important nuclei of alternative leftwing thought. Renaud is plainly sympathetic to both the original neoleftists of the interwar period and their successors in the 1960s for their passion, courage, and intellectual restlessness. Critiques of bureaucracy were often well-founded. The “68ers” were especially prescient about the increasing conservatism of the French Communist Party, which, before its rapid decline after the end of the Cold War, adopted a pronouncedly restrictionist position on non-European immigration in the early 1980s, in contrast to the Socialist government of François Mitterrand.

At the same time, Renaud does not shy away from evaluating neoleftists’ shortcomings, including frustrating instances of myopia and, sometimes, the dissociation from concrete political goals and conditions, despite—or perhaps because of—their own experiences of state violence and exile. Perhaps ironically, both Leninists and moderate social democrats would criticize neoleftists for their “infantile” and romantic anti-capitalism. But as New Lefts amply documents, neoleftists, by virtue of the intermediate position they carved out between Social Democracy and Soviet Communism, generated powerful new insights about political institutions, culture, sex, gender, and imperialism that the usual party forms and traditional party insiders could not produce.

On the perennially thorny issue of pragmatism and reform, New Lefts mostly withholds final judgments about the lessons activists and policy oriented leftists today might draw from the legacy of mid-twentieth century new lefts. Renaud stresses that “political power was never the main goal. . . . Young militants . . . were not interested in building a new parliamentary coalition.” He adds, “Seizing the state was peripheral to the neoleftist project, despite what antileftists might have feared.”

For many, however, this neoleftist fixation on “renewal” will come across as excessively romantic and, perversely, borderline anti-political. In retrospect, at a moment when the right has only strengthened its grip across the United States and parts of Europe, this refusal to pursue specifically political—as opposed to social or cultural—power will look to some like a grave mistake. New Lefts imparts a feeling that neoleftists, at peak moments of direct action and grassroots democracy, were consumed by the rapture of anticipation—of a cataclysm, or even total social revolution. Yet their reflexive opposition to the party form impeded greater leverage, and thus the recognition that some concessions from capital and the state are worth getting, that better conditions need not come at the expense of still more radical goals. It is undeniable, furthermore, that the welfare state made it possible for the sixties New Left to emerge as it did and occupy the cultural and political space it chose. This does not mean its critiques were unfounded; on the contrary, they were absolutely essential. But one must be clear-eyed about the limits of rejecting the pursuit of political power.

Though it is not a conclusion New Lefts pursues explicitly, a lesson one might draw from Renaud’s book is that the central problem for a radicalism committed foremost to critique rather than to political power is that actually implementable welfare state programs for distributional change and decommodification begin to appear objectionably conciliatory or reformist. This orientation runs the risk of leaving the world as it is, perpetually deferring a better world to a time that never comes. In this sense, any leftism without a concrete policy agenda—and the tactical focus needed to win the formal power to implement it—is ultimately a betrayal of its overriding aim: to create a more just world. An ideology of strict opposition, legible only to fervent insiders, ultimately abandons the practice of world-building to others, from those who circumscribe and redefine human rights to suit maximal market freedom to those who recreate a fortress nation-state along chauvinist ethnocultural lines.

In his epilogue, Renaud suggests that contemporary social movements, particularly the wave of Black Lives Matter protests over the summer of 2020, are channeling the most vibrant aspects of previous new lefts. The boundaries between radicals and institutions, civic or political, do appear more porous than they have been in a long time. In the United States, there are once again elected progressives in the mold of social democrats—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib, Ilhan Omar, Pramila Jayapal, and Cori Bush, among others—and they have been empowered through diverse constituencies and a multitude of strategies, in turn amplifying ideas that were once only aired in a university, small radical book club, marginal nonprofit, or underground magazine or blog.

Some observers, of course, will conclude that the modern course of electoral and legislative politics in the United States confirms that a neoliberal logic of social and fiscal discipline will prevail over even highly pragmatic reforms. The steady erosion, thus far, of Biden’s economic agenda by intransigent centrist Democrats is only the latest reflection of the Democratic Party’s decades-long capacity for self-inflicted damage, Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema only the most visible of the stubborn obstacles preventing the party “realignment” once envisioned by the authors of the Port Huron Statement. At all levels of government there are Democratic defenders of the status quo that the left must contend with, and still other institutional obstacles—from the Supreme Court to gerrymandering—besides. Nor are the obstacles unique to the United States. In Germany’s recent parliamentary elections, Die Linke’s disappointing results underscore that leftwing infighting and a lack of clearly defined political objectives continue to harm the broader public’s reception to progressive challenges to the status quo.

Still, there is some cause for optimism—and it will be needed, given the immense challenges before us. Through a still-evolving mix of grassroots mobilization and electoral politics, the U.S. left has accrued influence it simply did not have even ten years ago, raising the profile of social democracy in the process. Indeed, the idea of Bernie Sanders serving as chairman of the Senate Budget Committee would have been inconceivable before his 2016 campaign. Any young European leftist must welcome the possibility that a true break from neoliberalism in the United States might consequently alter perceptions in Europe. In that case, the U.S. left could justly be credited with helping to dismantle an international policy regime that has fueled inequality and maintained poverty across much of the globe for decades. And while it is necessary to closely scrutinize the tempo of change and the actual policy results, it is at the very least clear, through the rhetoric of American progressives, that crucial links between egalitarian economic goals and other forms of social justice have been reestablished.

The amalgamation of putatively non-party and coalition-building strategies further reflects the unprecedented transnational, multiracial character of modern lefts in the West. While many factors might lead one to conclude that they are incurably weak and incapable of transformative agency, the prominence of nonwhite leftists—who know the difficult legacies of racialized and stratified welfare states but nonetheless seek to retrieve and update their best mechanisms—signals that social democracy has the potential to be reborn, as it was in Europe’s apocalyptic landscape of 1945. In this context, New Lefts reminds us that world-building can take many forms. But at the same time, it also reminds us that neither a position defined through the negative—such as antifascism—nor a political-economic blueprint can suffice on its own. In the face of the climate crisis and rampant social and economic inequality, far-sighted activists will have to discern how to weave in and out of institutions, building power in one key while nurturing the fire of radicals in another.