At the State University of New York at Stony Brook, the syllabus for an Africana Studies summer course entitled The Politics of Race includes prompts for students in need of term paper guidance. The twelve optional topics are deliberately provocative: “Can a Christian or a democrat be a racist?” “I.Q. tests are a means for blaming the victim.” “Zionism is as much racism as Nazism was racism.” A historian visiting from Israel’s Ben-Gurion University complains that the latter topic, thus the course, thus the professor are examples of anti-Semitism. An uproar ensues.

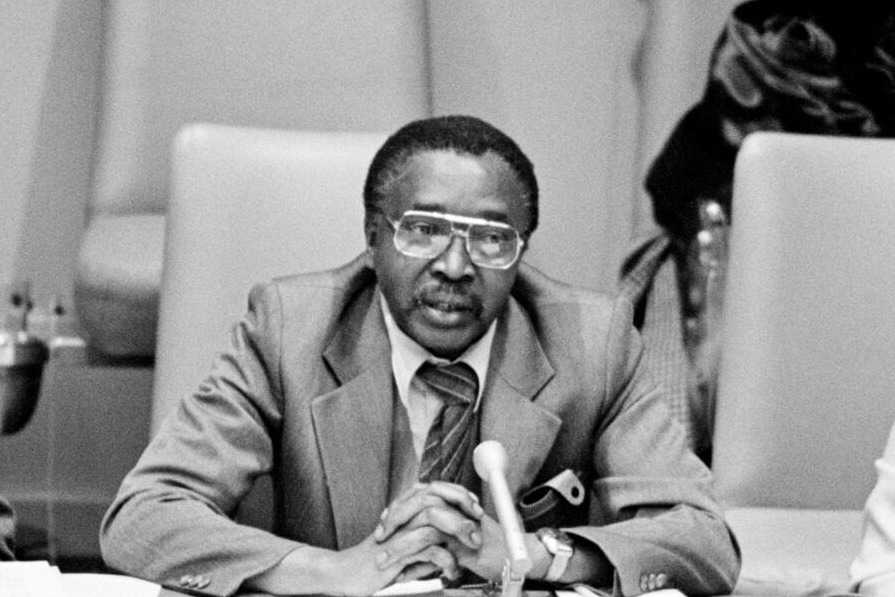

This year is 1983. The professor under scrutiny is Ernest Frederick Dube, the South African anti-apartheid activist, Robben Island survivor, Cornell-trained psychologist, husband, and father. Branded as an anti-Semite, he will be gone from the Stony Brook campus by 1987.

When I began teaching at Stony Brook, my colleagues in Africana Studies told me Dube’s story in different ways. Each time, I understood the lesson: the politics of Israel-Palestine are cordoned-off; they are an arena where you dare not tread. Even when, like Dube, your faculty peers support you, students lead protests against your dismissal, and you are a hero of the South African anti-apartheid movement, you may still end up losing your home and position.

Colleagues outside my department do not know of the Dube affair, but they, like faculty across the United States, are inexorably caught in its gravity. House Resolution 894, eight-hour congressional hearings, push-outs of university presidents, and draconian university policies make it plain: a political firestorm awaits American professors, university administrators, and students who refuse the reductive scripts of Israeli nationalism in public. Before Israel’s latest siege on Gaza and the atrocities of October 7, before the existence of Hamas, before the Canary Mission’s doxxing campaigns, there was Fred Dube.

His story is a spectacular example of how mere complaints can morph into crises when they trigger levers of power. Over the decades, there have been many Fred Dubes, a parade of losses that testifies to the cost of speaking out about Israel’s nationalist violence (which, of course, is endemic to the nation-state and is neither religiously rooted nor exceptional). Cultural theorist Ariella Aisha Azoulay speaks of an “ideological campaign of terror” weaponizing accusations of anti-Semitism against those who refuse to unsee the region’s violence. Decades of reprisal have produced a practice of stilted sentences, empty platitudes, and maddening silence in institutions that would be bastions of critical thought.

The fear and silencing on college campuses today is not arbitrary or new. It is a policy passed down from generation to generation; it is rigorously and virulently inculcated, dangerous both because of whom it harms and what it buries.

In 1983 a student shared the syllabus from Dube’s summer class with a visiting historian from Israel’s Ben-Gurion University. Incensed, the scholar fired off a two-page letter to Stony Brook’s Dean of Social and Behavioral Sciences, the Vice Provost, the Provost, and fourteen members of the faculty, accusing Dube of the “sloganeering that is practiced by the anti-Semite.” Before doing so, the historian never broached his concern with Dube or attended any of Dube’s classes, which he had taught at the university since 1977 without any complaint. The allegations against Dube were launched on the visiting historian’s very last day at the school; his moment of outrage, though, generated enough heat to explode Dube’s career and send shockwaves through the campus.

Shortly after it was sent, the complaint escalated into a national controversy. The Long Island chapter of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) of B’nai B‘rith, which had gotten hold of the letter, mounted a publicity and lobbying campaign insisting that Dube’s course and teaching were anti-Semitic and should not be allowed to continue. In 1975 the same ADL chapter had lodged a complaint about the university’s affirmative action policy and successfully pushed Stony Brook to back away from a commitment to matriculate “women, minorities, and low-income applicants” at the new health sciences center. This time, the ADL’s concerns were not met with immediate acquiescence. A faculty committee investigated the summer course and found that “the bounds of academic freedom had not been crossed”; campus administrators concurred.

The Long Island ADL’s regional director, Rabbi Arthur Seltzer, was not pleased with the conclusion. Days after the findings were announced, he ushered the matter directly to Albany. At the state capital, governor Mario Cuomo responded swiftly, issuing a statement. Dube’s teaching was a “justification for genocide” and “intellectually dishonest,” he declared; the faculty support for him was unfathomable. Once Albany had spoken, Stony Brook president Marburger also published a letter declaring the linkage between Zionism, racism, and Nazism “abhorrent,” and calling for circumspection and sensitivity.

For the communities mobilized against Dube, this was still not enough. The newspaper Jewish Press recommended “a complete investigation of the credentials of every member of the Stony Brook faculty.” The secretary of the Long Island Association of Reform Rabbis called for President Marburger’s resignation. In an op-ed, Yeshiva University vice president Emanuel Rackman lamented that at Stony Brook, “anti-Semitism was made intellectually respectable in the name of academic freedom.” Rackman’s strongest criticism was reserved for Stony Brook’s Jewish faculty, who had largely affirmed Dube’s freedom to teach critically. These colleagues, Rackman averred, were “act[ing] just as did the wealthy Jews of Germany when Hitler rose to power.” Ironically, a syllabus sentence that referenced the Nazis to question the trajectory of Zionism was publicly outrageous; an opinion article that referenced the same to question the morality of Stony Brook’s Jewish faculty was publicly acceptable.

During this time, letters started flooding President Marburger’s office from alumni claiming that they would withhold donations and warn Jewish students to avoid Stony Brook. State lawmakers threatened the university budget. The SUNY Board of Trustees chairman, Donald Blinken, issued a public statement “denouncing the comparison of Zionism and Nazism as a ‘reprehensible distortion of reality.’” In the face of a recognizable storm—donors, politicians, alumni—President Marburger acted. He issued a new statement officially “divorcing” the university from the views in Dr. Dube’s course and began attending public relations meetings with community members at local synagogues. His administration appointed a special Commission on Faculty Rights and Responsibilities to “review courses dealing with race and sex.” Later, the university sponsored a symposium on “Academic Freedom, Academic Responsibility and Society” featuring Rabbi Arthur Seltzer as one of the panelists. Marburger even promised to establish a new Stony Brook Regional Relations Advisory Council, a development that the ADL praised as an opportunity to “provide significant community input” into the university’s academic mission. In the 1983–84 academic year, Dube’s faculty peers offered affirmations of academic freedom, the program of Africana Studies held teach-ins, and there were passionate student marches and glowing interviews with students enrolled in his classes. However, from the first complaint against Dube through his tenure application, appeal, and eventual tenure denial and termination, Blinken and Chancellor Clifton Wharton would receive a steady stream of direct correspondence urging the university to deal with the problem of Fred Dube.

The threats facing Dube were not limited to his professional reputation or his department’s budget. In the same year, the Jewish Defense League, a radical organization that the Southern Poverty Law Center says “preaches a violent form of anti-Arab, Jewish nationalism” and its more militant wing, the Jewish Defense Organization (JDO), came onto the Stony Brook campus, organizing protests and putting up flyers about Dube. In November, Mordecai Levy of the JDO entered the offices of the Africana Studies department demanding that Dube either apologize or resign.

Before leaving campus, the JDO handed out leaflets bearing their symbol, a machine gun inside a star of David, accompanied by the text “Fire Dube or Else.” In the student newspaper, the Statesman, Levy promised that the pressure was only beginning. “We plan to make it as unhealthy as possible to be an anti-Semite. Dube’s phone number and address have been given out. We are going to drive him crazy,” he wrote. Several days later, a member of the JDO entered and attempted to disrupt an Africana Studies class. Then, alongside harassing phone calls and threats, Dube’s home in Uniondale was broken into and vandalized. Throughout this period, Fred Dube continued teaching, speaking, and building his profile; soon he would be up for tenure.

When SUNY Stony Brook Dean Robert Neville vetoed Dube’s tenure in 1985, he did so against the recommendation of the university’s faculty committees. Neville argued that his decision did not reflect acquiescence to the “outsiders who call me at home in the middle of the night to insist I fire him because he says the wrong things about Zionism.” Dube maintained that the administration had caved in to external pressures. Faculty reviewers of Dube’s tenure file noted that he hadn’t published as much as was expected at a research university, even as they recommended tenure. This “lack” of sufficient publications then became the Stony Brook administration’s public justification for his termination. When the campus supported Dube, noting that he was a beloved teacher who brought with him enormous political and cultural resources, the administrators could note that his publications were thin. When Dube appealed his case, the university administrators insisted that his publications were lacking. But to his students (who at one point formed a united front organization and collected over five hundred signatures to send to the Chancellor), Dube was irreplaceable.

If the Dean was still receiving phone harassment about Dube two years after the summer course, what might Dube and his family be facing? During this period his wife, Melta, lost her job and struggled to find another. They abruptly sent their youngest daughter to live with relatives in England. “They needed a scapegoat,” Dube told a crowd of hundreds at a 1985 Stony Brook rally. “I am refusing to be their sacrificial goat!” Still, political pariahdom comes with public and private consequences. The ransacked house, the abrupt move, the charity boxes of food—how do these settle into a family’s story? They can stretch it in unexpected ways: a recurring argument, another bottle of beer, a wrecked car. When the Jewish Defense League claimed responsibility for firebombing the Long Island home of an alleged Nazi war criminal in 1985, Dube and his family had seen enough. They moved out of Uniondale to New York City.

In the 2014 essay “What This Poet’s Body Knows,” Kwame Dawes explores the politics of U.S. racism as a type of “cynical jujitsu,” where the accusation “racist!” becomes the epithet, not the word “n—”. This topsy-turvy weaponization of outrage, for Dawes, is linked to his body. The poet is a “black body exposed and vulnerable” even at the very moment he is said to be a threat, an attacker. The Palestine exception on U.S. campuses depends on a similar “cynical jujitsu”: the suffering of Palestinian bodies, and the harm meted out against those bodies who dare to see it and speak it, is automatically reframed as a threat. The “retort has become the obscenity, the act of violence, the attack.” From the 1980s until today, Fred Dube’s harrowing experience at Stony Brook is unaccounted for.

Twenty years before the Stony Brook summer course, Dube was inside a cell in the infamous Robben Island, caught in the apartheid South African government’s desire to incarcerate, impoverish, and kill Black South Africans’ fight for freedom and equality on their own soil. He spent four years in prison, then left the country as an exile to pursue higher education. Now, in the United States, living for the first time in a country where freedom of speech and academic freedom were valued, at least in name, Dube was “deprived of his job on the basis of the false accusation of anti-Semitism,” an Albany anti-apartheid group argued in 1987. The group, which usually uplifted the cause of freedom fighters in places like Pretoria or Namibia, directed its people to write the SUNY acting chancellor on Dube’s behalf.

This irony of again falling foul of the government, again becoming a political target, did not escape Dube, who remarked to his friends that life as a persona non grata in New York was worse than his situation as a political target in apartheid South Africa. At least in South Africa, he said, everyone understood the reality of life under a repressive government: you and your family didn’t suffer alone. In this peculiar U.S. political milieu, repressive forces used “bureaucracy rather than barbed wire” to bridle free speech, argued Amiri Baraka, then Dube’s colleague. Here there was no cadre with which to traverse this terrain of blacklisting and politicized targeting; his had been made to be an isolated case.

Dube’s political consciousness had been forged outside of the United States, in an entirely different setting. Since the 1960s, he had been part of the African National Congress (ANC), the vanguard political organization that presided over the end of South African apartheid just ten years after the syllabus uproar. Even from his place in exile in the United States, Dube’s scholarship and teaching were part of the struggle: he wanted people to understand that racism blighted both the oppressor and the oppressed.

In the Philosophical Forum, Dube wrote about the multidirectional violence of apartheid’s racism: “The Afrikaner child is in fact the victim, privileged as he may be in other respects, of systematic indoctrination; and the correlative inhibition of critical or independent thinking.” The scholar’s exploration was never solely theoretical. He referenced an unexpected friendship with a prison guard at Robben Island to demonstrate how apartheid psychologically limited white Afrikaners, turned them into cogs in a violent system. Understanding that racism harms both oppressed and oppressor, that these systems have two categories of victims, not just one, was foundational to the reconciliation at the end of South Africa’s apartheid system.

Dube’s challenging and humanizing revolutionary politics were also present in his 1983 SUNY course, The Politics of Race. In one class lecture, Dube discussed a concept he called “reactive racism,” which he defined as “racism that comes from people who are under oppression or were under oppression and use it in self-defense.” He was concerned with how oppressed peoples may come to embrace some of the violent and negative ideologies that they fought against. In his course, he offered two illustrations: the anti-white sentiments of some of his ANC cadre, and the unfolding history of political Zionism.

Both examples were deeply important to Dube. He had watched Israel’s relationship to the South African anti-apartheid struggle shapeshift in his lifetime. The radical core of the ANC’s activists and leaders included many Jewish South Africans, among them some staunch Zionists. Arthur Goldreich, a member of the Jewish Nationalist Movement and veteran of Israel’s war of independence, was also a member of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC. He and Nelson Mandela studied together, drawing military lessons from Zionism, which some ANC members initially viewed as a national liberation movement.

In the 1950s and early ‘60s, Israel occasionally criticized South Africa’s racist policies at the United Nations. Apartheid South Africa was quick to retort that this was rank hypocrisy. “They took Israel away from the Arabs after the Arabs lived there for a thousand years. . . . Israel, like South Africa, is an apartheid state,” insisted South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd. 1948 was both the year of Israel’s founding and the year when Verwoerd’s racist National Party entrenched apartheid as the policy of the South African state. With the occupation of Palestinian territories in 1967, Israel’s relationship to the anticolonial world shifted. The two countries—occupying Israel and apartheid South Africa—began to approach each other diplomatically. By 1976, the South African prime minister John Vorster, a former Nazi sympathizer, was invited for a state visit to Jerusalem. The National Party regime in Pretoria articulated its growing bond with Israel in this way: “Israel and South Africa have one thing above all else in common: they are both situated in a predominantly hostile world inhabited by dark peoples.”

In response to the emerging South Africa–Israel alliance, and amid much controversy, the United Nations passed Resolution 3379 in 1975, which “determined that Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.” In the United States, elected officials like Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan denounced this resolution as an anti-Semitic Soviet ploy, insisting that the African countries in support were pawns of the USSR.

It was from this vantage point that Dube created a syllabus steeping undergraduates in the complex histories of the ANC, South African apartheid, the UN, and the politics of racism. In his 1983 summer course, Dube referenced UN Resolution 3379 and encouraged students to analyze its validity or invalidity. However, conservative forces on U.S. campuses brook no context or complexity where Israel is concerned.

Four decades after the political firestorm, the scars of Fred Dube’s experience are fresh and weeping. Donald Blinken, the SUNY Board of Trustees chairman who publicly condemned Fred Dube, has passed away. His son Antony, as the U.S. Secretary of State, circumvents Congress to rush weapons to Israel to continue a siege on Gaza that has slaughtered over ten thousand children in one hundred days and counting. Mario Cuomo, the governor who denounced Dube’s teaching and reviled UN Resolution 3379 as a lie “second only to the myths of Nazism,” is also gone. But his son, former governor Andrew Cuomo, calls for the National Guard to be deployed against protesters calling for ceasefire in Gaza. The Israeli-American historian who first accused Dube has lost beloved family members to the atrocities of the October 7 Hamas attack. The International Court of Justice recently held public hearings over ANC-led South Africa’s application accusing Israel of genocide in Gaza.

The question posed on Dube’s syllabus—about the relationship between Zionism and racism—remains as relevant as it was then, although in many places, it still cannot be explored without fear of reprisal. The UN resolution labeling Zionism a form of racism was revoked in 1991 in an effort to get Israel to participate in a peace process. In the United States today, college presidents have lost their jobs over accusations of tolerating anti-Semitism; student groups have been disbanded for daring to speak in support of Palestine; student protesters have been blacklisted from future jobs. In November, three Palestinian college students were shot in the streets of Vermont for wearing a keffiyeh, for speaking Arabic.

Forty years later, Zola Dube remembers losing her father to bitterness over the Stony Brook ordeal. Am I afraid, she asks me, to write about Fred Dube? The cycles continue: the impermissibility of critical dialogue about Israel-Palestine is a lesson that we—faculty, administrators, neighbors, citizens—all learn through experience. The time has come again for Dube’s humanizing analysis. What cannot be named cannot be healed. What we cannot speak of, we can never solve.