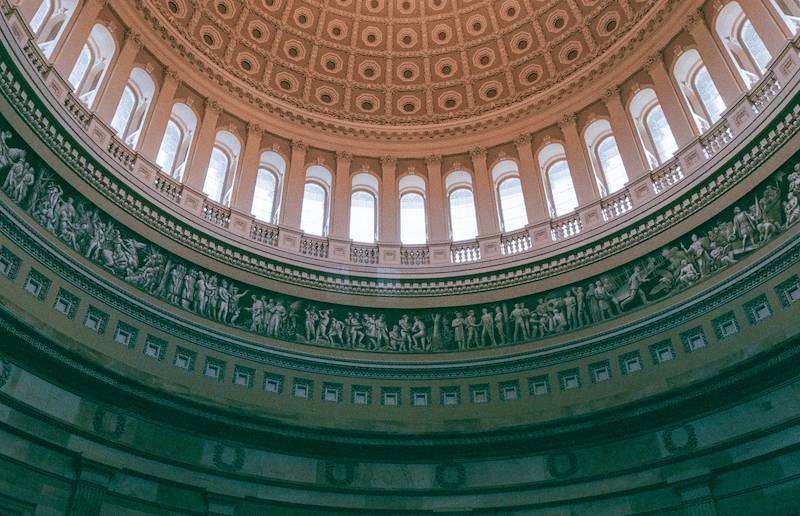

Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism in the American Revolution

Gordon S. Wood

Oxford University Press, $24.95 (cloth)

The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America

Carol Anderson

Bloomsbury, $28.00 (cloth)

“Our Constitution is so old,” says Heidi Schreck in her 2019 Pulitzer– and Tony–nominated play What the Constitution Means to Me. The line is a deliberate double-entendre, its meaning turning subtly on intonation. On the one hand, it captures the complaints of those who want to change the system—so old carrying the sense of obviously obsolete. On the other hand, it gestures at the reverence of those who think it’s our rock—so old, in this case, meant as a badge of honor. By binding these two visions together, the line also gives expression to the ambivalence of liberals like Heidi and me, who were taught to believe that the Constitution can and does change but have learned to wonder about who has benefitted from its protections, much less its ambiguities.

Lately, the debate about whether the Constitution is the problem or the solution has reached a new level of intensity. An older standoff between originalist jurisprudence and living constitutionalism has come to seem quaint, especially in the face of design flaws, from the Electoral College to the Senate, that critics allege have never been addressed, much less fixed. The controversy is as weighted and as polemical as the famous debates between the Ancients and the Moderns over the value of Greek and Roman classics, a debate that in many ways set the stage for the Enlightenment, the Age of Revolutions, and the Constitution itself. Historians find themselves working overtime, called in as consultants, their work on the distant past suddenly rendered relevant. Two new books reveal the widening gulf between those who see the Constitution’s age as a sign of its wisdom and those who see it as the dead hand of the past. At stake is also a longer conflict about whether U.S. history is a matter of great changes or a changing sameness.

The terms of the revived debate today began to take shape in the early twentieth century, when a chorus of self-styled Progressives called for major policy changes to redress structural inequalities and rampant corruption. Though accused of being radical, and often moralistic, they were also professionals in their various fields, well-meaning, and not least burdened by a sense of guilt at their personal good fortune after a series of national economic downturns. They sought to use the tools of modern social analysis and science to create better government. In the young disciplines of history and political science, one of their controversial avatars was a Midwesterner and Columbia professor named Charles Beard, who in 1913 more seriously pursued the suggestion of an earlier scholar, Orin G. Libby, that perhaps the framers of the Constitution had been an alliance of commercial classes more than a virtuous convocation of statesmen. Beard pushed the class analysis even further, depicting the framers as a self-interested clique of bondholders. The implications were obvious. If the Constitution fashioned in 1787 primarily served the class alliances of its time and its authors, then its institutional apparatus could be tinkered with or even thrown aside as decrepit in its very mode of operation as well as its unfortunate results. (It was not a coincidence that the years between 1913 and 1920 saw constitutional amendments permitting the income tax, establishing the direct popular election of U.S. senators, and female suffrage.)

The backlash to Beard helped send an Ohio newspaper editor and former lieutenant governor named Warren G. Harding to a Senate seat and eventually the White House in 1920. Harding’s headlines screamed about Ivy League professors tearing down the “Founding Fathers,” a term he tried out in a subsequent speech that stuck long after its politicized origins were forgotten. The fact that Harding’s own administration reached heights of corruption not exceeded until Donald Trump has never given those who still refer to Founding Fathers any pause.

Despite the backlash in the political realm, Progressive approaches to history, including critical approaches to most of the American past, dominated younger and intellectual circles for a generation, surviving in the work of historians like Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. (and his son, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.). It helped, as Staughton Lynd later pointed out, that Beard and his followers did little to question what Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois famously called “the color line.” Their great battle was between partisans of “the people”—usually farmers but sometimes including their urban working-class allies—and vested interests: businessmen, bankers, capitalists. In this scheme, slaveholding Southern planters and their descendants might be relied upon to lead yeomen (small property holders) against the capitalists.

But the intellectual prominence of the Progressives finally faded, too, beginning in the 1940s. In the middle of a burgeoning Cold War, it proved useful to see the American past as a story of well-meaning colonists taking up arms against the dominant empire of their day, especially as the United States seemed to be on the rise, not falling into corruption or decline. From this perspective, it was the Americans, including the framers of the Constitution, who were provincials, the colonized rather than colonizers, the underdogs who got out from under British dominance. Their financial interests and elite status didn’t matter so much, or even at all. Maybe they even saved the West and its traditions from corruption and imperial overreach.

Anti- or post-progressives thus found that they could have their Americanism and their critique of their colleagues’ Euro-snobbery (whether from the left or the right) at the same time. Ever Oedipal, young historians began to make their name by attacking the pieties of their Progressive forebears. (Not coincidentally, the U.S. academy at this time was growing by leaps and bounds: the generational critique proved fertile soil for career advancement.) The Progressives had been like the Populists, the argument went—their lame, homegrown quasi-socialism exposing them to be provincial rubes and fellow-traveling ideologues at once. The American Revolution and the Constitution were, in fact, worthy of celebration. Criticizing them as antiquated or bourgeois now seemed counterintuitive; they were valuable precisely because the nation hadn’t fallen into one –ism or another. The truths were held self-evident again.

The strength of this kind of history of the American Revolution, as its foremost practitioners Bernard Bailyn and his student Gordon Wood never tired of telling us, is that it has understood its prime movers, who they began calling “the founders,” on their own terms, which means examining their particular worldview sub specie aeternitatis rather than judging it as primitive and lacking or as propaganda, containing seeds of bias or oppression—the cardinal sin of Beard, in their judgment. This worldview could be called ideology—Bailyn’s most famous book traced The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967)—but even as such it was the key to understanding their motives and the reasonable, not regrettable, outcomes. By the late 1980s Bailyn and his students had stopped using the word “ideology,” as by then it smacked too much of critique.

In his new book, Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism in the American Revolution, Wood insists that Beard still “casts a long shadow.” The same could be said of Wood, who has been an authority on this subject for almost as long as the fifty-six years that elapsed between Beard’s Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913) and the publication of Wood’s first book, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787, in 1969. That study won acclaim for highlighting the intellectual and practical dilemmas of republicanism and for seeming to split the difference between celebration and criticism of the founders. Wood argued that, ironically, the course of the 1780s led toward a Madisonian “science of politics” that sought to bury economic conflict in schemes of federalism and representation, and did it so successfully that it created an American political tradition that couldn’t deal honestly with class or money.

In this, the young Wood performed a scholarly triple axel. At great length and sophistication, he had offered something to those inclined to celebrate the Constitution, those who criticized it, and those looking for some way between. The republic, simply put, was moderate yet innovative, advanced yet caught up in self-deception. Expecting the founders to have dealt with something as modern as race relations, however—as Lynd, New Left–affiliated historian and activist, was doing in the late 1960s in essays that laid out precisely where the Progressive historians had failed—was “anachronistic.” Thanks to his outspoken antiwar activism, Lynd lost his job at Yale. For his part, Wood got tenure at Brown, and after winning a Pulitzer for his second book, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1991), he became known for complaining publicly about his left-leaning and multiculturalist colleagues and for the plaudits he received from Newt Gingrich, who distributed the book to rookie House members. That wouldn’t have been so notable or memorable had it not been part of what New York Times Magazine editor-in-chief Jake Silverstein, in a lengthy new response to the controversy over the 1619 Project, rightly describes as an earlier iteration of today’s outrage—one that targeted the first set of national guidelines for teaching U.S. history and was cooked up just in time for 1994’s midterm elections.

Wood laid a foundation for a distinctive—we might say strategically sophisticated—kind of “founders” history, one that keeps a quiet distance from uncritical flag-waving by emphasizing at every turn how different the eighteenth century was yet also embraces patriotism by insisting that everything good about the United States still somehow emanates from the founding, even if sometimes ironically and unintentionally. Criticisms from the left—by neo-progressives or multiculturalists who would add other groups to the pantheon of founders, or would emphasize or even dwell at all on the antiquated, racist, inegalitarian aspects of what the founders created—have been mocked by Wood, in prefaces and footnotes and occasional book reviews, as misguided, “presentist” Beardian holdovers. That’s the language he uses when he is being polite. On other occasions, Wood descends into explicit red-baiting, as in his reviews of The Unknown American Revolution (2005), the career-summing work of the late Gary B. Nash that Wood tars as “locked into . . . Marxian categories,” and Robin Einhorn’s American Taxation, American Slavery (2006), a brilliant and meticulous excavation of tax policy’s links to the peculiar institution. By losing focus on “revolutionary characters” and their leadership, Wood has charged, these historians are doing politics, not history. How he has chosen to summarize his life’s work in his latest book tells us a lot about the current debate over the Constitution and where the current threat to his would-be vital center—his conviction that in the United States “power and liberty” have flown evenly and together—comes from: the claim that racial oppression has been a primary and continuous force in U.S. history, one reinforced, rather than mitigated, by the founders’ Constitution.

Wood begins with Tom Paine, who used to be exiled from the elite pack of founders for being too radical and plebian (not to mention his shilling for the French Revolution). Wood writes that Paine left Britain in 1774 “full of rage at the decadent monarchical society that had kept him down” and fully “ready to articulate America’s destiny.” What he means is Paine’s suggestion, in Common Sense (1776), that a new United States should throw over not just the monarchy but all the old laws. For Wood, the essence of the American experiment lay in a constitutional process that leads to fundamental laws that have popular sanction. The Founding—the real American Revolution—wasn’t a war for independence or even the Constitutional Convention: it was the process. Because the United States lacked an “ethnic basis for its nationhood,” Americans came to look to founding documents and principles as the “source of our identity.” Several complicating facts—that the English thought of themselves as uniquely bound by laws, that many colonists came to identify strongly as British before the Revolution, and that for a decade they asked for better representation in Parliament or for the King to simply listen to their petitions—no longer much interest Wood, at least when they get in the way of emphasizing that “never in history had there been such a remarkable burst of constitution-making.”

Paine is now Wood’s prophet precisely because it is Paine who first emphasized the American Revolution as an opportunity “to begin the world over again.” Again and again, Wood elevates the United States to unparalleled significance in world history. The exceptionalism here is not even thinly veiled; what to Paine had been propaganda and exhortation in Wood becomes a statement of fact. Paine, at least, felt constrained to make some actual comparisons. Not Wood: he simply and uncritically presents Paine’s resentful image of a decadent empire. It is the ultimate straw man, mirroring the selective memory of the American revolutionaries themselves, who stressed how faithful they were to English traditions and laws—until they weren’t.

The notion of an absolute difference between Britain and America—the essential premise of all revolutionary wartime propaganda—undergirds Wood’s description of the imperial controversy. In his telling, while the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) left the British empire suddenly sovereign and dominant over half of North America (something numerous native nations effectively disputed, but that’s irrelevant to Wood), colonial life had led Americans to understand representation as direct, local, and real rather than as an abstract mediation through the king or members of parliament elected by a small number of constituents. Faced with new taxes they didn’t vote for, colonial spokesmen tried to finesse the issue by distinguishing internal and external taxes, or taxes versus other kinds of laws. Key imperialists, however, discerned that the real issue was sovereignty, and not just what parts of it resided with the king or parliament. After a decade of activism and reaction, colonial arguments drifted, by 1774, toward invocations of natural rights, which had the radical potential Paine recognized as a world-shattering event, even “the cause of all mankind.”

Thus we come to one of the climaxes of the book. Wood can’t emphasize enough how radical the Declaration of Independence was in 1776. In another of his many superlatives (of the kind one imagines most professors excising in red on an undergraduate paper), the Declaration becomes the “most important document in American history.” This is a fine tautology, perhaps, if your goal is to stir up swoons of national pride, but analytically, of course, the statement means next to nothing. This kind of language says more about Wood’s aspirations for U.S. history—the story he wants to tell about the one true meaning of America, the American identity he himself wants to embrace, the inspiring transition from Old to New World—than the history itself. Again and again, Wood invents a radicalism that is about anything but nationalism and everything but material interests—all in the name of doing history rather than politics.

That radicalism plays directly into Wood’s concise summation of his earlier arguments about the new state constitutions following 1776. In this account, the Americans practically invent the notion of written constitutions as fundamental law, to the extent of establishing, as Paine had forecasted, intermediate elected bodies (conventions) to write them and special elections to ratify them. These constitutions dismantled executive power, isolated and lessened judiciary powers, and empowered legislatures as the most representative and democratic part of government, while tentatively moving toward bicameralism as a check against democratic excess.

Nevertheless, the federal structure that barely got the new nation through the war was not up to coordinating these thirteen newly empowered states in a hostile world. Wood pivots from emphasizing the weakness of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of taxation and foreign affairs to the old Madisonian saw that the very legislatures he had praised as revolutionary had indulged in “excessive democracy.” Wood isn’t simply saying that Madison saw it this way, and that that is why he developed a science of government around fears of majority tyranny and mechanisms for balance—an account that is true enough, and indeed represents the scholarly consensus. Wood is saying there really was too much democracy in the American Revolution.

On this point, Wood predictably fails to engage the work of Woody Holton, Barbara Clark Smith, and Terry Bouton, who argued convincingly, in three important books published a dozen years ago, that the political crisis over taxation in the 1780s reflected less demagoguery than profit-seeking by a threatened gentry class of mushroom patriots who no longer worried much about the inflation-driven travails of their neighbors. Progressive history got a lot more careful and convincing in this third, twenty-first century wave, but Wood has ignored all of it. Instead he doubles down on his argument from his 1991 study, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, that the financial crisis of the 1780s was caused by ordinary people seizing the democratic desire to “get rich” (he sees capitalism and democracy and the middle class as ultimately the same things, none of which had anything to do with the South or with slavery). If the first wave of Progressives made the (white) people perpetual victims of greedy elites, for Wood they are always already “middle class.” In this, Wood uncritically reproduces the views of elites like Madison, who to him are always the best witnesses—sometimes charmingly candid, often amusingly jaded, but rarely self-interested, and never themselves operating as anything resembling a class. Even to suggest such a thing amounts to treason.

After this accounting, it is hardly surprising that Wood objects to the title of Michael Klarman’s comprehensive tome The Framers’ Coup (2016), as he does in a footnote, because it “suggests a degree of skullduggery on the part of the framers.” Yes, Wood admits, the Constitutional Convention was stacked with nationalists and involved striking, if ambiguous, compromises between federal and state authority; yes, the debates over ratification reveal (unnamed and uncharacterized) “social division.” But the important thing is that the results created “an entirely new intellectual world of politics” that grounded representation in the sovereignty of the people, not estates or classes tied to the separate branches. The federal Constitution, in other words, took what was good and stable in the state constitutions and left the dangerous democratic tendencies out.

Wood’s insistence on interpreting everything to the founders’ credit, even against his own evidence and every possible counterargument, comes to a head in his fifth chapter. In Power and Liberty’s introduction, Wood admits, for the first time in his many books, that slavery was “one of the major issues” in the convention and in the ratification debates. Yet he makes this claim only to justify segregating slavery into a separate chapter in which he contextualizes the subject into irrelevance. Slavery is apparently still beside the point because, as his mentor Bailyn stressed, the important thing is that the Revolution made slavery a problem: revolutionary ideology “created” and “galvanized” an antislavery movement. Missing from this account—as well as all of Wood’s earlier accounts—are the pre-Revolutionary Quakers who actually did the first effective organizing, their English allies, and the enslaved people whose travels and resistance created a cohort of emancipated spokespersons like James Somerset (who ran away from his customs officer enslaver and catalyzed Lord Mansfield’s 1772 decision in Britain that posited slavery as inferior colonial law), Phillis Wheatley (who made pointed public criticisms of slaveholder hypocrisy), and the first black abolitionist activist, Olaudah Equiano (who fought in the Seven Years’ War, not the American Revolution).

The Somerset case, Wood concedes, may have caught the attention of the enslaved—Wood’s first-ever concession that they had a politics—but the patriots weren’t the slightest bit worried about it. To Wood, it’s inconceivable that his heroes kept quiet about things they didn’t want their slaves to know about, or that they were trying to spin the slavery question that was already being thrown in their faces. Independence was inevitable already in 1775, so defending property in slaves against military threats in 1775 and 1776 couldn’t have “forced founders” in Virginia and South Carolina to support independence, as Holton argued in an important study two decades ago and reiterates in his new book, Liberty Is Sweet.

Instead, Wood writes, the American Revolution inspires emancipation all over the new world as “the first great antislavery movement in world history.” The founders, on this telling, really were antislavery; the ways the Constitution hard-wired slavery into the new order were a tragic accident of well-meaning statecraft. In Wood’s account, our revered statesmen mostly believed that it would die a natural death anyway. Not coincidentally, this chapter on “Slavery and Constitutionalism” dispenses with the Constitutional Convention and the ratification debates, already covered in slavery-free detail in the previous chapter, in just three and a half pages. The main point is that the three-fifths clause “seemed a necessary compromise”—at least to the ultimate authority, James Madison. Astonishingly, Wood has moved from insisting defensively, for decades, that slavery didn’t matter because the founders didn’t talk about it, to saying that it isn’t very important because they thought they had sufficiently dealt with it. The thread tying together these otherwise inconsistent positions is Wood’s fundamental insistence that the great men of the American Revolution be let off the hook. Slavery can be an issue so long as it makes clear that the Founders were noble.

Having dispensed with slavery and racism as holdovers of the ancien régime, Wood devotes two more chapters to the healthy effects of the constitutional settlement. Out of the separation of judicial powers, Americans groped toward a role for judges as the new disinterested aristocracy that would preside not simply over justice, but over “constitutional law,” considered as foundational yet also as written statutes. At the same time, judge-interpreted laws placed legal boundaries around property and contracts. Wood is startlingly certain that the results have been essentially positive and distinctively American (even though Britain’s Mansfield and his protégé William Blackstone actually pioneered the sanctity of contracts, including financial instruments like maritime insurance). There has been “nothing quite like it anywhere else in the world,” Wood writes, again forsaking careful scholarly comparison for transparent nation-bragging. Where capitalist modernity can’t be reduced to American constitutionalism, Wood resolves to stress its ultimate compatibility. His final chapter relates the emergence of distinct public and private realms, or the separation of politics and social authority, which he construes, contra reams of twenty-first century scholarship, as having nothing to do with patriarchy, Western tradition, capitalism, or the desires of slaveholders to protect what they would come to call their “peculiar domestic institution.”

Despite the intellectual favor it won more than thirty years ago, today Wood’s anti-Beardian celebration of founders backing their way into modernity seems absurdly tone deaf as well as factually dubious. His confident celebration of the judiciary at a moment when public confidence in the Supreme Court (not to mention law enforcement) may be the lowest it has been since none other than the Progressive Era seems at best a tinny echo from the past, at worst the unfortunate result of the praise he has received over the years from law school professors who can agree only on that one thing: constitutionalism as the American Way. That slavery and the enslaved hang in the middle of this book, separated but hardly equal, unconnected to anything else in history or constitutionalism, is a potent reminder of just how snow-blinded mainstream American scholarship can be even when it thinks it is recognizing the presence of Black people. In the end, for all the veneer of sophistication, Wood merely ratifies the perspective of the Founders, whose words he privileges. They were embarrassed by slavery; they wanted to portray it as not really American, as an exception, fated to end, a separate Southern subject given a mere last lease on life by a necessary compromise. Wood does too. It’s the ultimate in winners’ history, and all the more so when Wood defends it as just the facts, told “as impartially and as truthfully as possible,” rather than—God forbid—a “usable past.”

Carol Anderson’s take on the legacy of the Constitution is as good a measure as any of the rise of a different view, aspects of which have been present all along but which turn both Wood and Beard on their heads. In this telling, American history is characterized by a different set of continuities than middle-class democracy or class conflict. Constitutionalism still structures our history and politics, but in ways that are more revealing and disturbing than ever, because in the Constitution we can see not just compromises over the entrenched institution of slavery but an uncompromising core of anti-Blackness. There is little progress, less irony, mostly tragedy. Where Wood casts the Founders as inhabitants of a distant world, for Anderson they are modern, all too modern.

Anderson’s new book, The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America, is the third of a trilogy, coming after pithy long views of White Rage (2016) and of disfranchisement in One Person, No Vote (2018). With each volume, events that followed have seemed to prove her prescience, leading her to elaborate in this latest volume a view of the Second Amendment that had been broached before by Robert J. Cottrol, Raymond T. Diamond, and Carl Bogus but nevertheless is not very widely known. Anderson starts from evidence pulled from news articles about the violent deaths of armed but peaceful Black men and women like Philando Castile as opposed to the fate of gun-toting rebels like Cliven Bundy. Again and again, a double standard emerges. When Black people have guns, possession is not a right to protect: it’s a threat that gets them shot. Anderson insists that we face a paradox in the history of the Bill of Rights and its enforcement. Whatever their original intentions, protections offered by amendments to the Constitution, such as those for equal protection under the law and voting rights or those against “cruel and unusual punishment,” have often been weakened in order to undermine Black rights, even when the original intent was otherwise. The “fatal” Second Amendment, by contrast, has been strengthened for everyone but Black people.

This is why Anderson argues that the well-worn debate about whether the Founders meant to enshrine the right of individuals or collectives (i.e., state-sponsored militias) to bear arms is a red herring, “distracting” us from the way the amendment was and still is wielded as an instrument of racial hierarchy. She’s very clear: the Second was “designed,” “constructed,” and “consistently” applied against people of African descent, before and after emancipations that might seem to have changed their status, before and after the later amendments that supposedly guaranteed their civil rights. She allows the possibility that other amendments could again be a pathway to “civil and human rights,” but not the Second. Here, original intentions and hundreds of years of history create an ever-renewable tool of oppression. When Black people have guns, while it might be better than not having them, it gets them in trouble. When white people have guns, it doesn’t. When both have them, as in confrontations with police—even Black police—the results are predictable. Anderson doesn’t mention that most gun homicides are intraracial, or that the Second Amendment couldn’t itself militarize today’s police with leftover ordnance, because to her guns aren’t “the key variable here. It’s Black people.” The Second Amendment has been “quicksand for African Americans.” She suggests that anti-Blackness feeds an obsession with the Second in white culture that has made it an infinitely renewable resource, regardless of the aggregate effects of lax gun laws. This may not be Afro-pessimism, but it certainly is a thread of Black originalism.

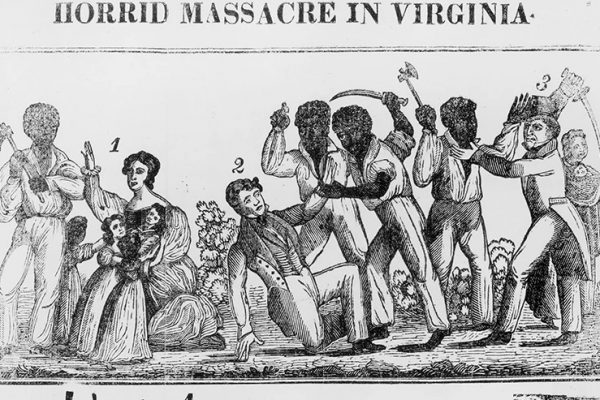

Anderson spends more time on the colonial period than Wood, thanks to her stress on continuity over revolutionary change. Slave resistance and revolts led to laws that restricted gun ownership for Black people, whether free or enslaved. If she exaggerates the organization and arms of the early Virginia militia, she is on well-established ground when she describes the emergence of slave patrols as versions of militia and as arms control measures for “suspect groups” like Natives and Africans. She’s devastating on the consequences of the American Revolution, where she follows both classic and recent historians such as Benjamin Quarles and Robert Parkinson in seeing a process by which Black American support for the patriots in some quarters was overwhelmed by the British recruitment of the enslaved in the South. As Blacks became known as a fifth column, disarming them became a patriotic duty.

Anderson also sees the Deep South coming to the Constitutional Convention with the single-minded desire to protect slavery. This overstates the case, and makes it a bit harder to understand the actual dynamics that, as Anderson argues, strengthened the government for some of the slaveholders’ purposes while weakening it in telling other ways. While South Carolinians bargained successfully to protect slavery, during the debates in the states over ratification some antifederalists like Patrick Henry in Virginia depicted the new federal government as a threat to local militias that kept slaves in check. The Second Amendment, she contends, amounted to a “bribe” designed to buy off southern and antifederalist critics of central state power, a bribe “steeped in anti-Blackness.” What Anderson can’t prove using the kind of evidence Wood elevates above all—direct statements of intentions by Founders—she shores up by brilliantly suggestive readings showing how the Bill of Rights, the Second Amendment at its core, elevated the overall importance of militias, whose main (and mainly effective) role between wars was to keep down Blacks and create a bulwark against federal interference in the states.

The American Revolution, then, wasn’t about natural rights, much less about abolition. It didn’t inspire “all our current egalitarian thinking” (as Wood insisted in Radicalism), but more of the opposite: a backlash. Anderson finds plenty of evidence in the early republic that makes gradual emancipation in the North look like surface, feel-good reform, not the world-historical event presaging equality that Wood and many other historians see. The Naturalization Act of 1790 granted citizen status explicitly and solely to white immigrants. The 1790s Uniform Militia Act made every white able-bodied man subject to militia duty and required them to possess arms, in effect nationalizing the whiteness of guns. Anderson sees an early-emerging pattern of light punishments for white rebels in the cases of Shays’ Rebellion and the Whiskey Rebellion but overwhelming force used against enslaved freedom fighters. The comparison may not be quite right, because white protesters—calling themselves regulators, not rebels—didn’t have to exert as much violence as enslaved rebels, who fought for their lives. Still, the trend is telling. Even when Black people took up arms for the republic, as with the freemen of color militia in New Orleans who fought with General Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812, or with the approval of local communities, as in important instances of violent resistance against slave catchers, the result merely “gave the illusion of a right of self-defense for Black people.” The key variable, again, wasn’t any individual or collective right to bear arms, or a conflict between two meanings of the Second Amendment: it was anti-Black racism.

Even the Civil War didn’t undo this enduring core of racism. Anderson cites Kellie Carter Jackson, whose Force and Freedom (2019) offers the most systematic study to date of how Black abolitionists dealt with the question of violent means. “The core of white supremacy was not chattel slavery,” Jackson writes, “but anti-blackness.” This claim can sound like a tautology—racism derived from racism—until we realize the limits of the counterargument, on which much of the antislavery political tradition rested, was that slavery, inherently immoral, was the problem and its end, gradual or immediate, the complete solution. Where historians like Du Bois and Eric Foner have stressed a glass half full during Reconstruction—when Black individuals and communities successfully defended themselves to the point (and necessity) of parading regularly with rifles—Anderson asks us to reflect on the extreme backlash, justified by President Andrew Johnson and epitomized by occasions in South Carolina and Louisiana when Blacks shooting guns at white Klansmen and rioters led to full out massacre—of Blacks. To Anderson, there is a straight line from the Klan-led Colfax Massacre of 1873 to the dishonorable discharging (and thus disarming) of Black U.S. soldiers in Brownsville, Texas, in 1906 to the controversies around policing today, where the double standard of Second Amendment enforcement, more than the police power itself, becomes fatal. She doesn’t have to invoke lynching as a reality or a metaphor because the gun double standard has been more pervasive and continuous. The Second becomes just as central to the anti-Black political order today as the Three-Fifths Compromise was during the age of slavery.

Anderson doesn’t tell the whole story of the Second Amendment: her account of its origins and uses is a polemical corrective, not the last word or the balanced account that Noah Shusterman provided in Armed Citizens: The Road from Ancient Rome to the Second Amendment (2020). Once we see the militia as shock troops of slavery and Jim Crow, though, it is hard to take as much inspiration from fears of the kinds of standing armies which in Black American history have on more than one occasion been a liberating force.

This story will be tough to swallow for those who reject what James Oakes calls the new “racial consensus history,” according to which racism not only runs deep in the American grain but is its actual DNA—a metaphor Nikole Hannah-Jones used in her lead essay to the Times’s 1619 Project and which Anderson employs once in an aside. The critics of racial consensus history insist that this isn’t history at all: it ignores any change, and is sure to be politically debilitating. As Matthew Karp recently lamented in Harper’s, “Progress is dead; the future cannot be believed; all we have left is the past, which must therefore be held responsible for the atrocities of the present.” (Never mind that Hannah-Jones herself insists on change: “black Americans have made astounding progress,” she wrote in her 1619 Project contribution, “not only for ourselves but also for all Americans.”)

This is often a critique from the left, very different from Wood’s selective evacuation of the present and all politics from his account of an ancient founding that ironically leads to an implicitly white middle-class modernity. It suggests, however, that progressive history, not to mention progressive politics, may be as much in thrall to narratives built around revolutions as is founders history à la Wood. Karp rightly complains that origins stories—whether about 1619 or 1776—are being asked to carry too much political weight, but pointing to the Civil War or the civil rights movement as the real American revolution does not solve the problem. In a Public Books essay criticizing Walter Johnson’s emphasis on continuities in his recent history of St. Louis, The Broken Heart of America, Steven Hahn tries to find a middle ground by arguing that “history can be about continuities but it is also about change, and analytical concepts are useful to the extent that they can account for and incorporate change.” What this misses is that some concepts, like race itself, are precisely about how some people have made history by denying to others the possibility of change. Accounts of history that stress continuity aren’t necessarily bad history. They’re just unsettling, especially if the past is full of bad stuff that can’t be recycled as the noble source of our political system, national identity, or reform agendas.

Where does this debate leave us? Saying that good history has to reveal change or progress in the nation is just as risky as saying the past has no relation to the present. Much can be explained by an American history that instead stresses revolutions and reactions. Indeed, the fact that backlashes happen repeatedly suggests that American revolutions aren’t all they’re sometimes cracked up to be. It may be time to admit that our tendency to think of revolutions as epochal transformations, rather than as circular turns, has not been conducive to understanding the power of racism’s repeated reinventions, which not a few have echoed Amiri Baraka in calling the “changing same.” We can recognize these cyclical processes without succumbing to them; doing so might even help us see how persistent injustice works differently today.

Anderson’s work clears an opening for a more cyclical, longer view of struggles and backlashes than is possible in histories that see the Civil War as the more revolutionary American Revolution or, in Foner’s words, our “Second Founding” (a view that Beard pioneered). In the United States as elsewhere, revolutions and civil wars have enslaved as well as liberated. For all their radicalism, they have consistently led to backlashes, sometimes in the form of new constitutions. At the same time, saying that racism is the fundamental fact of U.S. history will not supply a political strategy for the present any more than stressing capitalism, conflating racism and capitalism, or ignoring both. Its virtue is to correct the errors of fact and focus that, in Wood’s histories, leave us strikingly unable to see how we got where we are.