This essay appears in print in Is Equal Opportunity Enough?.

In June 2020 Donald Trump tweeted, in characteristically hyperbolic style, that his administration had “done more for the Black Community than any President since Abraham Lincoln.” First in the list of his putative achievements were Opportunity Zones (OZs), a stealthy provision of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 that offers capital gains tax reductions in the name of incentivizing investment in “low-income” regions and “distressed communities.”

At a number of rallies that summer, Trump went on to claim—without evidence—that thanks to OZs, “countless jobs and $100 billion of new investment . . . have poured into 9,000 of our most distressed neighborhoods anywhere in the country.” (Estimates of the actual amount of investment are lower.) Trump also lauded the program in his State of the Union address earlier that year, claiming that “wealthy people and companies are pouring money into poor neighborhoods or areas that haven’t seen investment in many decades, creating jobs, energy, and excitement. This is the first time that these deserving communities have seen anything like this.”

The OZ initiative starts from the premise that communities are distressed because of a lack of private investment and that tax policy offers an easy solution. As the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)—a think tank established in 2013 to promote this view—puts it, “the tax code should encourage private investment in communities that are struggling to attract capital, create jobs, and lift residents out of poverty.” The incentive under the Trump tax bill applies to taxpayers who make a qualified investment in a Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF), which in turn must invest at least 90 percent of its assets in a designated OZ. QOFs operate as investment vehicles, organized as corporations or partnerships. A variety of entities have established or invested in QOFs, including real estate private equity firms, investment banks, supermarket chains, and hedge funds. To qualify as an OZ, a census tract must be either a low-income community—with a poverty rate of at least 20 percent, or a median family income of no greater than 80 percent of the state’s median income—or contiguous to one. States could nominate up to 25 percent of their low-income communities, and the year after the bill became law, U.S. Treasury officials certified 8,764 nominations, amounting to about 10 percent of all tracts in the United States.

There are three key tax advantages associated with the program. First, investors can defer paying taxes until the end of 2026 if they place capital gains they have realized elsewhere into a QOF—amounting, in effect, to an interest-free loan. Second, taxes on those gains are reduced depending on how long investors keep their assets in a QOF: 10 percent for five years, 15 percent for seven years. Third, investors can avoid paying any capital gains taxes whatsoever on gains that are realized from the QOF itself if the investment is held for a decade.

The scheme may sound attractive: What could be so bad about giving the wealthy an incentive to pour money into impoverished neighborhoods? But contrary to Trump’s breathless claims, a mounting body of evidence shows that OZs simply don’t work—at least if the goal is to help lift low-income communities out of poverty rather than redistribute wealth upward, subsidize luxury real estate development, and facilitate gentrification.

In fact, the idea that tax breaks can help revitalize distressed communities has a long history, one that stretches back to the early days of the neoliberal revolution in the United Kingdom. The scheme was imported to the United States by conservatives and eventually won bipartisan support in the 1990s, but the strategy didn’t work in the UK, and it hasn’t worked here. Contrary to the hopes of the Biden administration and a bipartisan group of reformers in Congress, Trump’s overly lax program cannot be salvaged with better reporting and oversight. Addressing place-based deprivation requires a different approach all together—one that empowers communities and local governments rather than seeks to court private investors.

The proximate origins of OZs can be traced to billionaire Sean Parker—Napster co-founder, the first president of Facebook, and a former board member of Spotify. As Parker explained in 2018, he wanted to find ways to encourage investors to channel capital gains into run-down areas. “People were sitting on large capital gains with low basis and huge appreciation,” he said. “There was all this money sitting on the sidelines. . . I started thinking: How do we get investors to put money into places where they wouldn’t normally invest?”

As journalist David Wessel vividly details in his book Only the Rich Can Play (2021), Parker along with fellow investors used $8.5 million to bankroll EIG and recruited bipartisan leadership. Steve Glickman, a former senior advisor to President Barack Obama, and John Lettieri, former aide to Republican Senator Chuck Hagel, joined Parker as co-founders, while Kevin Hassett, Trump’s chief economist, and Jared Bernstein, who held the same position for then-Vice President Joe Biden, served on the economic advisory board. (Bernstein has since joined Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers; Biden recently nominated him to be its chair.)

In 2015 Hassett and Bernstein wrote an EIG brief outlining key underpinnings of the OZ idea. Noting that “a very large stock of savings in the form of unrealized capital gains has built up in recent years,” they called for incentives that would establish “a new equilibrium where investors flock to distressed areas because they are confident that other investors will as well, then the investments will also have the potential to be highly profitable, which would feed a virtuous cycle.” Such a program, they argued, would “partially address widening inequality and lack of economic mobility in targeted areas, but do so in a manner that relies on markets and new enterprise to help the poor.”

A legislative breakthrough came when Senators Tim Scott (Republican of South Carolina) and Cory Booker (Democrat of New Jersey) drafted the Investing in Opportunity Act in early 2017, but despite the bill’s fourteen co-sponsors in the Senate, House Speaker Paul Ryan had doubts. Trump, too, had little interest at first, but things changed after his incendiary remarks about a white nationalist protest in Charlottesville in the summer of 2017. According to Wessel, Scott met with Trump and urged him to help undo the PR damage by backing OZs. With Trump onboard, Ryan’s opposition faded, and the bill was inserted into the reconciliation bill that won congressional approval in December 2017.

Far from a truly innovative program, however, opportunity zones are an old idea—and the history tells a cautionary tale. The basic idea first emerged in the UK in the 1970s amid serious concerns about the deterioration of British inner cities. The devastating effects of deindustrialization were compounded by the stagflation that bedeviled both left and right governments since the late 1960s. It was in this context that urbanists and politicians cast about for alternatives to Keynesianism.

One proposal came from Sir Peter Hall, a geographer by training, who lamented the moribund state of Britain’s great cities. In a 1977 speech to the Royal Town Planning Institute, Hall argued that the revival of urban areas required a dose of “fairly shameless free enterprise.” Inspired by the meteoric rise of cities like Hong Kong and Singapore, Hall’s “freeport solution” envisaged “free zones,” which would lie “outside the limits of the parent country’s legislation”—free from taxes and regulations and where “bureaucracy would be kept to an absolute minimum.” As Hall later acknowledged, the speech reflected his “blue sky” thinking and was made “slightly tongue in cheek.” As such, he “did not expect anyone to take this seriously in policy terms.” He was therefore very surprised to receive a call from Geoffrey Howe inviting him to lunch.

Unlike Hall, who hailed from the left, Howe was a key member of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party shadow cabinet. Once he became chancellor of the Exchequer in 1979, Howe launched a neoliberal transformation in British economic policymaking with the introduction of monetarism, tax cuts, and deregulation. What united Hall and Howe was their common concern with urban woes and a shared commitment to using neoliberal techniques to ameliorate them. Although Howe was concerned about British cities in general, he was especially keen to arrest the decline of London’s docks. Indeed, Howe chose the Waterman’s Arms—a pub on the Isle of Dogs in the heart of what became known as Docklands—to give a “major speech” in 1978 on the deleterious state of British cities. As he puts it: “There, in the midst of dockland dereliction at its most depressing, I launched the idea of Enterprise Zones.”

In a classic statement of what would become neoliberal orthodoxy across the globe, Howe blamed regulation and taxation for Docklands’ decline, arguing that the region’s “urban wilderness” represented the “developing sickness of our society” in which “the burgeoning of State activity now positively frustrates healthy, private initiative, widely dispersed and properly rewarded.” For Howe, the “frustrating domination of widespread public land ownership and public intervention into virtually all private activities has produced a form of municipal mortmain which will not be shifted without a huge effort of will.”

In Howe’s view, the only cures were to be found in “fundamental reform of our tax system”—he meant tax cuts—and “the sensible deregulation of our economy.” And while Howe (like Thatcher) sought to apply this formula for the British economy writ large, he recognized that it would take time to accumulate the necessary political capital to transform the entire British economy in the neoliberal image. Still, in Docklands he saw a unique opportunity for a quicker transformation. Enterprise zones, as he put it, would “go further and more swiftly than the general policy changes that we have been proposing to liberate enterprise throughout the country. . . . the idea would be to set up test market areas or laboratories in which to enable fresh policies to prime the pump of prosperity, and to establish their potential for doing so elsewhere.” The introduction of enterprise zones was not only a way of “trying out our ideas,” Howe thought, but also a “kind of trial run intended to foster support for the other possible changes, which we sought to introduce more broadly in the British economy.”

Having convinced Thatcher of the efficacy of enterprise zones, Howe included them in his 1980 budget “with the intention that each of them should be developed with as much freedom as possible for those who work there to make profits and to create jobs.” Ultimately the conservatives enacted eleven enterprise zones, with the most prominent located in the Isle of Dogs. Besides enjoying 100 percent capital allowances for both industrial and commercial buildings—meaning that the total costs of new buildings could be deducted from taxable profits—companies in the zones would see complete relief from development land taxes, ratings, industrial training certificates, and levies and a drastically simplified planning scheme.

The idea would not stay put. Across the Atlantic, enterprise zones soon caught the attention of Stuart Butler of the Heritage Foundation and Congressman Jack Kemp, Republican of New York who championed Ronald Reagan’s tax-cutting agenda.

Butler thought the causes of urban decay in the UK and the United States were “sufficiently similar to allow possible solutions voiced in Britain to be given serious consideration in the United States.” He concluded that enterprise zones would go some way toward solving the “urban crisis” that plagued U.S. cities. His conviction was that slashing taxes—and, where possible, regulations—would encourage the development of small business, which he viewed as critical for urban revival. For his part, Kemp—like Hall and Howe—was inspired by the rise of Hong Kong, which he characterized as “free-trade zone, free-banking zone and a free-enterprise zone.” The key to emulating Hong Kong’s apparent success, Kemp thought, was to use cuts to capital gains taxes to unleash untapped entrepreneurial potential. (As historian Macabe Keliher has noted in these pages, Hong Kong has long played a central role in the neoliberal imagination—Milton Friedman, for example, thought the city showed “how the free market really works”—but the social consequences of policies there have been “disastrous.”)

Kemp and his fellow enterprise zone enthusiasts introduced over twenty bills in the House and Senate during the 1980s. These bills commonly included reductions to capital gains and business taxes, regulatory relief, and accelerated depreciation. Notably, in a memo to Reagan, Kemp argued that enterprise zones would bolster urban support for the GOP: “I obviously believe that enterprise zones are good public policy. But they are also good politics . . . Enterprise Zones can be a symbol—Ronald Reagan’s symbol—of hope that the Republican Party will not concede our nation’s poorest communities in its attempt to become the majority party.” Reagan was convinced. He asked Congress to help “communities to break the bondage of dependency. Help us to free enterprise by permitting debate and voting ‘yes’ on our proposal for enterprise zones in America.”

Although enterprise zones enjoyed the notable backing of the White House, most Republicans in Congress, and a smattering of Democrats, the federal initiative was stymied by key Democrats in pivotal positions. Among them was Chairman of the House Ways and Means committee Dan Rostenkowski, who remained unconvinced for most of the 1980s. Nevertheless, enterprise zones proliferated at the state level, propelled by a growing cadre of backers at the Heritage Foundation, the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Cato Institute, and the Sabre Foundation. As Karen Mossberger demonstrates in The Politics of Ideas and the Spread of Enterprise Zones (2000), by the end of the decade over forty states had their own enterprise zone programs.

Democratic skepticism wouldn’t last in the face of these inroads. By the 1990s Democrats such as Charles Rangel—who had voted against several enterprise zone bills the decade before—introduced their own versions of the idea, and the 1992 Democratic Party platform included a commitment to introduce enterprise zones. Indeed, to the disappointment of those looking for a comprehensive federal response to the inequities highlighted by the Los Angeles uprisings, Bill Clinton called for “new incentives for the private sector, an investment tax credit,” and “urban enterprise zones.” Democratic support only increased in the late 1980s and early 1990s despite growing signs of the shortcomings of the enterprise zone approach.

Once elected, Clinton directed Vice President Al Gore to develop enterprise proposals for cities. Concerned that the language sounded overly Reaganite, Gore rebranded the Democratic version as “empowerment zones.” In keeping with the New Democrats’ “third way” approach, the program blended targeted tax incentives—including those designed to encourage the hiring of zone residents, relief from property taxes, and accelerated depreciation—with $1 billion in block grants. At the same time, Clinton was keen to reassure voters that empowerment zones did not signal a return to big government: “this is no Great Society,” he intoned. In 1994 nine cities won empowerment zone status—Atlanta, Chicago, New York (which got two zones), Cleveland, Baltimore, Detroit, Philadelphia-Camden, and Los Angeles—and three years later, an additional fifteen urban zones were granted the designation.

In short, the idea of using tax breaks to nudge private investment has been a central instrument of neoliberal governance for decades. As historian Quinn Slobodian notes in his new book, Crack-Up Capitalism (2023), the central innovation it marked in urban planning was “the way it short-circuited local government and handed control straight to developers.”

The evidence regarding the performance of the enterprise and empowerment zone programs is remarkably consistent. It suggests that they were either ineffective in stimulating new economic activity, or, in the rarer cases where new activity can be attributed to zone incentives (as opposed to activity that was likely to have occurred in any case), extraordinarily expensive. In their exhaustive 2002 study of seventy-five enterprise zones in thirteen states, urban planning scholars Alan Peters and Peter Fisher found that the tax incentives had “little or no positive impact” on economic growth. Likewise, in their 2014 book on empowerment zones, Michael Rich and Robert Stoker argued that although “several EZ cities produced improvements in their distressed neighborhoods . . . the gains were modest.” They concluded that “none of the local EZ programs fundamentally transformed distressed urban neighborhoods.”

In the UK, supporters of enterprise zones highlight the Docklands, which went from a derelict port to a thriving financial services hub. In 1988 Howe returned to Dockland’s to laud the transformation. “Ten years ago today,” he proclaimed, “we set out together a future vision of economic revival which accepted as its first base the beneficence of the capitalist system. Ten years later the sight we survey exceeds our wildest dreams. The future we saw then is successfully at work today.”

Yet the government’s own assessment shows that relatively few jobs were created and that each one cost $35,000 to $45,000 in spending and lost revenue. Furthermore, the much-heralded trickle-down effect appears wholly theoretical. The area is still home to some of the most “income deprived households” in the UK. Indeed, Tower Hamlets ranked as the most deprived local authority in London (out of thirty-three such regions) and the 24th most deprived in England as a whole (out of 326) in 2015. As of 2019–20, some 56 percent of children in Tower Hamlets live in income-deprived households—the highest rate in England. By contrast, as of 2023, the average salary of those working in Tower Hamlets is £74,930, while the median household income in 2019 was £30,760—suggesting that financial services workers are largely commuting into the area, and that whatever community wealth is being created isn’t going to the worst-off. The region’s economic transformation has thus exacerbated inequality and delivered little tangible benefit to poor.

A similar story is unfolding in the United States with OZs. Though Congress and the Treasury have failed to mandate reporting requirements, numerous attempts have been made to get a handle on where the money is going, what kinds of projects are being stimulated, and who benefits. Some patterns can be readily discerned. The congressional Joint Committee on Taxation has found that as of 2020, OZ funds held $48 billion in assets, 86 percent of which is invested in real estate, finance, insurance, and holding companies. Moreover, it estimates that OZs will cost the federal government $8.2 billion in foregone tax revenue for fiscal years 2020–24, with the costliest elements coming due in 2028. All told, it could cost as much as $103 billion after ten years.

Given the scale of the program, Brett Theodos and colleagues at the Urban Institute have argued that “Opportunity Zones is the largest ongoing federal community economic development program in the US.” But most of this money has gone to a very small percentage of zones: 5 percent of the zones received 78 percent of overall investment; just 1 percent of the zones received nearly half; and half attracted no investment at all by the end of 2020. The law allows 10 percent of OZ funds to be invested outside of the zones, meaning that high-income areas have enjoyed tax-advantaged investment, and as economists at the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis concluded last November, the kinds of census tracts that have drawn investment have not been the poorest. On the contrary, they tend to be more educated and have higher home values than tracts that have been passed over.

On the questions of who the investors are and what kinds of projects they invest in, the evidence is abundantly clear: they are very wealthy, and they are mostly investing in real estate. Given that 75 percent of capital gains are concentrated in the top 1 percent of households, it is not surprising that that average income of OZ investors in 2019 was over $1 million. These investors, naturally, are looking to maximize returns, which is why the disproportionate flow of OZ investment is going into market-rate rental housing and commercial and industrial real estate. Less than 3 percent is going into operating businesses. As economists Ofer Eldar and Chelsea Garber argued last June, there is a “strong mismatch” between the program’s “stated purpose and its actual terms.”

Much to the vexation of OZ supporters at EIG and elsewhere, the press has leapt on examples of OZ investments that seem to violate the spirit of a law intended to stimulate new investment and “help the poor.” In Portland, Oregon, for example—dubbed Tax Breaklandia by Bloomberg Business Week—the state nominated nearly all of the city’s central business district for OZ benefits, which meant that investors in projects such as a $600 million development of the downtown Portland Ritz-Carlton will avoid paying capital gains tax. Elsewhere, after his eleven-day stint in the Trump White House, Anthony Scaramucci directed his hedge fund, SkyBridge Capital, to invest in one of Richard Branson’s Virgin Hotels in New Orleans’s already gentrifying Warehouse District. This area gained OZ status despite having little trouble attracting capital; the hotel project was already in the works before OZs became law but got to take the tax benefit nevertheless.

Baltimore, Maryland, is just one of many similar examples. The Port Covington neighborhood drew particular attention when it was revealed that Maryland’s Republican governor and part-time real estate developer, Larry Hogan, revised his nominations to include the tract, despite being told by officials that it did not qualify. The community had relatively few people, was not poor, and was surrounded by mostly high-income tracts, but since a sliver of a parking lot within Port Covington fell within a qualified tract, it gained OZ status after assiduous lobbying efforts on behalf of a project bankrolled by Goldman Sachs’s Urban Investment Group and Under Armour founder Kevin Plank. (It was subsequently found that the overlap was actually due to a mapping error, but the tract remained an OZ.) The project, already underway with the aid of state and city tax breaks before designation, aimed to build a hotel, offices, market-rate apartments, and retail aimed at millennials. In the words of urban studies scholar Robert Stoker, Port Covington’s designation as an OZ is “a classic example of a windfall benefit.”

In his recent book, Wessel scoured the land to identify positive cases—those that did seem to correspond to the spirit of the law and reflect the aims set out by OZ evangelists. He did find some, including the SoLa Impact project that has built genuinely affordable housing in Los Angeles; the Chicago Cook Workforce Partnership, which used QOF capital to construct a new building in which the investors are not charging rent above that needed to cover property taxes; and investment in affordable housing and a local newspaper in Brookville, Indiana. But, as Wessel points out, these kinds of projects “draw fewer OZ dollars than the office towers, condos, and luxury apartments. . . . the OZ money going to heavily celebrated, heart-warming projects appears to be a small percentage of total OZ investments.”

In short, enterprise and opportunity zones face six key problems:

1. They reward the wealthy for making investments they would have made anyway.

The aim is to stimulate new investment that would not have occurred without the tax incentives. But the risk—and the reality in the overwhelming proportion of cases—is that tax expenditures go to subsidizing developments that would have happened anyway. As a result, government is wasting potentially vast amounts of money. This pattern is clearly evident for OZs, which led economists Patrick Kennedy and Harrison Wheeler to conclude in April 2021 that OZs “disproportionately benefit a narrow subset of tracts in which economic conditions were already improving prior to implementation of the tax subsidy.”

2. They amount to shuffling the decks.

In many cases investors are simply relocating investments that would have happened anyway so that they occur inside a zone. In other cases, designated zone areas are widened so that projects already in the works receive tax benefits. As in Port Covington, lobbyists have sought to persuade governors or the Treasury to add certain census tracts because of planned investments that fall just outside the zone. In one particularly egregious example, Florida’s then-governor, Rick Scott, amended his nominations for OZs in order to add a tract in which a donor, Wayne Huizenga Jr., had planned to develop a superyacht arena. In these cases there is no net new investment; money is simply moved around.

3. They pay little attention to who exactly is benefitting.

Even if the tax incentives spark new investment, the distributional consequences are ignored; it’s usually the wealthy—not the poor—who are benefitting most, or benefitting at all. The construction of market-rate housing in distressed neighborhoods is more likely to push residents out—or force them to spend even more on rent—than to benefit them. As Kennedy and Wheeler note, “the direct tax incidence of the OZ program is likely to benefit households in the 99th percentile of the national household income distribution.” The conceit that these rewards will be shared with low-income earners is just another holdover of trickle-down economics.

4. They risk making things worse for the poor.

Indeed, OZs may even exacerbate inequality. Besides displacement, new investment can trigger gentrification as expensive coffee shops, microbreweries, and boutique clothing stores replace diners, dive bars, and Dollar Stores. From the point of view of the gentrifier, the neighborhood has improved, but the ordinary resident faces rising cost of living and a diminished sense of community.

5. The benefits—when they exist—may not be justified by the costs.

Even in cases where zone incentives seem to have a made a difference without fueling displacement and gentrification, the costs associated with foregone tax revenue must be weighed against what could have been done with.

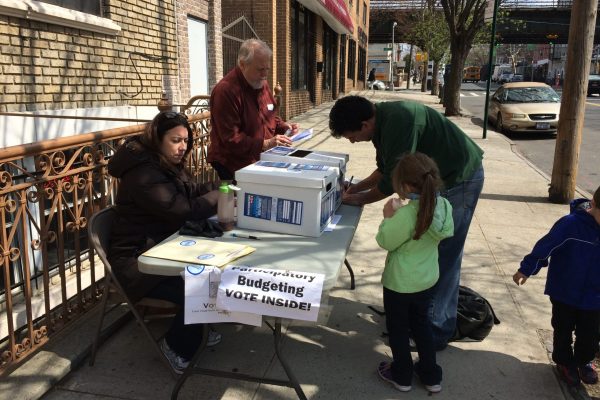

6. They are undemocratic.

With the possible exception of empowerment zones, the zone idea fails to give residents any say as to what kind of investments they want or need. Unlike mechanisms such as participatory budgeting, which empower residents to have a say in the way local government revenue is spent, poor people are excluded from all OZ decision-making processes; the best one can hope for is the good intentions of venture capitalists and state governors. The reality is that most investors are motivated by avoiding tax and securing profitable returns; whether poor people benefit doesn’t factor into their decisions.

Fortunately, there are alternatives.

The first step is to strike at the ideological heart of the matter. In essence, the zone approach is based on the claim that what poor areas need is more capitalism: taxes and regulation are considered fetters on private investment, which is portrayed as the only efficient or valid means for combatting distressed communities. As Butler put it when I interviewed him in 2015, “the capital gains tax argument, which is what Kemp and [Joe] Lieberman and myself were arguing, is the ‘risk-taking’ argument. In order to help small businesses get access to capital, you have to make it worthwhile for venture capitalists to say, ‘I’m prepared to gamble on this and I want my reward from success.’” In reality, unfettered capitalism is to blame; as capital sweeps in and out of neighborhoods, all but the lucky few are left behind. What these communities need is not greater exposure to venture capital but protection from capricious cycles of disinvestment, displacement, and rent-seeking.

Second, rather than focusing on enhancing the exchange value of land—which is of little use to non-property holders and of only marginal use to those who own property to live in rather than as an investment vehicle—urban policy should be directed to enhancing the use value of land. In 2019 Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon proposed legislation to prohibit OZ investments in stadiums, self-storage, and luxury apartments, but even if this were to pass into law—a slim chance in today’s Congress, especially given the pro-OZ groups that have now mobilized to protect their interests—it likely would not stimulate the kinds of investments needed to materially improve deprived neighborhoods, in part because shareholder primacy leads investors to chase short-term profits.

A more substantial vision for reform was proposed last May by Representative Lloyd Doggett and Senator Sherrod Brown, including a Wyden-like provision prohibiting high-end development as well as a requirement that QOFs include community representation on their boards and “provide meaningful opportunities for community input.” But again, the chances that a bill with truly “meaningful” community empowerment would pass is slim, and even if it did, investors would likely judge the resulting program as too saddled with red tape and park their money elsewhere. Moreover, this was precisely the approach taken in empowerment zones, which proved largely unsuccessful. We should look instead to direct state investment in social infrastructure of the sort that legal scholar Richard Schragger urges in his book City Power: Urban Governance in a Global Age (2010)—from affordable housing, schools, and good-paying jobs to medical clinics, playgrounds and sports facilities, libraries, and affordable, high-quality public transit.

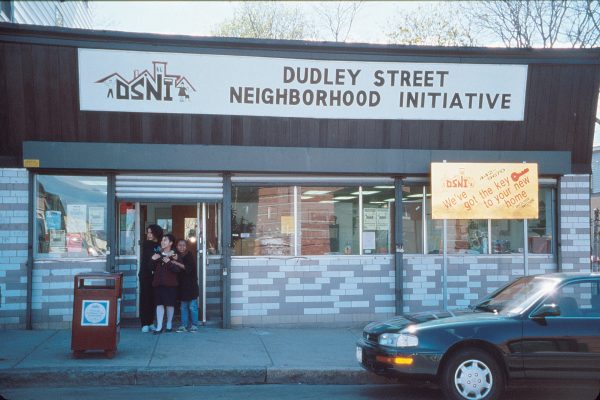

Third, we must think beyond tax-based redistribution, which otherwise leaves capitalism to its own devices. An alternative strategy is to strike at the heart of capital itself to change the institutional foundations of our political economy and create new forms of ownership and production that put wealth and power in the hands of ordinary citizens. As Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill argue in The Case for Community Wealth Building (2019), local communities can be transformed in ways that benefit and empower the working class through networks of collaborative institutions such as worker cooperatives, community land trusts, and public banks. As the examples of Cleveland, Ohio, and the City of Preston in England demonstrate, this strategy can succeed even in places ravaged by deindustrialization and austerity. Indeed, a 2018 study found that, due in part to its community wealth building strategies, Preston was the most-improved city in the UK based on several measures including employment, workers’ pay, inequality, house prices, transport, and the environment. Urban policy and economic development should be directed to supporting the kinds of transformations that enable cities to recirculate capital through the community—rather than upward to investors.

In the end, enterprise and opportunity zones are founded on the discredited premise of trickle-down economics. In this, they reflect a failure to learn the lessons of the past. We should bury this zombie idea once and for all. Only then will we be empowered to build a just future for all communities.

Read a response to this essay by Timothy J. Bartik. Independent and nonprofit, Boston Review relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate here.