In our writing on Haiti over the years and especially since the catastrophic earthquake of January 12, 2010, we have sought to dig deeper than the newspaper headlines and NGO press releases. We have tried to take the long view and contextualize the country’s complex politics in terms of its history, its relations with the United States and other countries, and ideas of race, class, and economics. Our coverage of Haiti includes pieces by Fiction Editor Junot Díaz and longtime contributors Sidney W. Mintz and Colin Dayan.

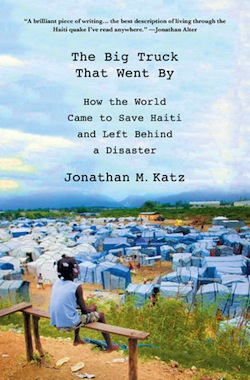

So it was with great anticipation that we received a copy of Jonathan M. Katz’s new book, The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster. Katz was the AP correspondent in Port-au-Prince for more than three years and the book springs from his experiences covering the quake and its aftermath. According to Dayan, Katz’s book is the best thing written about the tragedy. “The great effect of the book is its reticence—that the details are allowed to build up and speak for themselves,” Dayan said. “And they build up into a portrait that’s quite scathing and really powerful.”

We invited Dayan and Katz to discuss his book and to share their thoughts about Haiti. Their conversation took place by phone.

• • •

Colin Dayan: I’d like to begin by going back before the earthquake and asking you a bit about the orchestration of the coup against Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004. I was aware at the time that Secretary of State Colin Powell was sending Terry Stewart, who used to be the director of the Arizona Department of Corrections when I was doing my work on incarceration there, to reform prisons in Haiti. He had been put in charge, as you know, of reforming Abu Ghraib in Iraq. In your book you talk a lot about the kind of plans that were taking place before the coup, but you don’t really talk in detail about your opinions of what happened then.

Jonathan M. Katz: Sure. The first thing to say is that the events happened long before I arrived—I guess, in the grand scheme of things, not that long since I moved there in 2007 at the end of that period of turmoil. You had the interim government, and then you had Réné Préval come into power, the UN peacekeeping mission was still doing its mop-up campaign in Cite Soleil and a couple of other areas against Aristide’s partisans. That story is important for understanding the earthquake because it’s such a prominent example of U.S. involvement, however you think the United States was involved— whether you think the Bush administration directly fomented the coup and moved directly to remove Aristide from power, or whether it was the way the Bush administration portrayed it, in which America was a kind of intermediary softening the blow and facilitating his exit.

There was a lot of reporting that was done in its wake that showed the involvement, through Stanley Lucas, of the International Republican Institute, which is, of course, headed by John McCain. If you go back to the reporting by [Walt Bogdanich and Jenny Nordberg at] the New York Times, and a couple of other sources, there seemed to be communication or training of some kind in the months and years immediately preceding it and there were longstanding relationships with a couple of the people who participated at a very high level in “the rebellion.”

CD: I was there in 1986 when Baby Doc Duvalier left on the U.S. Air Force cargo plane in transit to a five-star hotel in the French Alps. What’s striking about the two periods—and these repeated involvements between the U.S. government and Haiti—is that after the celebratory dechoukaj or uprooting, there was militarization, brutal attacks on Vodou, and the same kind of U.S. involvement. So there is a history to what we see now.

JK: Accountability and blame are very close cousins, and they’re words that are used to shut down or cover up one another, depending on how the conversation is started. So many conversations about Haiti—whether in a literary journal or at a high level panel discussion or a congressional committee, or even in the comments of an article on Yahoo or Reddit—so often devolve to ‘you were complaining about how things happen to have gone wrong, but its not our fault, it’s their fault.’

CD: There is a history to a number of the things that you write about. The differences between the Haiti of the 70s and and Baby Doc’s Haiti, on the one hand—and I’m not idealizing the Duvaliers by any means—and what went on during the interim government following Baby Doc’s departure are very striking. I don’t think we can ignore the various forms that occupation takes, and the similarities between what was happening in both of Aristide’s departures and during the American occupation from 1915 to 1934.

People always ask me, ‘Why would the United States want to do this? Why would they be so concerned about moving the peasants off the countryside, destroying all the Creole pigs, flooding the place with Miami rice, and so on?’ I do think that there has been an ongoing assault for years against the peasantry, and for me that’s aligned with the attacks on Vodou. You don’t write a great deal about what’s happening with Vodou, the new missionaries, etc., but there’s a way in which, over time, the destruction of the attachment to land, and to the lwa, the gods of Haiti, has a great deal to do with the kind of development that has been carried out—the so called ‘Taiwanization of Haiti’—which you write about. Rolph Troulliot used to say, and I paraphrase: the future of Haiti should be decided in the countryside, since the peasantry of Haiti has been holding Haiti on their backs for years. Do you want to speak a little bit now to your sense of why there’s resistance against going out into the countryside, working with the grassroots organizations, using Haitian expertise after the earthquake. You write about that refusal—the shocking non-involvement of groups that were already formed at the time of the earthquake, and instead using Clinton and his interim recovery group to decide what should be the future of Haiti. But I’m interested in your reflections on what you saw, how you thought, about the countryside and the peasantry.

JK: The way I approach any problem is to just try to figure out, ‘OK, what happened here?’ And one of the things that’s important for me to avoid as a journalist—a trap that journalists often fall into—is a kind of default balance, where you’re just trying to go through this supermarket of historical events, pull a couple of events off the shelves, and say, ‘This was the fault of the United States, and this was the fault of the U.N. and the international community, and these are some examples of the fault of the Haitian government, and these were the faults of the Haitian people,’ so that nobody can look at my basket and say that I’m being unfair, because I’ve grabbed a little bit from everyone. It’s just not a scientific or realistic way of understanding what’s going on.

The other thing that pops in there is the fact that it is so common—so easy—for so many of us, whether Haitian or American, to look at things through this lens of ‘us vs. them,’ that it’s almost impossible to talk about how these events have then unfolded, both over the course of Haiti’s history, and in the immediate period that I’m talking about after the earthquake.

So to answer more directly, about the peasantry and Haitian history and why we see the same patterns: I don’t really think, honestly, that there is a grand design that has been hatched, that is bound up in a dusty volume and keeps being pulled out over and over again in some room in Washington, saying ‘This is our conspiracy, this is what we’re going to do to turn Haiti into a finished product.’ If there was ever a moment when Haiti was an important question to U.S. foreign policy, it probably hasn’t been much since Thomas Jefferson’s administration, if it was even then. What I think that we’re encountering much more often is the fact that Haiti ends up, in most respects, being an afterthought, and that the people like Bill Clinton, maybe Cheryl Mills, who actually come down and put these ideas into practice, aren’t thinking hard about these questions that we’re asking about. So what ends up happening is that we just move to our default and put into practice the policies of the world as we see it. And the way the United States has envisioned development since at least the end of the nineteenth century—and if you’re really talking about development in terms of development in impoverished places, certainly since the end of the Second World War, and then in a major way in the last thirty years—has been that there is a set progression, a ladder of steps, which all societies must follow to get to modernity.

Do you believe when they call it the Haiti Hope Act, it’s not said with cynicism?

CD: But what about the flooding with Miami rice, the cooked-up threat of the swine flu epidemic that resulted in the killing of 13 million Creole black pigs—the only bank accounts of the peasantry? I’m going to push you a little bit here, because now you sound as if you are doing a balancing thing, and I’m going to sound more extreme. Although I don’t want to argue for a kind of Haitian exceptionalism, I think that Haiti is distinct from other so-called impoverished places. You have the Haitian Revolution—the only successful revolution of slaves and the first revolution in the New World—and you have a powerful alternative history that is in Vodou. When someone like David Brooks, after the earthquake, speaks about how Vodou is a progress-resistant practice that should be replaced with “middle class assumptions,” as he called it, that old story about barbarism helps to obscure the real causes of suffering in Haiti. I do think that there’s more to Vodou and Vodou practice than he allows. It is a philosophy, a discipline of mind, a way of being in the world that’s deeply connected to resistance. But just last year, Michel Martelly promulgated an amendment to the Haitian constitution that abrogated article 297 that officially removed the old prohibition against Vodou. It had been ratified by an overwhelming majority on March 29, 1987.

There’s a connection between things that might appear separate. The attacks on Vodou practice, desecration of temples and killing of priests can’t be separated from the vision of a new sanitized culture that the United States, Canada, and other places have for Haiti. That vision might seem to be well-meaning, an idea of what true modernity would look like. But for those of us who have lived and worked in Haiti, it’s something a bit more sinister: the deprivation of land goes hand-in-hand with the attacks on Vodou. I think there’s more here than getting everybody in the cities to work, which is our idea of a smart way to live—you know, work at way below minimum wage at various assembly industries. There is something about Haiti that cannot be ignored: it is the most black, the most African-based peasantry in the Caribbean. There’s a strong element of racism here, and a much larger attempt to destroy a unique, vibrant, and radical culture. Don’t you agree?

JK: There’s an enormous element of racism that goes into all these plans, and, as you put it, the general silencing of Haitian voices. Part of it has to do with a language barrier, which is so pronounced because there is this cultural and racial divide between the language of Haitian Creole and ‘western’ languages—[laughs] I don’t know what to call them. I hate referring to Haiti as something other than the West, because Haiti is so integrally part of the West, and has always been part of the West.

CD: That’s the great paradox. The earliest testing ground for capital, as well as being so African—

JK: There’s a constant discussion about the extent to which Haiti should be exceptionalized, and the extent to which it should be de-exceptionalized. It’s a huge issue. And I don’t think that I am just taking this up as a compromise position. Because another way to look at it is that Haiti has been a testing ground for so many of these ideas for such a long time. You know, Saint-Domingue was a great and exceptional center of slave capitalism that set a model for much of the rest of the world. A lot of the ideas that have infused American and European ideas of development have been formulated in Haiti—some of them during the [U.S.] occupation and some of them during the humanitarian programs that went on after the end of the Second World War. And that’s one of the major issues. People who are working in development, humanitarianism, UN peacekeeping, etc., can come in to Haiti and basically test any project out and see how it works. Then those ideas are taken from Haiti and put into other places. And after the earthquake, there obviously is a little of the reverse going on, where you see ideas that have been practiced in other places exported to Haiti. And then when it fails spectacularly, the attitude is, ‘Oh well, we tried this experiment and it didn’t work, let’s write a report and move on,’ and then nobody actually has to be responsible for the impacts it’s had on people’s lives. And you can’t talk about that without talking about race, and the intrinsic, different value that is often put on the lives of people who are darker skinned or look different, or speak a different language, or live in a different context than we do.

CD: But when people say, ‘This will be a better quality of life’ and they mean an industrial, plantation-style life will offer opportunities for the good life . . . Do you really believe that when they call it the Haiti Hope Act, which actually makes sure that the salaries of Haitian workers can never be raised, it’s not said with—I don’t know what the word would be—cynicism, I guess. Haiti Hope Act? All these great euphemisms for aid that further undermine the possibility of change.

JK: It is impossible to look at, for instance, the effects of the cholera epidemic and the blitheness with which the death of more than 8,000 people can be dismissed, and say that across the board the concern of all actors in Haiti is the betterment and preservation of Haitian life. Now I don’t subscribe to a notion—because I’ve never seen proof of it—that cholera was intentionally introduced in order to have some effect on a population or something like that. It appears to have been an accident. But nonetheless, it’s not being dealt with in a way that says the lives of 8,000 Haitians are equivalent to the lives of 8,000 Canadians or 8,000 Spaniards.

But that said—and I don’t mean to exempt myself from this—humans are very contradictory. I really do think that to a great extent the people who are coming in and implementing these plans probably do believe a lot of what they’re saying. I do get the impression, just from the way Bill Clinton talks—and I know that he is a very charming and effective speaker—that he thinks that building an industrial park and creating low-wage garment-stitching jobs really will create a better future for at least some segment of the population, which will then have this multiplicative effect that will spread.

CD: Let’s shift gears for just a minute. I thought your accounts of what happened to the aid, and the questions that you raised about why the aid never reached the camps was incisive: how responses after the earthquake were concentrated on Port au Prince and specifically Petionville. As a person who was on the ground and survived the earthquake, do you want to discuss what you think about the practice of humanitarian aid?

JK: I think the biggest problem that we keep coming back to is: What is the goal? When you look at the immediate aftermath of the earthquake—aid workers coming in, the search-and-rescue teams, the medical responses, and the fact that so much was concentrated in Port au Prince—the nebulous way in which it’s typically described is that they came to ‘save lives.’ But it’s never clear what that means. If the idea was to go all across the disaster zone with the priority of saving people that were trapped under rubble, the way to do that would have been to organize everybody, divide up the quake zone into different sectors, and make sure that you didn’t have aid all bunched in one spot. But instead what you saw were people coming and going wherever they pleased, and what ended up happening was that they all ended up in the same couple of spots. You could say two things about this: they were focusing on citadels of the rich and powerful and then, not coincidentally, those are the places that the news media tended to congregate as well.

The camps obviously prove to be very useful. They look very good in a TV spot or a short YouTube documentary.

CD: Exactly. You bring that up beautifully.

JK: And I think those things, in many ways, go back to the same roots. Foreign media come and go where the foreigners are trapped, and then foreign rescuers come and go where the foreign media are watching the foreigners who are trapped—and it’s being done for an audience overseas, because people in Haiti aren’t watching. And honestly, for the people who were trapped: I was a foreigner in the earthquake—I could have been easily been trapped under something—I would have been very grateful to have a foreign rescue team with foreign cameras coming in and pulling me out. Thank God it wasn’t necessary. But nonetheless it was very hard to watch these things and not feel that I was watching a television show, as opposed to a serious rescue effort. And there are a lot of reasons why you would put on a show like that. One of them is entertainment and viewership for CNN, and another is that the backers of these aid efforts, whose affirmation is ultimately necessary for the governments who are funding things like the urban search-and-rescue team, are the people who are sitting home in Chicago and Los Angeles watching this on TV. So it really makes sense to do it for their benefit, because if they’re not happy with the product, they’re going to stop giving money to it. And that’s something that we see writ much larger across humanitarian aid and development all across the board. It ultimately comes down to the people getting circulars in the mail, or seeing the TV commercial or Facebook updates. They want to feel good, they want to feel their money has gone to the right place, they want to get that little check mark of ‘mission accomplished’ in their mind when they get their update. And that backwards calculus is why these things often tend to be such spectacular failures. And so the question that you were asking before about people in rural Haiti versus urban Haiti—part of what happened is that over time these practices formed for many reasons. I think some of them have to do with the historical perspectives that we’re talking about, and some of them have to do with just larger development perspectives, and a very specific American and European idea of industrial progress.

CD: But you do say in the book, very strongly, that they strikingly didn’t consider moving the dispossessed and dislocated out of Port-au-Prince. Since there were so many people who went to the countryside after the earthquake, why didn’t these aid groups, these so-called humanitarian relief groups, go there to help? Many Haitians wanted to have farms. Isn’t it striking that no one went out to work in the rural areas instead of allowing history to repeat itself with everyone returning to Port au Prince.

JK: Again, we’re talking about a large range of actors, but it’s very clear from the ground that you had a bunch of aid workers and responders arrive who knew nothing about the country, didn’t speak the language, weren’t talking to people, and weren’t exposed to Haitians who could tell them what was going on.

CD: And that’s what most Haitians wanted. Many of the grassroots groups who were not involved in the planning were calling for decentralization.

JK: That’s absolutely so. The goal for years had clearly been to build up garment factories, rebuild the assembly sector and get as many Haitians as possible into those places, to sew as much as possible for as little money as possible. There’s really no doubt that this was the U.S. government’s strategy and the major U.S. investment strategy. Decentralization was very clearly an obstacle. And I think for many people working on the ground—Haiti is a kind of a sandbox for young development. For journalists, too—I’m including myself in this. I was very typical: in my late twenties I had had a little bit of success here and there working a couple different places, but Haiti was one of the first places where I could really come in, run the office on my own, and write stories that any portion of our readership were going to read. And then the idea was that I would work my way through Haiti, and—

CD: But you stayed longer than most [laughs].

JK: I stayed longer than most—part of the reason was the earthquake, and part of the reason was my appreciation of the country. Also, I’m the sort of journalist to dig deep into one place, you know, but perhaps the benefit came at far too high a price, for myself, more so than anybody else—but nonetheless I can’t ignore that. So I’m trying to include myself there. But it is absolutely true that there are people who have not been fully assimilated to the places they work, and they come in, see things on the ground, and actually do get a chance to talk to people, and sometimes they do turn around and say things that may percolate up the chain to the higher offices, that sometimes can result in changes in policy. However, many of the people who came in immediately after the earthquake were just disaster junkies. They’re usually not really caring, they’re just going in and trying to implement the plans that they’re trying to implement, and then they get out.

CD: That’s a great point that you made in the book. Your work is valuable because it refuses to participate in the kind of spectacle that presents Haiti and Haitians as abject, hopeless. You show again and again that, in a sense, humanitarian relief is more deadly than positive for the people it ostensibly comes to serve, because Haitians themselves know very well what to do for themselves and what their needs are—and its probably more than just plastic bottles of water.

I wanted to ask a question that is always on my mind when I go to Haiti. Would it be too exaggerated to argue that in some cases humanitarian relief is there to govern the displaced—not so much to help, but to manage them. Do you wonder sometimes, given the locations of the camps and their ongoing-ness whether humanitarian relief is a cover for a kind of stasis that enables the spectacle of disregard—not to put too heavy a point on it—to remain? I know that you’re not necessarily thinking in that direction in the book, but I wanted to know if you would speak to the usefulness of these large pockets of the dispossessed, living in conditions that are not only horrific but also pitiable. How does this perpetuate a certain image of Haiti?

JK: Within the limited parallax of the humanitarian world, and the humanitarian industry, specifically, the camps obviously prove to be very useful. They offer a very stark illustration. They look very good in a TV spot or a short YouTube documentary. They ended up being everybody’s illustration for everything. And this is true, by the way, even for critics of humanitarian aid—it was a very easy place to go and film and show the desperation that these people were living in. In Haiti, one of the first things that people always come to—and that even I resort to—is just that number, which is basically a fictive number, of how many people are estimated at that given moment, to be living in the camps. And it’s almost always explained as ‘still living in the camps.’

Whenever foreign, and particularly American officials talk about Haiti, there is this constant sense of contagion.

CD: Only a month after the earthquake the GEO group, formerly Wackenhut Corrections Corporation, received a contract in Haiti through the Department of Homeland Security for guard services. So prisons were the first thing to be built. Many Haitians I’ve talked to, certainly in the countryside, wonder about talk by the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) of ‘stabilization,’ when nothing needs to be stabilized. Many people fear that the camps, and keeping people in the camps, is a way to have a ready labor force, and people, especially those who are older, fear what might happen if you refuse to labor. During the American occupation if you refused to labor to build roads, you were killed or imprisoned. And I think people still have in their minds this choice: labor or prison. Did you see evidence of prisons being built (which is a particularly U.S. mode of development)? After all, many correctional officers from different countries—even China—went to Haiti as early as the 2004 flood in Gonaives.

JK: By the way, there there was recently a prison-construction program announced that is funded in part by the U.S. government, and the women’s prison is going to include a small textile operation and a vocational training center.

But more importantly, there really is an inherent contradiction in the major conversations about Haiti. On the one hand there’s all this talk about development, but on the other hand there’s all this talk about stability. Stability suggests sameness, a perpetuation of the static form. You don’t want things to change too much, but then at the same time you’re saying, well, things have to change, because they’re going to develop. Obviously if things are going to develop, you can’t know exactly what they’re going to change into—it’s inherently unstable. Despite the contradiction, there seems to be a desire there to have both of them at once. You see it in this country as well: people who want to cure poverty but are afraid of income redistribution, who want to help the poor but don’t want them to have stuff that currently belongs to the rich.

CD: And they don’t want to leave outlets for resistance—any possibility of people getting together to make change. That’s the most disappointing thing in watching, over the years since Baby Doc left, these repeated moments of tremendous excitement in the vast majority who want change. Then they watch as the means of their salvation turn into the means for the very stasis that we’ve been speaking about. Thomas Jefferson once wrote about ‘receptacles for that race of men,’ and as you were speaking, I was thinking about all these receptacles where people are held—if not in prison, then they’re in the camps. It’s very striking to me, just on the ground, spatially, when you go to Haiti now.

JK: I think there’s definitely an element of that. Look, there are clear contradictions running through all these things. You have groups that want to get people out of the camps but those groups need the camps. You have people who want development but also want stability. You have aid groups that promise to work themselves out of a job, but don’t want to work themselves out of a job, because they want to keep their job. So the question is whether the contradictions are part of a grand design, in which people have a secret and explicit goal, or whether people are operating merely on these contradictory levels. I continue to think that, to a great extent in the aggregate, and even often times on an individual level, it’s really these contradictions that are just unexplored—that people want change, but they don’t want things to change too much; they want to implement solutions, but they don’t really care if the people upon whom they’re imposing these solutions are going to benefit from them. I’m still a little more disposed to thinking that these things are just coming out in the wash, rather than coming from widespread mendacity.

CD: No, but I think that our government does perceive Haitians in incredibly negative ways. Do you recall the scandal about blood stigma, and the incarceration of Haitian men, women, and children at Guantanamo in the ‘90s, out of fear that they were carriers of tainted blood, that they were causing AIDS? I agree with you that this is not, on everyone’s part, a grand plan, but I do think that the treatment of Haitians by the United States has been deplorable. The New York Times ran an editorial at the time called “Blood Stigma, Blood Risk” that supported the U.S. Food and Drug Adminisration’s policy of excluding Haitians from donating blood, despite an FDA advisory panel’s advice to lift the ban So going hand-in-hand with this view of development and stability is this remarkable racism against Haitians—a tendency to portray them in the worst manner possible.

JK: I agree. There is this constant sense, whenever foreign, and particularly American officials talk about Haiti, that what we're taking about is contagion. If you look even at the donors’ conference after the earthquake [at the United Nations in March 2010], they talked in terms of carrots and sticks. The stick that Hilary Clinton was using to explain why it was so important to give money at that donors’ conference and invest in Haiti was all about contagion: Haiti is going to spread unrest, disease, or some kind of contagious economic failure throughout the hemisphere. And on the carrot side of the equation, she actually tried to give the optimist’s version of that same idea, in which Haiti would develop and spread the good contagion of prosperity and wealth throughout the hemisphere, and become an example.

Consider the ‘four Hs.’ At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, in 1983, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned that this new disease was being spread by ‘Haitians, hemophiliacs, heroin addicts, and homosexuals..’ That declaration came 30 years before the cholera epidemic in Haiti, yes. Still, there seemed to be no contradiction in the minds of the CDC itself saying they didn’t want to play the blame game, a mere generation after tainting the reputation of the Haitian people without end for being originators of a disease that they did not originate, and probably did not even carry into this country. I think that’s hugely important, obvious, and really undeniable. I’m not saying that Hilary Clinton personally is self-consciously being racist when she says things like this, but I think there is a sense of dirtiness, of otherness, of threat. And some of it is definitely political. It certainly was political in the years leading up to 2004, with rumors that that Haiti was spiraling out of control. As a result $500 billion dollars of aid that was promised was withheld. And whoever was paying for the coup spread the word that something bad was going to happen, that the whole thing was going to fall apart, and was going to create this black hole of violence and chaos—no pun intended—that it was going to suck in everything around it, or that this contagion was going to spread throughout the hemisphere.

CD: Exactly. I thought one of the most fascinating characters in the book is Préval and his alternating reticence and rage. I’m wondering what you make of his involvement, or non-involvement. What would have happened if Jude Célestin—the government-backed candidate—had been allowed to stay during the election.?

JK: I’m glad you read it that way. I agree, I think Préval is a fascinating character, both historically and as an individual—

CD: He’s a supreme example in your book of sustained ambivalence that’s orchestrated again and again.

JK: Even before the earthquake, he would accept Clinton in a special envoy and then sort of undercut him at every turn. He would go to the investment conference—God, I still remember that—and after Clinton gives this huge, boosterish, almost evangelical speech about the importance of foreign investment, Préval then just gets up and pours cold water all over everything, and says something like, ‘Well, we really need to talk about how Haiti remains a trans-shipment point for South American cocaine, and as long as we’re under the thumb of the drug cartels this is not a good place to invest.’

CD: His statement about ritual, the one that you write about, is haunting: “I am worried, because I dread that once this first wave of solidarity and human compassion has dried up, we will be left, as always, alone but truly alone, to deal with new catastrophes and to see restarted, as if in a ritual, the same exercises of mobilization.” There’s this kind of repetition compulsion, history repeating itself.

JK: One of the things that makes Préval such a tragic figure is that he can see and articulate what is happening but he’s powerless to stop it. I think as a journalist, I can see myself and a lot of my colleagues in that as well. We’re often doing the same thing. We’re describing what’s happening, and we’re seeing it happening as it happens, but there’s nothing that we can do.