Until recently, scientific warnings that human activity is causing global warming went largely unheeded. Even less attention was paid to arguments that affluent societies will need to adopt dramatic changes—in consumption, in lifestyle—if they are to bequeath any kind of habitable planet to future generations. On the contrary, environmentalists, green politicians, and their followers were widely ridiculed for being nostalgic, even retrograde. Over the last decade, however, climate science has provided so much evidence of humanly caused global warming—and the resulting floods, fires, and heat waves have become so much more deadly—that the ridicule is now instead aimed at those who had presumed that business would carry on as usual. As for the remaining diehard climate denialists, it is they who are now deemed outside the pale of reason.

Nonetheless, it remains a minority who will readily admit to the role of capitalism and its consumer culture in creating environmental breakdown. It is an even smaller number who dare to suggest that the lifestyle generated through the growth economy is not necessarily the most enjoyable. Climate scientists and many economists now accept the importance of moving away from fossil fuel dependence over time. Some even agree that affluent societies cannot continue in their current ways. But they do so with regret—with a sense that more austere consumption, though necessary, will be to our disadvantage. Even those who are skeptical about the whole project of “green growth,” and who quarrel with the cost–benefit calculations used in support of it, too often go along with the consumerist definition of the “benefits” in question. They don’t question whether consumption actually benefits us, nor whether, if we consumed differently, the beneficiaries might not only be future generations but we ourselves. Most politicians and business leaders seem likewise incapable of thinking of the “good life” other than in terms of consumerist gratification. Obsessed as they are with economic growth and GDP, they do not invite electorates to entertain other ideas of progress and prosperity, and are more than happy for advertisers to retain their monopoly over how pleasure is imagined. Mainstream politics thus remains dominated by narrow disputes over the means to a commonly agreed set of ends (economic growth, technological development, increased standards of living as defined by current consumer culture).

Nor is this much challenged even by those further to the left, where the tendency to disconnect from issues of material culture has discouraged most from trying to imagine a radically different vision of ethical consumption. Thinkers on the left will agree that capitalist production is a historically specific mode of production, and condemn its human and environmental exploitation. Yet the consumer culture it has bequeathed is often accepted as if it were a natural legacy to be preserved as far as possible—with socialist economics directed at providing its affluence for everyone in abundance. Critics of the current economic order have usually been more bothered about the inequalities of access and distribution it creates than about the ways it confines us to market-driven ways of living. Labor militancy and trade union activity in the West has likewise been largely confined to protection of income and employees’ rights within the existing structures of globalized capital, and done little to challenge, let alone transform, the “work and spend” dynamic of affluent cultures. Even among the less pragmatic thinkers on the left—the so-called “tech utopians” and “luxury communists”—something of the consumerist mindset persists. The future that is promised will be more idle (thanks to robots and drones doing most things for us), but it remains conventional in tying much of its pleasure to the continuation of automobile culture and the expanded availability and use of machines and hi-tech gadgetry.

This forum is featured in The Politics of Pleasure.

The presumption, however, that more sustainable consumption will always involve sacrifice rather than improve well-being needs challenging. Our so-called “good life” is, after all, a major cause of stress and ill health. It is noisy, polluting, and wasteful. Its work routines and commercial priorities have forced people to plan their whole lives around job-seeking and career. Many are condemned to unfulfilling and precarious work lives in the gig economy. Even those with more secure employment will frequently begin their days in traffic jams or suffering other forms of commuter discomfort, and then spend much of the rest of them glued to a screen engaged in mind-numbing tasks. A good part of their productive activity is designed to lock time into the creation of a material culture of fast fashion, continuous home improvement, urban sprawl, speedier production, and built-in obsolescence.

Our consumption economy’s markets profit hugely from selling back to us the goods and services we have too little time or space to provide for ourselves. Consider the role of the fast food, leisure, and therapy industries, or the gyms where people pay to walk on a treadmill because walking anywhere else is impossible or unpleasant. These markets’ merchandising strategies promote competitive forms of consumption, especially among the young, often relying on devious means such as body-shaming, thus worsening anxiety and depression. These markets also now subject all online shoppers to the insidious advertising strategies of what has been called “surveillance capitalism,” while at the same time off-loading onto the consumer much of the servicing and bureaucracy that businesses used to perform themselves.

Greens, then, may get dismissed as regressive killjoys, and have played into this characterization by presenting reduced consumption as only necessary rather than personally rewarding, even pleasurable. But the reality is that today’s work-dominated, time-scarce, junk-ridden “affluence” is itself the killjoy, and often puritanical and sensually offensive. Moreover, it does not arise from any innate desire of people constantly to work and consume more. If it did, the billions spent on advertising, and especially on grooming children for a life of consumption, would hardly be necessary.

It may be objected, especially in these times of intense economic hardship for so many, that in advocating the pleasures of escaping the consumerist lifestyle, I overlook how partial the access to its forms of affluence has actually been. What sense, it will be asked, can my argument have for those increasing numbers who currently wonder how they will provide even such basics as food, clothing, and heat. Critics may rightly note that even in better times, few have ever really been in a position to enjoy much of the comfort or luxury associated with affluence. I am sensitive to these objections. But they overlook the extent to which the consumerist lifestyle functions in affluent societies as a regime in which we are all caught up, whatever our income. Viewed in this light, people who are on the breadline, or only just managing, have not escaped the constraints of its work ethic or on what they can do and how. All are subject to them. Even among the adequately employed, most have too little time and not enough income to consume more sustainably even if they want to. Hence their reliance on buying ready meals or processed food, quick air flights for compressed family vacations, cheap goods from Amazon, and so forth.

Consumer society is, in this sense, itself a vehicle of inequality and the provider of a distinctive form and aesthetic of material culture to which we must all, in one way or another, conform. Although often acclaimed as the guarantor of universal freedom and self-expression, it might be better viewed at this stage in its evolution as a means of extending the global reach and command of corporate power at the expense of the health and well-being of both the planet and the majority of Earth’s inhabitants. In exchange for this misery, it offers the “compensation” of goods and services which, though intensely profitable for corporations, fall far short of making up for what has been lost through overwork. Considered in this light, we should not think of the changes forced by the climate crisis as a disaster, but rather as an opportunity to embrace a fairer, more enticing way of living.

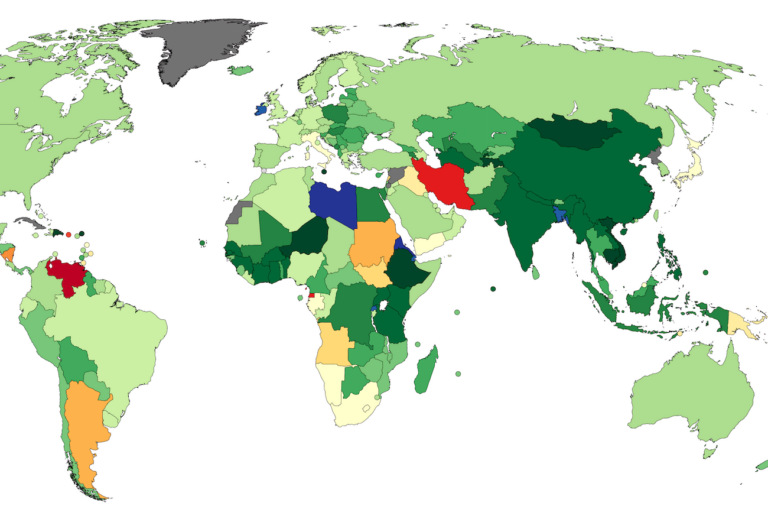

I would respond along similar lines to the equally relevant objection that my argument overlooks the importance of a continuing growth economy in meeting the needs of those in so-called under-developed or developing nations. I accept that economic growth will be needed in the short term to ensure the provision of basic needs in the poorest nations. I also agree with economist Kate Raworth that growth may temporarily result from measures undertaken to secure a “regenerative and distributive” economy—for example, to establish an infrastructure for renewable energy. But the overall aim must be to wrest control of global wealth and material resources from the grip—and accompanying ecological dereliction—of a relatively small corporate elite. Between 1990 and 2015, the world’s richest 10 percent produced over half of all carbon emissions while the poorest 50 percent produced less than a tenth. It is also the poorer nations who are doing the least to create climate breakdown yet who are suffering most severely from its social and environmental impacts.

It is therefore absurd that nations whose citizens’ consumption grossly exceeds the planet’s carrying capacity should continue to be held out as aspirational models for the rest of the world. Capitalist-driven consumer culture should no longer be allowed to exercise its monopoly over conceptions of well-being and how to secure it. Indeed, societies with traditions of less industrialized but more sustainable methods of production and modes of consuming must surely begin to count as more progressive. This has long been recognized by many indigenous activists and critics of the current neoliberal thinking on development. In the words, for example, of Nemonte Nenquimo, cofounder of the indigenous nonprofit organization Ceibo Alliance, and first female president of the Waorani organization in the Ecuadorian Amazon:

You forced your civilisation upon us, and now look where we are: global pandemic, climate crisis, species extinction and, driving it all, widespread spiritual poverty. In all these years of taking, taking, taking from our lands, you have not had the courage, or the curiosity, or the respect to get to know us. To understand how we see, and think, and feel, and what we know about life on this Earth.

In line with this, in my book Post-Growth Living (2020) I emphasize the need to revise and revalue concepts of prosperity and development in order to bring them more in line with the more sustainable ways of living and working that have so often been swept aside by capitalist “progress.” This would not endorse a “back to nature” ethic through which modern “excesses” could be corrected by return to a “simple” way of life. But it would resist the presentism that refuses to look to the past for resources that could help us form a more viable, enjoyable future.

Concerned consumers in more affluent societies must lead the way in this rethinking and thus act as an essential initial leverage for a global green renaissance. The Debt for Climate campaign rightly proposes a global revolt against debt and austerity in which poor world governments refuse to honor their debts and activists in the rich world support them by calling for debt cancellation as well as reparations for the devastating loss and damage caused by our greenhouse gas emissions. As George Monbiot has put it in a recent article: “By reviving the question of who owes what to whom, huge constituencies, labour and green, north and south, can develop a common platform. Climate campaigns are indivisible from global justice.”

We need to be more assertively utopian in promoting sustainable consumption in richer nations. I don’t mean only that our blueprints must be more openly utopian in the futures they plan for, but that we must also actively encourage desires and feelings to match. The new consumption is not a matter of simplifying needs and wants. Rather, we want a world that provides more of what we currently lack, and which opens the way to previously unconceived experiences. In what follows I explore this idea by charting (in a necessarily incomplete way) some of the losses and gains that might follow were we to embrace a new vision of consumption which I call “alternative hedonism.”

Work

Were we to spend less time working—committing, say, to a three- or four-day workweek—the workaholics might lose some of the gratifications of a 24/7 job-centered lifestyle. But many people would be spared the hassle and expense of daily commuting and the long hours spent on it. They would avoid much of the stress and stress-related illnesses incurred through overwork. The large numbers now employed in financial and administrative services, described by anthropologist David Graeber as often spending “their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed,” would be saved from the futility of their “bullshit jobs.” The less skilled or formally qualified workers of the precariat, who are both exposed to the instability of the gig economy and deprived of occupational identity or career trajectory, would likewise escape from the insecurity and demeaning forms of discipline associated with dead-end work.

In a working culture no longer dominated by profit-driven ideas of efficiency, we could reintroduce traditional artisanal modes of production which fell out of favor because they are slower, while employing the smartest, greenest technologies in those industries where such methods of production would not be suitable (energy and medicine, for example). Methods of production that featured closed-loop cycles of resource use, and which gave priority to upcycling over recycling, would put an end to built-in obsolescence and radically reduce waste.

Artisanal “slow working” could make space in some areas of production for those currently excluded by age or disability, and help to enhance job fulfilment. Let us add to this the greater pleasure that people would experience knowing that their work no longer contributed to environmental breakdown, nor threatened the very survival of their children and grandchildren. Such a shift would also put an end to many of the more dispiriting jobs—those, for example, devoted purely to brand enhancement and the merchandising activities that go with it.

The reduction in work would necessarily need to proceed in tandem with the introduction of some form of citizens’ or universal basic income. This would allow people to make good use of their increase in free time, and make them better able to enjoy the novel forms of cooperative consumption and conviviality it could promote. It would also lessen inequalities and help to promote a less gendered, racialized, and class-based division of labor. Society would necessarily shift from a work-centered understanding of identity, purpose, and self-fulfillment to one that revolved around more self-chosen ways of spending time and energy. In turn, the work ethic that so stigmatizes the unemployed would loosen its grip, and more encouragement could be given to self-provisioning, as well as to craft-based and cultural activities, games, hobbies, and other intrinsically valued ways of spending time.

Educational priorities would need to be revised accordingly, with a shift from a too purely vocational focus—education as preparation for work and career—to one that made space for instruction that enhanced the enjoyment of free time. This would extend from elementary school through to higher education and beyond. As much time would be given in schools to music, dance, drama, painting, and literature as to the scientific and technical subjects. The humanities would in the process be restored from their rather marginal status, as appreciation grew for how they support non-instrumental values and provide critical resources unavailable through other subject areas. When well taught, the humanities challenge comfortable convictions, thus advancing a more historical, intersubjective, critically honed sense of one’s own identity and place in society.

Travel

Were we to curb dependency on cars and airplanes, we would lose the thrills and convenience of very fast transport. To many Americans, this will seem likely to reduce their pleasure and comfort as well as being financially impossible. Nor, perhaps, will many pay much attention to the now all too familiar advice that we should restrict our use of planes and automobiles so as to offset the destabilizing global impacts of fossil fuel reliance.

In response, however, to the objection that other modes of travel are too expensive to be realistic alternatives, it is worth noting that they would become less expensive were we to use them more: were demand for trains and boats to increase, for example, the costs of such journeys would decrease. Already in Europe, many longer journeys by train cost little more than scheduled flights, save around 90 percent of carbon emissions, and can in some cases take scarcely any more time than flying when journey to airports and preflight waiting times are added on.

But there are advantages beyond the financial, as well. Train and boat travel can provide a richer and more engaged experience of the regions through which one is traveling. Far-flung vacations have become very popular, but they do not always live up to their promise of providing exceptional experiences and can leave travelers exhausted. Vacations taken closer to home—and without the high stakes of needing to generate memories to last a lifetime—may provide unexpected forms of enchantment and serve just as well as escapes from mundanity.

In addition to its carbon emissions, automobile transport has a massive impact on air pollution. Some 300 million children now live in areas where toxic fumes are 6 times above international guidelines, and almost all the global adult population is now affected to some degree. Hybrid and fully electric vehicles will reduce pollution, but large amounts of plastic are still involved in their construction, the electricity they use must be generated, and their batteries need to be sustainably produced and safely discarded. Nor will they necessarily do much to spare us the accidents that are responsible for so much death and maiming (nearly 39,000 lost their lives in traffic accidents in the United States in 2020). Electric machines will also do nothing to lessen congestion or the automobile’s colonization of urban space. Instead, electric vehicles look set to protract the dangers and spatial monopoly of car culture, rather than moving us beyond its mindset.

Road transport is also a significant cause of wildlife and ecosystem destruction at a time when we have been warned that everything now needs to be done to improve conservation. Screened as its users are from the external impact of speed, they are insensitive to its environmental devastation, and cut off from many of the aesthetic pleasures of slower and less insulated modes of traveling. They are confined to what Alexander Wilson, in his 1991 study The Culture of Nature about the making of the North American landscape, called the “motorist’s aesthetic”: a purely visual experience comparable in its two-dimensionality to the view that is had in aerial photography. Scenic routes, Wilson suggests, have instructed generations of drivers in a flattened idea of nature’s “beauty” by “removing whatever bits of it were deemed unsightly, and by restricting all activities incompatible with the parkway aesthetic.” It is a too purely visual aesthetic that has been further reinforced through modern media, since so many now experience “nature” primarily as something seen on TV or screens.

Automobile culture also deprives us of the positive enjoyments of ambling and gossiping and passing the day in urban space. As the Living Streets campaigners have pointed out, urban space used to be mainly devoted to socializing, public meetings, entertainment, demonstrations, and social change. Today much of it is given over to car traffic, cutting swathes through communities. Children have been deprived of safe urban places in which to play, adults are discouraged from idling in the street. Doing so has acquired the negative connotation of “loitering,” which many jurisdictions have even criminalized. Many of what pass for “public” spaces are, in fact, often privately owned and policed—shopping malls and outlets, for instance—and though they at least offer protection from traffic, the more “disreputable” (non-shopping) elements are under continual surveillance and regularly moved on. Nor is seating much in evidence lest non-shoppers take advantage.

Were we to reverse these trends—as some cities are now belatedly beginning to do—then we could readily provide for safe transit for pedestrians and cyclists. This would enable far more people to enjoy sights, scents, sounds, and pleasures—not to mention health benefits—of physical activity. Walking and biking can offer a balm of solitude and silence denied to those who travel in noisier, speedier ways. Freed from traffic dangers, children could come out to play again, and walk or cycle to school. Such provision could take quite baroque forms: multi-lane tracks with handsome colonnades and covered routes for protection from the weather, cycle rickshaws and electric bikes for the too young and less able, showers and changing rooms and cafes at regular intervals on cycle tracks. Utopian as they may currently seem, the costs of such schemes would be small relative to that of continued expansion of autoroutes—especially if one factors in the medical costs likely to be saved through better public health and fewer accidents.

Shopping

If we were to shift to a less acquisitive consumer culture—shopping less and committing to more self-provisioning, mending, and making do—we would miss out on the use of consumption for self-display and status signaling. There would be less stuff in our lives; we would have to forego the enticements of following fashion; we would lose the convenience of Walmart and Amazon.

Conspicuous or invidious consumption (the buying of goods to gain the attention or envy of others) has certainly proved compelling, and expanded the market in many goods, especially in clothing, household furnishings, and electronic equipment. It has thus served the growth economy extremely well. But its gratifications for consumers are complicated by what has come to be known as “hedonic adaptation” and the “hedonic treadmill.” Research suggests that the pleasures of acquisition are not enhanced beyond a certain point, whatever the material gains, while the competitive desire for status goods is like a treadmill: since all are continuously vying to keep up with each other’s acquisitions, no one is finally satisfied.

Similarly, fashion seems to offer ever-changing opportunities to express individuality, but what it actually generates are waves of conformity to whatever is promoted on the market. A promise of self-realization is held out, but only on the condition that you submit to the dictate of a collectivity you have neither willed nor authored. The fashion industry strives to make essentially homogeneous forms of consumption seem constantly innovative and therefore desirable, but does little to promote genuine difference and eccentricity. The result, moreover, is environmentally disastrous. The average American consumer nearly doubled the amount of apparel bought annually between 1991 and 2006. Worldwide over 100 billion items of clothing are produced annually, with brands shoveling excess production into incinerators. A similar logic of fashionable design has developed in IT markets, whose discarded items are now contributing to the fastest growing forms of waste, much of it highly toxic, across the Western world.

To reduce dependence on these sources of gratification would, then, greatly cut down on waste. It would spare us the intrusive and often unsightly sprawl of the hypermarkets and fulfilment centers, and lessen the clutter in homes. In compensation, communal ways of meeting needs might emerge and offer alternative forms of enjoyment. Local cooperatives and social enterprises could expand. So, too, could all those modes of acquisition and consumption that bypass the market or allow people to satisfy their requirements for goods and services without purchasing new commodities from commercial suppliers. These include sharing schemes, flea markets, charity and secondhand shops, and all the resources for the recycling of articles—for which there are now a growing number of websites. Apart from the pleasures of person-to-person reciprocity, such exchanges and bartering activities save money and allow people to make use of specific talents and eccentric interests for which they may otherwise have little outlet. The provision of hubs for the hiring, borrowing, and sharing of vehicles, tools, and educational and financial services—not to mention arts centers, supper clubs, and the like—would transform main streets and city centers, and encourage new forms of citizenship (and the pleasures that go with that). It could also lessen isolation for the elderly and lonely by opening up spaces and opportunities for more street conviviality. Allotments and gardens would likely multiply, with more people enjoying the pleasures of growing and eating their own food.

Skeptics will doubt that these more sustainable forms of pleasure can substitute for those of consumerist lifestyles, or win sufficient support to exercise political leverage over the current economic order. It is true that the absence to date of any serious consumer revolt in affluent societies indicates that most at least tolerate, if not actively support, the consumerist way of living. Moreover, although corporate power is extensive and exercises a massive influence on the production and marketing of goods and services, it would be a mistake to present the environmental troubles of our times as entirely accountable to the providing industries and their merchandising manipulations. The appetites of customers in rich nations, and the priority given to their convenience, play a major role, too, and any advocacy of degrowth and a more peaceful, sharing economic order will need to recognize that—particularly if we are to reduce our fossil fuel dependency. To treat “us,” the general public in affluent societies, as victims of “their” entrepreneurial activities is to offer too comforting an escape. The numbers who express concern over the environmental horrors perpetrated by corporate power and government hardly seem matched at present by changes in individual consumer behavior—or indeed in voting patterns.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has run its course, however, signs have emerged that this hitherto broadly shared agreement on the lifestyle we want to preserve may be beginning to fracture. The postconsumerist arguments of previously disregarded groups (such as the Degrowth network and the Next System Project) are finding more traction in the mainstream. So, too, are those of green parties and NGOs campaigning not only for a recommitment to ideas of the commons, and a more participatory economic order, but also for the necessary preceding step of revising how we connect well-being with consumption.

The war in Ukraine has also opened more eyes to the dangers of a world order dominated by the producers of fossil fuels, too accommodating of the nationalism of kleptocrats, and relatively indifferent toward environmental breakdown. Such pressures might mean that the downsides of our fast-paced, acquisitive lifestyle, voiced only by a minority at present, come over time to receive more mainstream support.

That people hanker after something else, and would enjoy it more, has also long had the backing of research studies showing that more wealth does not necessarily make you happier, and that the pursuit of ever more consumption is inherently self-defeating. It is true that such research needs to be treated with caution. Among the complicating factors, the degree of satisfaction people self-report often has little to do with how they are actually faring. Nor does a lack of correlation between higher income and self-reported satisfaction mean that more consumption has not improved a person’s well-being. There are likely many reasons for this disjunct. The standards people use to assess their satisfaction may become more stringent as their wealth increases. Education made available by wealth can improve an individual’s sense of freedom and personal potential precisely by generating discontent with her existing life situation.

These issues raise questions as to what should count in the estimation of the “good life.” Is it the intensity of its more isolated moments of pleasure, or overall level of contentment? Is it the avoidance of pain and difficulty, or successfully overcoming those? And who is best placed to decide on whether personal well-being has increased? Is this entirely a matter of subjective self-reporting, or open to more objective appraisal? Those defending a more objective assessment will point out, first, that people are not always the best judges of their own well-being and, second, that much immediate pleasure can be had from behaviors that are self-destructive or environmentally vandalizing. Relatedly, it has been claimed that a “happiness” conceived or measured in terms of subjective feeling discourages the development of the sense of citizenship and intergenerational solidarity essential to social and environmental well-being.

There is, then, a tension in discussions of hedonism and the good life between privileging a subjective sense of pleasure and reaching for a more objective understanding. Where the former risks overlooking the critical long-term links between the “good life” and the “good society,” the latter runs the risk of being patronizing by suggesting that “experts” understand our own happiness better than we do. Yet the more subjective approach need not exclude the civically oriented forms of pleasure that come with consuming in ways that are responsible to others and to the environment. After all, the pleasure of many activities—riding a bike, for example—consists both in the more immediately personal sensual enjoyments and in the pleasure of not contributing to the vices of car culture, including pollution and urban fragmentation.

In the end, no legitimate claim about someone’s well-being or degree of life satisfaction is possible without some endorsement from the individual in question. It is, however, one thing to accept the complexity of gauging claims about quality of life and personal satisfaction. It is another to deny the evidence of the self-defeating nature of ever-expanding consumption. My alternative hedonism cannot—and does not aspire to—resolve the philosophical issues in this area. Instead, I seek to make clearer the yearnings for alternative ways of living that are implied by emergent disaffection with affluent culture, and point to what they instruct us about pleasure and well-being. My main interest is thus, to invoke a concept of cultural critic Raymond Williams, in a “structure of feeling”—that is, a popular, though still nascent, intuition in the back of people’s minds that something about our conventional life has gone wrong and must change. For me, this “structure of feeling” points toward a postconsumerist vision of the “good life.” My alternative hedonism aims to avoid moralizing about what people ought to need or want—even if a certain amount of that is unavoidable—while still troubling the forms of consumption that have been taken for granted. I hope, so doing, to draw attention to former pleasures gone missing, and to issue a compelling summons to another way of living.

As the planet heats, we need a political response appealing to, and supported by, this “structure of feeling.” It must challenge the stranglehold of the work ethic on the Western way of life, and seek to replace it with a socioeconomic order in which work and income are more fairly distributed, coparenting and part-time work become the norm, and everyone has the means and time for sustainable forms of activity and life-enhancement. Doing so could transform urban and rural living, especially for children, and provide more tranquil space for reflection, offering opportunities for sensual experience denied by harried travel and work routines. It would also help to lay the groundwork for a more egalitarian and peaceful world order.

There are some conveniences and pleasures of affluent living that would have to be sacrificed in a low-carbon economy: creature comforts of various kinds; some of the thrills of fast-paced living; the ease with which we have recently gratified the passion for foreign travel. Shifting to a postconsumerist way of living is also a daunting prospect in view of the integrated structure of modern existence and the subordination of national economies to the globalized system. Yet it is also unrealistic to suppose that we can continue with the current rates of expansion of production, work, and consumption over coming decades, let alone into the next century and beyond. Greener technologies will help to counter global warming. But the implementation of alternatives to the growth economy must become central to planning and policy-making, rather than ignored or dismissed as unworkable fantasy.

My argument for alternative hedonism is frequently rejected as unrealistic. I counter that it is, instead, quite seriously implausible that the future can be “business as usual.” There is an urgent need for a politics of prosperity that dissociates pleasure and fulfilment from resource-intensive consumption. And in doing so, it is important to avoid fanciful assumptions about what would constitute globally sustainable forms of industry and lifestyle. Such a vision must be what frames our discussions of how work, politics, and economics will look in a socially just and viable future.