At its seventy-third annual meeting in Berlin last month, the World Medical Association adopted a statement decrying the harmful effects of racism in medicine. “Racism is rooted in the false idea that human beings can be ranked as superior or inferior based on inherited physical traits,” the statement opens. “This harmful social construct has no basis in biological reality.”

Though race is a social construct, this does not mean that racism cannot produce biological effects. As the statement goes on to explain—and this week’s reading list makes clear—when racism intersects with medicine and health, the results can be deadly.

Consider a biological function as basic as breathing. Black Americans’ higher rates of asthma and other pre-existing conditions have made them more vulnerable to respiratory illnesses such as COVID-19, as evidenced by their disproportionate death and hospitalization. But these rates have social origins; they are the result of structural racism. “Air pollution, stress, occupational hazards, and health care services are distributed, unequally, across the intertwined divides of class and race,” writes pulmonologist Adam Gaffney. “The hierarchies that structure our society distribute not just wealth but breath.”

Racism also manifests in medicine in less obvious but equally pernicious ways—even in seemingly neutral technologies such as pulse oximeters, for example (devices which attach to the finger and measure a person’s blood oxygen levels). As anthropologist of medicine Amy Moran-Thomas shows in an influential essay that has sparked a nationwide reckoning and FDA investigation regarding pulse oximeters over the last two years, a growing body of evidence suggests that these devices work less accurately for patients with darker skin, with potentially dangerous consequences. The discrepancy likely arises in part due to limited diversity among patients enrolled in health care trials, in part due to flaws in design or calibration, and in part due to the medical profession’s failure to follow up on warning signs in the medical literature. Moran-Thomas concludes the devices are a “disturbing materialization of how white supremacy has been built into our systems and infrastructures of perception.”

The essays in this week’s reading list explore these and other ramifications of racism in medicine and health care, as well as possible solutions. Physicians and historians examine the American Medical Association’s elitist conception of what makes a “good doctor”; two medical doctors offer a vision for medical restitution for communities that receive unequal care; and biologist and gender studies scholar Anne Fausto-Sterling calls for an updated medical school curriculum that reflects what we know about how racism and medicine intersect. Elsewhere, an infectious disease researcher discusses the growing role mass incarceration plays in the devastating global toll of tuberculosis, which receives little media attention in the Global North; a historian-psychiatrist considers the fraught place of psychiatry in prisons; and two physicians imagine how health care could be radically reimagined to genuinely promote the well-being of all.

As more and more doctors awaken to the political determinants of health, the U.S. medical profession needs a deeper vision for the ethical meanings of care.

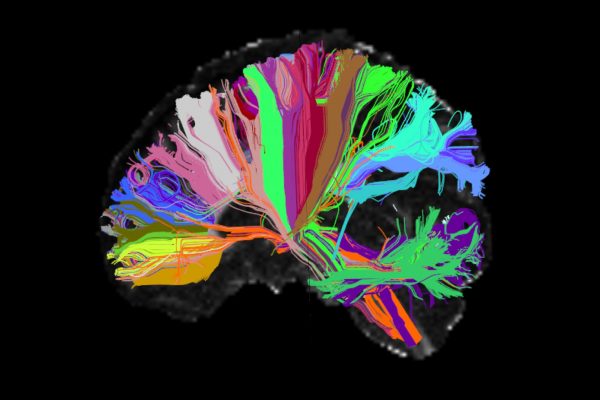

Decades of biological research haven't improved diagnosis or treatment. We should look to society, not to the brain.

Until COVID-19, tuberculosis killed more people each year than any other infectious disease. Its rising toll is increasingly fueled by mass incarceration.

Black people get sicker because of stereotypes taught in medical schools.

American medicine has long functioned as an elitist institution, putting professional prestige over the well-being of patients and physicians alike.

Colorblind solutions have failed to achieve racial equity in health care. We need both federal reparations and real institutional accountability.

Physicians have been fighting for health justice for decades. To succeed, we need practical models for collectively remaking our systems of care.