Americans celebrate Labor Day on the first Monday of September, but for much of the world, the cause of organized labor is celebrated on May 1, International Workers’ Day. The discrepancy is ironic because the history of May Day is closely bound up with the U.S. labor movement’s efforts to secure the eight-hour day.

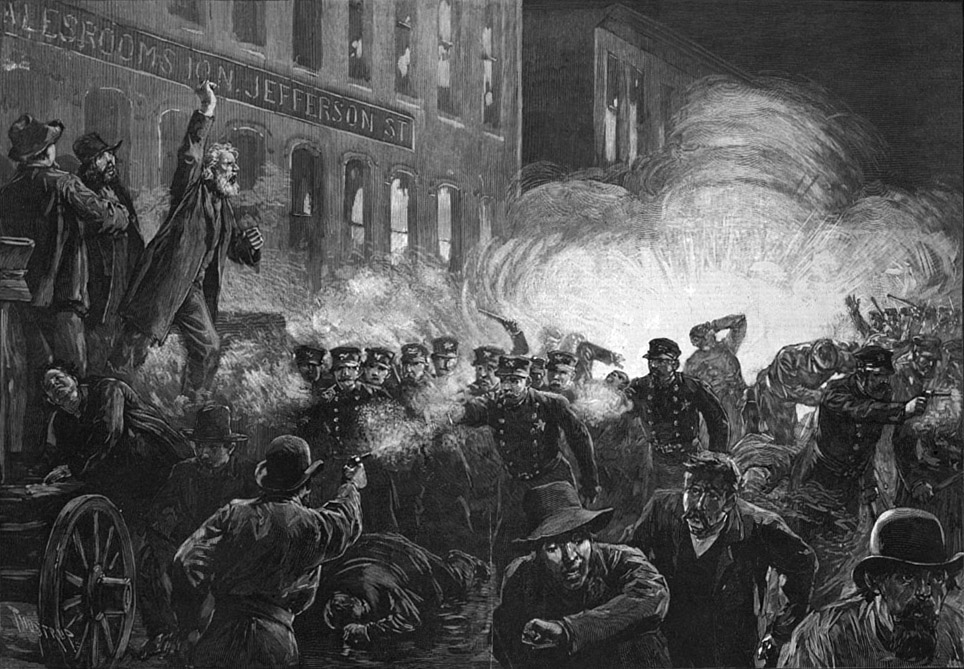

Although the first official May Day took place in 1890 following a call by the Second International for, in the words of historian Eric Hobsbawm, “a simultaneous international workers’ demonstration in favor of a law to limit the working day to eight hours,” it is often associated with the Haymarket affair, a demonstration for shorter hours that occurred in Chicago on May 4, 1886. The peaceful protest turned violent when someone threw a bomb into the ranks of the police officers who were there to disperse the crowd, leading to a deadly exchange of gunfire. Eight anarchists—the “Haymarket Martyrs”—were charged with conspiracy, although only two had been at the rally and none was suspected of throwing the bomb; seven were sentenced to death, of whom four were ultimately executed.

It’s no surprise that International Workers’ Day arose from protests against long hours of work. As economist Mike Konczal explains in a contribution to BR’s special project “Rethinking Political Economy,” shorter hours were one of the primary demands of organizing workers during the growth of industrial capitalism. Forming trade unions and other associations to further their cause, these workers argued that freedom from overwork was essential for physical health and intellectual development, and the cornerstone of a thriving economy and democratic culture. “Shorter working hours contribute to freedom by creating the time and cultural space necessary for civil society to thrive,” Konczal concludes. “In our own era, where we feel that we have no control over our working hours, this is a vision of freedom worth recapturing.”

This vision of freedom as independence from the dictates of the market is shared by many workers today, including those whose work is criminalized, such as sex workers and undocumented immigrants. According to feminist studies scholar Heather Berg, the criminalization of sex work by the state threatens the interests of all workers insofar as it relies on forms of enclosure and surveillance intended to force people into waged work and the loss of autonomy it entails. “Fights to decriminalize sex work name the connections between sex workers and other contingent workers, gig and other informal workers as well as those whose immigration status places their labor in liminal legal territory,” Berg writes. “Sex workers’ struggle against enclosure is resistance to proletarianization itself—to being made a waged worker.”

This week’s reading list features several other contributions to the “Rethinking Political Economy” series, including Black studies scholar Charisse Burden-Stelly and political theorist Jodi Dean on how Black communist women remade class struggle; labor scholar Brishen Rogers on workplace technology as a tool of class warfare; economist Brian Callaci on how antitrust law has failed workers; sociologist Karen Levy on workplace surveillance; political scientist Adam Przeworski on reform versus revolution; and more.

Sex workers are labor's vanguard. The left ignores them at its peril.

Leaders of the left abandoned the language of transformation in the 1980s—at a cost. Can it be regained?

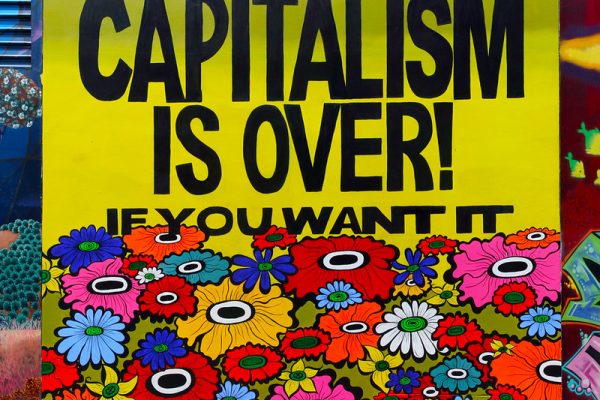

Rumors of the imminent death of capitalism have often been greatly exaggerated. But that doesn’t mean we must give up on making things better.

Forum

Unions are being strangled by laws that block workers from organizing, striking, and acting in solidarity. Becoming a rights-based movement is the only way to save labor.

Intrinsic to what we hate about work is that we can’t imagine life outside of it.

Working people are forever kept on the brink of going broke. More than higher wages and better job security, a just economy requires giving them the power to choose and create their own futures.

And what today’s organizers can learn from them.

Both regulators and employers have embraced new technologies for on-the-job monitoring, turning a blind eye to unjust working conditions.

How a new class of “salts”—radicals who take jobs to help unionization—is boosting the organizing efforts of long-term workers.

The late author of Nickel and Dimed played a major role in women’s liberation and U.S. socialism.

Workers will benefit from technology when they control how it’s used.